11-05-2020 - Case Study

The DP and Story – Part 1 of a Film Theory Series with Dan Kneece

By:

Dan Kneece has spent years creating amazing images. He started filming motion pictures at age 13 when his mother bought a Super 8 camera. In 1979, while finishing his Master’s in Media Arts at the University of South Carolina, Dan began his professional career shooting news at WIS-TV in Columbia, SC.

Soon thereafter he was taught Steadicam by inventor Garrett Brown which led to a 28 year career as a Steadicam Operator and an ongoing professional relationship with Director David Lynch on films such as Blue Velvet, Wild at Heart and Mulholland Drive. For many years, Dan was an “A” Camera Operator on major film, television, commercial and music video productions. He has worked with the best in the business and learned from them all. He now uses his knowledge, extensive filmmaking experience, and incredible eye to excel in his work as Director of Photography.

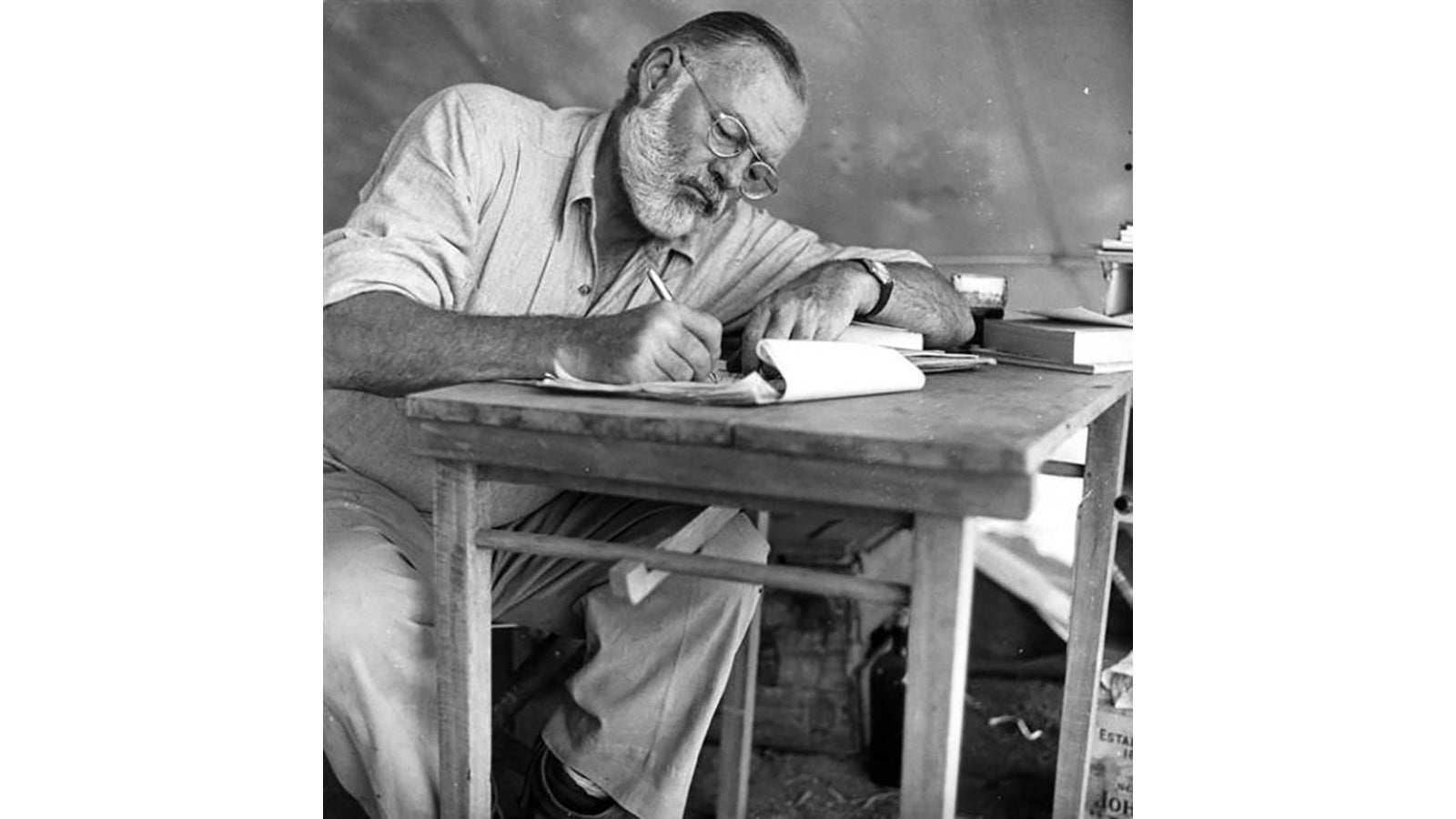

Ernest Hemingway

Where do stories come from and how are they conveyed to others? Stories come from ideas. Be they ideas sparked from an actual event or something fabricated the beginning is always a moment in someone’s mind thought worthy of further examination.

Ernest Hemingway knew this. Being a newspaper man, he always reduced his ideas to the simplest form so that all might understand them. Hemingway even employed devices to convey his ideas to the reader.

In his book, Ernest Hemingway on Writing, Hemingway had a conversation between his younger and older selves. His older self is Your Correspondent or Y.C. His younger self is simply referred to as Mice. One quote that comes to mind is, “Mice: What is the best early training for a writer?” “Y.C.: An unhappy childhood.”

Why is this quote so important? It is because of what it implies. Hemingway is saying that to write a story you must have experiences worth conveying. Otherwise why bother? Even invented stories must have some basis in fact. Even fantasies must have some anchor in reality. Otherwise they are un-relatable by the intended audience. As humans, since we are the target group, there are certain things we know to be true to make our world habitable.

In books this world has no bounds as anything imagined can be conveyed with words, but in the cinema we only have visual and auditory clues to share our story with the audience. Whereas in books we can examine the inner mind of our characters, movies mostly rely on what can be shown or heard. The inner workings of the mind are mostly a mystery in films and the use of narration to convey this is usually seen as the folly of a director in trouble.

