08-19-2020 - Case Study

Breaking Down the Script - Part 1 - Locations

By:

No cinematographer can simply walk onto a set and succeed. Instead, it can be argued that their most important work is done in the pre-production, both in consultation with the director and in specific preparation for their own responsibilities. The director will lay out their intentions and ambitions for the whole film. The cinematographer then has to work out how to use the unique visual language of motion pictures to support that vision. For me, this process begins with breaking down the film, doing a scene by scene analysis, and determining how I will use the camera and lighting to achieve what the director wants.

But first. The location scout.

Much of breaking down the film is done in the cinematographer's head and on paper. Before that process starts, there is a discussion of potential shooting locations followed by several location scouts, led by the location manager and eventually joined by key department heads and the cinematographer.

Often a cinematographer will reject a location before a scout based on photographs. It's far better for the cinematographer to be forthcoming at this early stage and save the rest of the team valuable time.

Sometimes locations are rejected once they are scouted. I always look for certain key things when determining whether a place is suitable or not. If those things aren't there, I discourage production from selecting that location. That is if the shoot should even be on location.

One of the first things I consider is whether a scene would be better on a studio stage. Some think studios are prohibitively expensive. I don't believe this is always the case. Although a studio build can be costly, producers sometimes miss the later savings that studio shoots accord a production. There are a few things they should think about; studio shoots are very efficient. Studio shoots allow a production team to get more shots, in an atmosphere that is conducive to better performances and in less time. Why? For one thing, studio sets have walls that are made to be moved and removed, which means heavy equipment, lights, and set dressing can be quickly loaded in and out. Additionally, the placement of the camera is much simpler. On location, camera crews sometimes have to squeeze themselves into the corner of a small room as there is no place else to go and still might not get the angle they want.

Lighting is also much easier on stage, not only because walls can be moved but because the sets don't have ceilings or have ceilings that can be moved. Additionally, a studio set up can be rigged and left up over several days of shooting. Sometimes on locations, all the equipment has to be "struck" for safety reasons and re-rigged the next day. There are additional things that make studio shoots easier, like the ease of parking, the proximity of additional equipment, existing makeup and hair facilities, the proximity of the production office, and many other things designed to maximize efficiency.

Of course, the decision about whether to shoot on a stage or on location is not entirely the cinematographer's. The director may feel that location contributes a particular "feel" or visual patina that can't be achieved on a stage. Producers may decide that though a studio shoot is efficient, the initial outlay is just too great. These are the decisions they have to make. It is the cinematographer's job to provide the key technical data and explain the creative impact of a studio or location shoot and then leave it up to the producers and director to make their decisions. Certainly, if there are a great many effects, like wire-work and green-screen, everyone will probably agree a stage shoot is the best choice.

If a location is selected, one of the first things I look at is the surrounding environment, as that will determine the success of a location shoot. I know, for example, that if the position of the location means vehicles are forced to park a long distance away, that will slow down shooting. It will mean that every time I have to bring another piece of equipment onto the set, I will have to wait for a technician to go to where the trucks are parked and then bring it back. There might be a hundred such trips in a day, and doing a simple exponential calculation, you can see how much shooting time will be lost.

On first scouting a location, I will also be looking for where I can place lights. Even if we are shooting interiors, the lights I decide to use may come from outside the windows of the location, replicating sunlight, or streetlights, or moonlight. If I have a big location and I want to use big lights, like the huge truck-mounted sources that use giant telescoping arms, like Musco Lights, then the nearness of power lines and trees might limit where I can place these fixtures. I also have to consider if neighborhoods where we shoot have strict curfews, particularly if we are doing night shoots. Even with day shoots, an early curfew on exterior lighting and crew noise effectively shortens the shooting day and makes it harder for the cinematographer and the creative team to get the shots that are necessary. With night shoots, you might sometimes get complaints from people who have homes near the shoot about lights shining through their windows. If those people haven't signed off on shooting permits or if a local ordinance empowers them, they can shut down an entire shoot. Locations on airplane flight paths are also a nightmare. Although it's not directly in the cinematographer's purview, if the sound recordist has to stop a take several times because of air-traffic, it impacts the entire production. It will slow down shooting and may prevent the director from getting all the shots they require.

