08-26-2020 - Case Study

Breaking Down the Script - Part 2 - The Creative Breakdown

By:

When I begin the creative breakdown, I first make a diagram with each scene from the script and two main column groups; "camera" and "lighting." "Camera" has several subheadings; "camera movement," "camera mounts," "camera lenses and multiple cameras," "filters" and "composition." Under "lighting," I have "the quality of the light,” "lighting color," "lighting texture and movement," and "highlights and shadows."

What do all these categories mean? If you see them principally as technical subjects, then you are missing an opportunity. I prefer to see each of these categories as a specific type of film language that works the way all languages do. I borrow terms from the academic study of language, semiology. I break language down into two parts. The sign (that which the audience sees) and the meaning (the idea the sign conveys). The terms semiology uses are signifier (the visual "word") and the signified (again, the meaning or the idea). So, for example, you place a camera at a low angle, looking up at an antagonist. The low angle is the signifier. The signified is that the antagonist is powerful and dangerous. Visual language is less specific than spoken language but can be more emotive; the way poetry is emotive in part because it isn't specific. Poetry, like cinematographic images, can have many and varied meanings.

If you look at all the categories I list above, it is useful to break them into sign and meaning, signifier and signified. What images or parts of images create what meanings? By undertaking this process, you will create a visual script, a series of images, camera choices, and lighting choices that create meanings, thoughts, and feelings in the hearts and minds of the audience. This is the realm of visual language and of the cinematographer.

All photos: Jeff Berlin

Camera movement

Everything in the breakdown begins with intention. Nothing in the DP's decision making processes should be arbitrary. Because of the speed at which television is sometimes shot, often all the dialogue will be covered with a master wide shot and a couple of singles or close-ups. This isn't very creative, and it's not ideal. It tells the story, but it contributes little artistically. It's like describing an oil painting by a master. You can explain with words what is going on in the frame, but it rises to the level of art when one actually sees it - a unique vision created by a unique sensibility. I would hope this is what most cinematographers aspire to - a vision in the service of the director's intentions.

It would be impossible to list here the many and varied techniques available with the camera to elicit reactions in an audience. That is not my intention. Rather I am proposing a way of thinking for a cinematographer that is applicable to all films and will lead to greater artistry from which techniques will organically grow.

With this in mind, Consider some types of camera movements. One of my favorites is the small push in towards a subject with the camera mounted on a dolly. This movement might only be a few inches and barely perceivable, but it can elegantly emphasize a key dramatic moment or a line spoken by an actor. It's like gently increasing the volume of an amplifier. The audience simply feels a greater emotional intensity, but they don't know why. As I break down a script, I look for key moments that might benefit from this simple movement, one of many I might choose.

At the other end of the spectrum, there is the crane shot. Think of how you respond to a view from a mountain top or an airplane. It's very different from seeing the world at eye level. You might contemplate the grandeur of the landscape beneath you. This is more dramatic when this perspective is gradually revealed. The crane shot can do just that. A crane shot might start on the close-up of a face or an object and then rise to gradually reveal a sublime landscape. In this instance, the audience could make a connection between whatever is in the close-up and the grand expanse of the camera's final position. Might it suggest a character's vulnerability? Might it suggest the indifference of nature to the fate of an individual, as in a Terrence Malick film? Absolutely. Possibly. Again I cannot provide a lexicon here of every type of shot, but rather the thinking behind the creation of shots.

There are many agreed orthodoxies that suggest certain camera movements produce certain reactions in an audience, but they are not absolute and can often depend on context and other synergetic elements like performance, music, and production design. But my point here is that cinematographers should be thinking about what they believe the reaction of the audience will be to camera movements. That belief can be based on their experience, their experience of watching films, and their intuition. It should never be arbitrary because every camera movement is laden with meanings. The meaning will be either one the cinematographer chooses or one they choose not to control.

Camera mounts

Related to camera movement is how we mount the camera. Even this decision creates a language that speaks to the audience. For example, a camera mounted on a heavy dolly which rolls on a double plywood floor laid down by the grips will create a movement virtually imperceivable to an audience, which might suggest an interior emotion. On the other hand, a handheld camera has a lot of shake and movement, which might suggest a character's subjective point of view. It is also associated with the way documentaries are shot, so when used in a drama, it can suggest the events portrayed on screen are "real."