So where does this leave us when our goal is to tell a story through the lens? We use our devices and tricks to convince the audience they are seeing something they actually are not, conveyed by the elusive “Movie Magic”.

“Movie Magic” brings us back once again to the idea. An intangible formed in someone’s creative mind and allowed to ferment until it is eventually jotted down, pen to paper. Maybe it’s just a word or a few words at first, and it can come from anyone at any time. No matter who creates it, expansion is necessary into treatment and finally script so other creatives can access it in a tangible form and in turn, perform their own magic. This is the beginning of the film.

At this point, the work can begin in earnest. Breakdowns are done. Cast members are considered. Key crew selected. Mock-ups are made. Locations are selected. This film, in its infancy, begins to take shape.

During this time the director and director of photography find moments to spend together, discuss ideas, share references, and decide on a style and look as they move forward.

This is a key moment in director/DP interaction and is a formative time in what is to become a very intense relationship. Not intense in a negative way, but intense as in a meeting of the minds, a mental lock, a unified focus, a mutual respect and a deep trust that must never be broken.

This is when we truly learn what film is being made. We learn the director’s vision, a vision that also must become ours for if the project is to succeed, there is one thing certain, everyone must be making the same movie.

At this point the DP can begin his or her planning. He or she now knows the director’s vision so they can take the script and begin to imagine the story visually. He or she knows the script is the basis of a film just as concrete forms the foundation of a house. With bad foundations houses fall down. With bad scripts, so do films.

In filmmaking, everything comes down to story. Sometimes a great director and cast can save a marginal script, but more times than not story is key, so it is critical to start with the best script possible. The bonus will be that everything you need to know will be in that script. Every moment, every mood, every transition is spelled out.

At this point location scouts become invaluable because you actually get to see the physical spaces where the story will be brought to life, and you can now also start to feel the mood of what is to come and how you might achieve it. You will see the strengths and challenges of each space and formulate how you might approach them with the tools in your arsenal as DP.