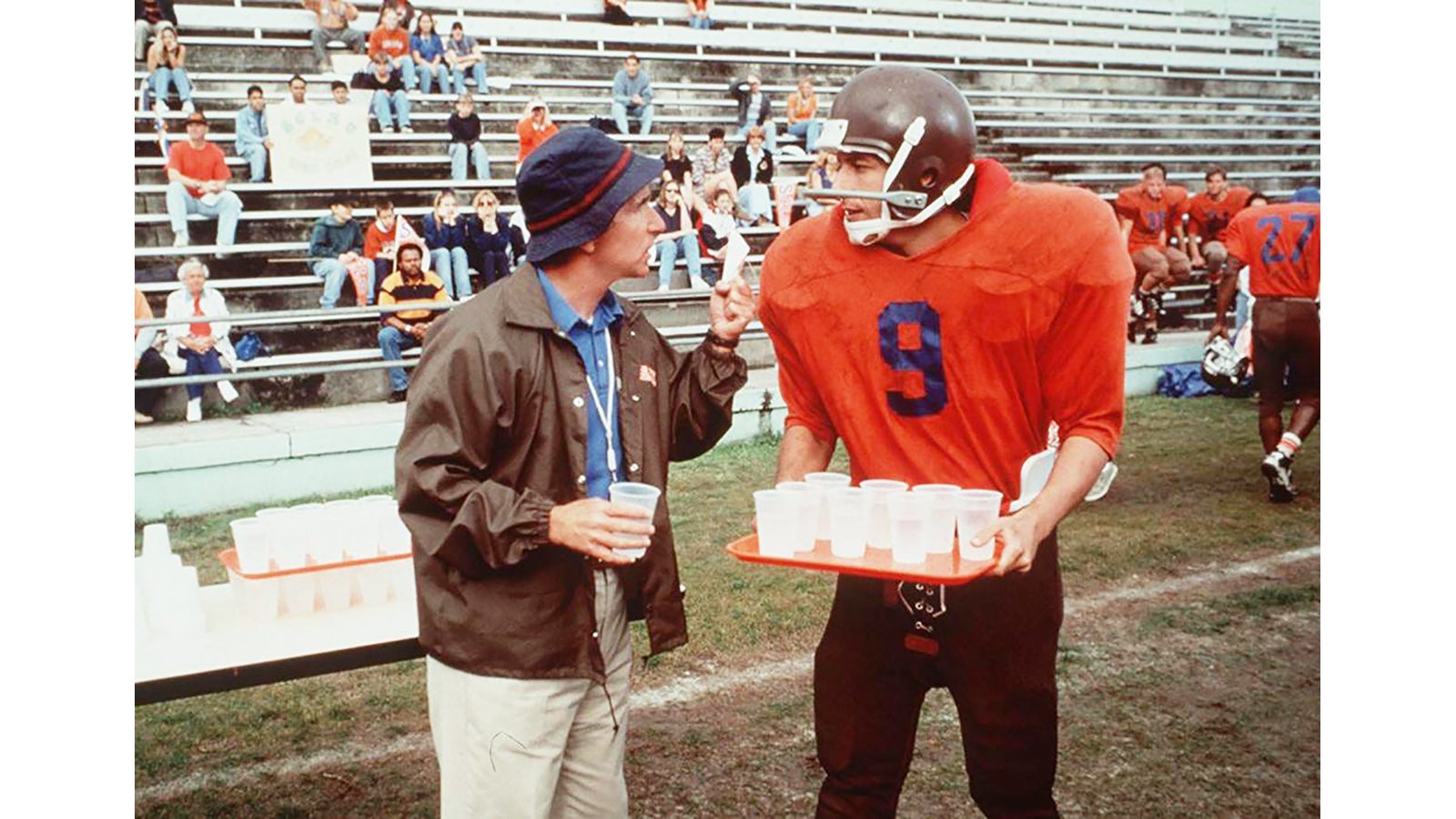

If the shoot is at an exterior location, the position of the sun will be very important to the cinematographer as it will determine where shadows will fall. Also, if a location is surrounded by high buildings or hills, they can block the afternoon sun and shorten the effective shooting day. The middle of the day can also be a problem. No cinematographer likes hard sunlight, particularly when it's directly overhead as it is in the middle of the day; it makes for very unattractive shadows on the actors' faces. In these circumstances and when a film's budget is big enough, cinematographers like to hang "fly-swatters", which are very large diffusion mediums mounted on frames and supported by crane arms. Once rigged and the frame is sent aloft, they shade the entire shooting area. They make a big difference but are heavy, so soft wet ground can be a problem. The ground can be damaged, and the crane can be unstable. When I shot the film "The Waterboy", much of the football material was shot at the Orange Bowl stadium in Florida. To protect the field, we had to lay down boards to put under the fly-swatter's cranes and also our Musco lights. It had rained the day before, and it was difficult to move these pieces of equipment without damaging the expensive field. Additionally, because the walls of the Orange Bowl shaded the field in the afternoon and in the morning, my shooting day was short. I had to bring in additional light sources, and light from many sides through heavy diffusion material to create artificial daylight, which I extended into the afternoon and on one occasion, even late into the night. The Orange Bowl was a magnificent location, and it was the best place to shoot, but I had to do a lengthy analysis as part of my script breakdown to make sure I had all the pieces of equipment I needed to make it work, and that it achieved the director's stated intentions, that it worked creatively and it worked economically.