The Steadicam is something between the dolly and the handheld. Its movement can suggest either a point of view or act as an objective camera position, not unlike a dolly but with a little less stability but greater flexibility.

Another mount is the stabilization head, which stabilizes shots using gyroscopes or tuning forks. A stabilization head on a high-speed vehicle can excite an audience. If mounted on the front of a vehicle, it can create a feeling of terror in an audience.

What should be noted with each of these examples of camera mounts is that none of them are scripted. They create feelings and reactions in an audience, but the choices the director and cinematographer make aren't referenced in the screenplay. The use of the camera can place ideas in the unconscious mind of the audience without using dialogue or story. They come from a different script, a visual script created by the cinematographer, which begins with the process of the breaking down of the script.

Camera-lenses and multiple cameras

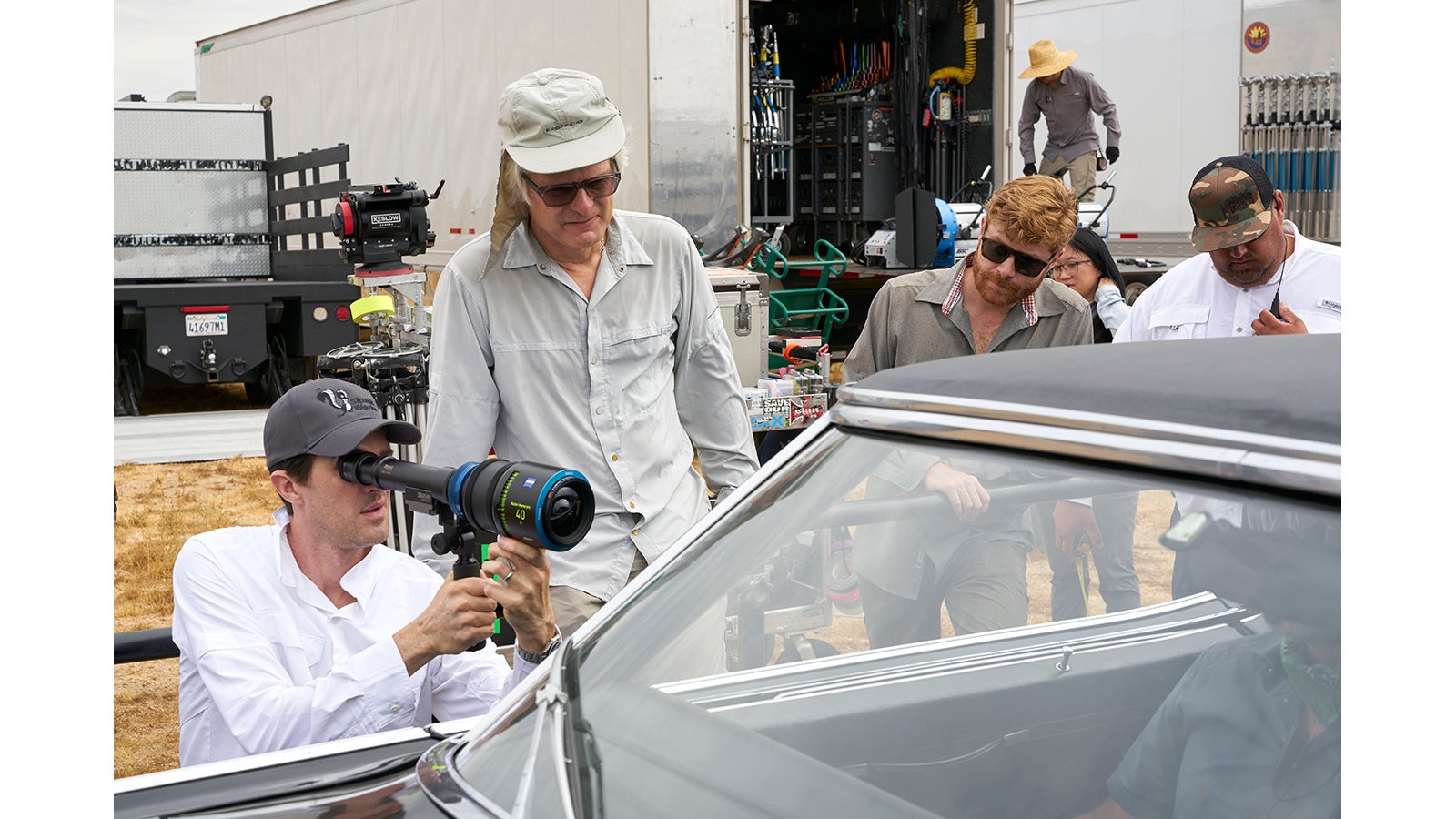

A cinematographer's day begins with a scene blocking; the actors and the director working to determine the actors' physical movements and final placements.