That said, unless you have something very specific in mind, it can be difficult to pick what tool to use this far in advance. Lighting-wise yes, because lighting fits within the mood of the scene, but a particular camera conveyance probably not. You might know if you want an extremely long pullback to slowly reveal a set per the director, but still you are taking baby steps at this point.

If you’re on a film large enough to afford storyboards, those can be used as a reference when they are available, but those are just ideas of what something might look like and on most jobs are not to be taken as gospel.

The more time you spend with the director the better at this point as both of you are still allowing the concept to gel in your minds, and this is the time you, as DP, can provide invaluable counsel to your director; not in trying to sway the direction of the film, but in gathering little nuggets of wisdom as to how the director’s film will proceed.

All this time you are formulating your plan of how you can assist the director in achieving the film he or she hopes for while being true to the script and story. Start thinking now of how your work might enhance the film.

At this point you should know which of the three types of director you are working with: the actor’s director, the technical director or, the best of both worlds, the well-rounded director.

The actor’s director is mainly concerned with the actors and wants nothing to do with your little bag of voodoo. This director is all about actors and performances. He or she is happy to leave all that is technical up to you. Anything that is not an actor is under your purview.

The technical director wants to control the mechanics of the film. The actors are meat puppets to him and are meant to do as they are told. You are there to also do as you are told and to save these technical directors from themselves as you convince them what saves them is entirely their idea. While some are quite good, many have very high, often unwarranted, opinions of themselves, they must be allowed to flourish until just before they crash and burn in glorious hellfire. Your job as DP is to help them go right to the edge of their creativity without letting them drag you and the entire crew over the edge of the precipice.

Working with the well-rounded director is one of the greatest joys of the film business. They come in prepared, but are also willing to improvise. They know actors and how to guide them into their best performances. They know how to communicate with the crew to get their best as well, and they value their DP as a trusted collaborator whose only goal is to help them succeed.

The key to working with any director, and this is true for actors too, is to inspire confidence. You want to inspire their confidence in you, of course, but you also want to inspire them to have confidence in themselves even though you know, as the late Ted Churchill put it, on the inside they are “Shivering like a Chihuahua passing a peach pit.” Directing and acting are two very scary places to be and as I’ve said many times before; my job as DP is 2% what they hire me to do and 98% babysitting.

The importance of people skills cannot be overemphasized. You must provide a safe place for the actors to act and the director to direct. Directors have more on their minds than a hundred humans and actors expose their inner psyche so deeply they feel like they are skinned alive and covered with salt. Both require the utmost care to reach their full potential and minimal physical awareness of the technical greatly helps this process.

My late father told me on more than one occasion, “A good child is seen and not heard.” When younger this annoyed me greatly, but on sets it proved invaluable advice. The ability to be on set and not utter a sound is a great asset; invaluable really, that affords those who need to be able to think the opportunity to do so. Actors and directors need this space. They are the thinkers.