When walking into an interior location, I look for different things. The first thing I look at is the ceiling height. Low ceilings are the bane of all cinematographers, and though a location with a low ceiling may seem right to the director, it won't seem right to them when the lights are rigged and end up only a few inches above the heads of the actors. I also look to see the overall size of the set. I want a set to be bigger than it is meant to appear on-screen. A thing I will say to a director and to producers is it's always easier to take a big location and make it seem small. It's impossible to make a small location, big. To make a set seem smaller on camera is a simple trick; you only shoot part of the space, and it's a trick cinematographers like to employ because it's hard to shoot in a small location. There are a variety of reasons for this; First of all, depending upon the lights you’re using, film lights can be hot, and the many bodies of the crew causes a further build up of heat. This causes actors to perspire, which slows production down as it requires wardrobe changes and make-up fixes. Additionally, crews don't work efficiently in heat. They grow exhausted and often irritable. A small location also limits the amount of camera movement that a cinematographer has. A dolly takes space, and if there isn't room for one, a camera can't be moved as might be desired. A small location also limits camera placement. Solid walls can't be moved. Most cameras are pretty big once fully set up. Actors have to be a fair distance away to shoot them in a medium or a wide shot. So on small sets in small locations, cinematographers sometimes find themselves shooting from an angle that is available rather than the angle that allows the best composition.

Confined space also limits how much the actors can move, which means that their ability to give their best performances can also be limited. Some actors like to use their bodies and their movement to express themselves. It's harder for them when they can't, and they can find small locations limiting.

It is sometimes very difficult to convince a first time director that a location that seems exactly like the one they envisioned won't shoot the way it looks. It is incumbent on the cinematographer to give them that information.

Also, in my script breakdown, I will consider whether a location needs a pre-rig. Pre-rigging lights mean the shooting day can be dedicated to getting the best performance rather than lighting and preparation. Sometimes producers don't want to pay for a rigging day. In planning, there is a lot of emphasis on paper savings. Paper savings presume all will go well once shooting begins. But things rarely go as smoothly as everyone hopes and saving money by cutting a pre-rig, can cost much more in overtime when the shooting day doesn't finish on time.

Another part of my breakdown is the equipment order. I will carry a certain amount of equipment in the lighting, grip, and camera trucks, and this gear will work for most of the shooting. My lists are fairly standardized, but the location scouting will cause me to modify them slightly, as will my discussions with the director. If I understand their vision, I will know which equipment will best suit their needs. But, every film has certain days when more equipment or special equipment is required. A cinematographer has to determine that in the pre-production, to see if the budget will allow the expenditure and to give the production office ample time to book the special gear and the additional crew needed to operate it. This requires a lot of planning.

A good size location shoot is a very big deal. When I was shooting the second unit on "S.W.A.T." we took over whole city streets. The crew was many hundreds of people. There were many trucks, additional lights, generators, cameras, and rigging equipment, as well as extras. On one set up, we had 18 cameras and crews. But we needed them. You have to be sure to have enough equipment to move quickly without breaking the budget, and you have to have the right gear to get the shots you need. The sequence with all those cameras was an action sequence, and when I saw the cut, I saw the editor had used every camera set up.

Once the locations are selected and the decision is made about which sequences will be shot on stage and which on location and once I have prepared a preliminary equipment list, I then focus on the creative visual breakdown of the script.

About the author:

Steven Bernstein, DGA, ASC, WGA is an ASC outstanding achievement nominee for the TV series Magic City. He shot the Oscar winning film “Monster,” “Kicking and Screaming,” directed by Noah Baumbach, “White Chicks” and some 50 other features and television shows. The second film he wrote and directed, “Last Call,” stars John Malkovich, Rhys Ifans, Rodrigo Santoro, Zosia Mamet, Tony Hale, Romola Garai and Phil Ettinger, is scheduled for release later this year.

Steven can be followed at Stevenbernsteindirectorwriter on instagram where he regularly posts short insights and illustrations about filmmaking.