During a scene blocking on the shooting day, most cinematographers use a director's finder. This device allows it's user to see potential shots through a lens. The cinematographer will use this to find the best compositions. Choosing shots is usually done with the actors and on a fully constructed set. But a cinematographer in thinking about a scene beforehand can anticipate a lens choice or make a general creative decision about a stylistic preference. For example, a long focal length lens (telephoto lens) creates a shallow depth of field. This is painterly, and some think attractive; others think that it is unnatural. It's a choice. Also, in action sequences or sequences with a lot of movement, the shallow depth of field of long lenses doesn't allow clarity of image at different distances, which can be limiting. Long lenses are also difficult to use when the camera is moving as they amplify shake and vibration.

The opposite of the telephoto lens is the wide-angle lens. The wide-angle has a deep depth of field but can cause distortion when close to a subject. The wide-angle can be great for action and can incorporate complex compositional elements that long lenses can't. They are also great for moving and handheld cameras in that they minimize shake and vibration.

As I mentioned earlier, the script breakdown is not only about creative decision making. It's also the time to start considering special equipment orders. Cinematographers will carry a package of lenses during the shoot, usually a mixture of a couple of zoom lenses and a set of prime lenses of various focal lengths, which will include both wide-angle and telephoto lenses. But in addition to those standard lenses, sometimes extra-long focal length lenses are needed for certain sequences, or special close-up macro lenses, or extreme wide-angle lenses. These have to be ordered for particular shooting days via the production department.

One of the things a cinematographer will consider while doing the script breakdown is when and where multiple cameras will be advantageous, and then also place orders for them with the production department. Action sequences, for example, might be best shot with many cameras; five or six or more if production can afford it. I generally like to carry at least two cameras all the time, but some directors insist on only shooting with one as it allows them to focus more intensely on performance.

The choice of lens manufacturers is another part of the script breakdown. Each set of lenses manufactured by different companies has particular characteristics, which means they vary in contrast, color bias, sharpness, etc. Different cinematographers like different lens manufacturers, sometimes citing the way they render skin tones, highlights, or shadows. But sometimes they will choose lenses specifically for a film. Gabriel Beristain, BSC ASC, did something even more radical. On the TV series "Magic City", on which I also worked, he asked the lens rental company to remove the coating on a few sets of lenses. That "anti-halation" coating eliminates lens flare, but Gabriel wanted that flare so the lenses would resemble the quality of 1960's lenses. It worked spectacularly and was one of the things that contributed to my Outstanding Achievement nomination from the American Society of Cinematographers. Gabriel's choice went to the unscripted script, the visual treatment that cinematographers create during the script breakdown.

Some cinematographers like to use zooms extensively. Zooms are rarely as sharp as prime lenses, but they can allow for speedier set-ups as it's just a matter of rotating the lens barrel rather than having to change the entire lens. If a shooting schedule is tight, using zoom lenses is a decision a DP might make while breaking the script down. Other cinematographers believe the quality of the image is paramount and will only use primes. I fall someplace in between. On some productions where speed will produce greater quality because we can get more shots, I will make strategic use of the zooms. But on films for the big screen where quality matters most of all, I prefer primes from my preferred manufacturers.

Follow this link for Part 1 of this article: Breaking Down the Script - Part 1 - Locations

About the author:

Steven Bernstein, DGA, ASC, WGA is an ASC outstanding achievement nominee for the TV series Magic City. He shot the Oscar winning film “Monster,” “Kicking and Screaming,” directed by Noah Baumbach, “White Chicks” and some 50 other features and television shows. The second film he wrote and directed, “Last Call,” stars John Malkovich, Rhys Ifans, Rodrigo Santoro, Zosia Mamet, Tony Hale, Romola Garai and Phil Ettinger, is scheduled for release later this year.

Steven can be followed at Stevenbernsteindirectorwriter on instagram where he regularly posts short insights and illustrations about filmmaking.