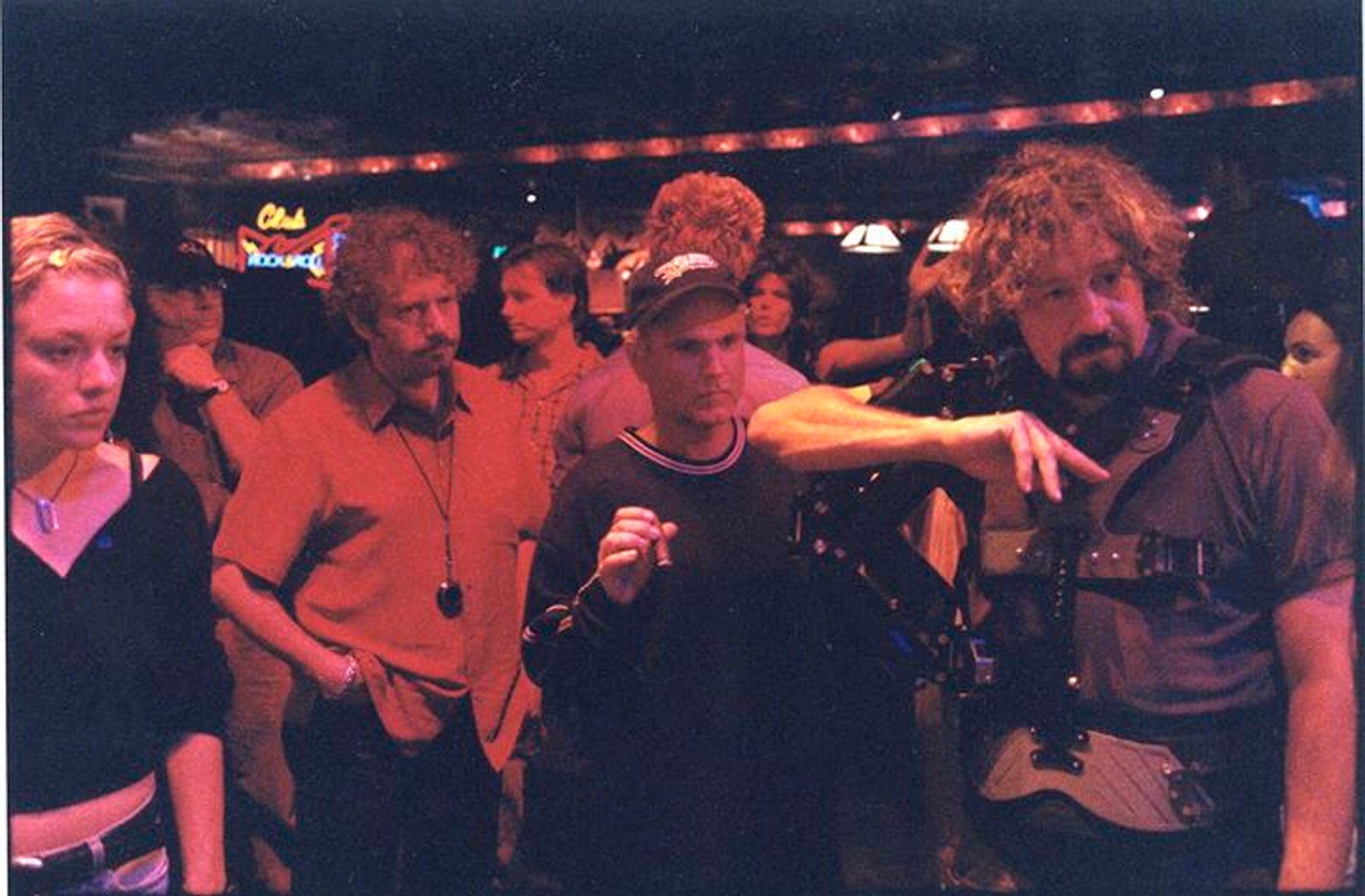

Dan Kneece planning a Steadicam shot on the set of "Rock Star"

As the DP, you also think, but your main job is guiding the crew. The Director of Photography is a unique job in that it is creative, physical, practical and psychological. You must learn the personalities of every person on the set and how that affects your job and the project at hand. How you approach someone may or may not get the expected reaction so plan accordingly. If you were a shrink, this would be the time you’d have your subject lie on a couch and ask them about their father. On set you don’t have that luxury, you have to formulate an approach, on the fly, as you walk from breakfast to set.

Before anyone will talk with you or get a light for you or allow you to photograph them or offer advice, they must trust you implicitly. I did a film with English focus puller Cedric James who told me, “I never make suggestions as when you do and they go wrong, you’re the one that made the bad suggestion.” These are words that I have taken to heart and remind one of, “A good child is seen and not heard.” Always be sure that when you offer up a golden nugget it is indeed well polished and presentable. Don’t constantly offer suggestion after suggestion after suggestion. The thinkers need to think.

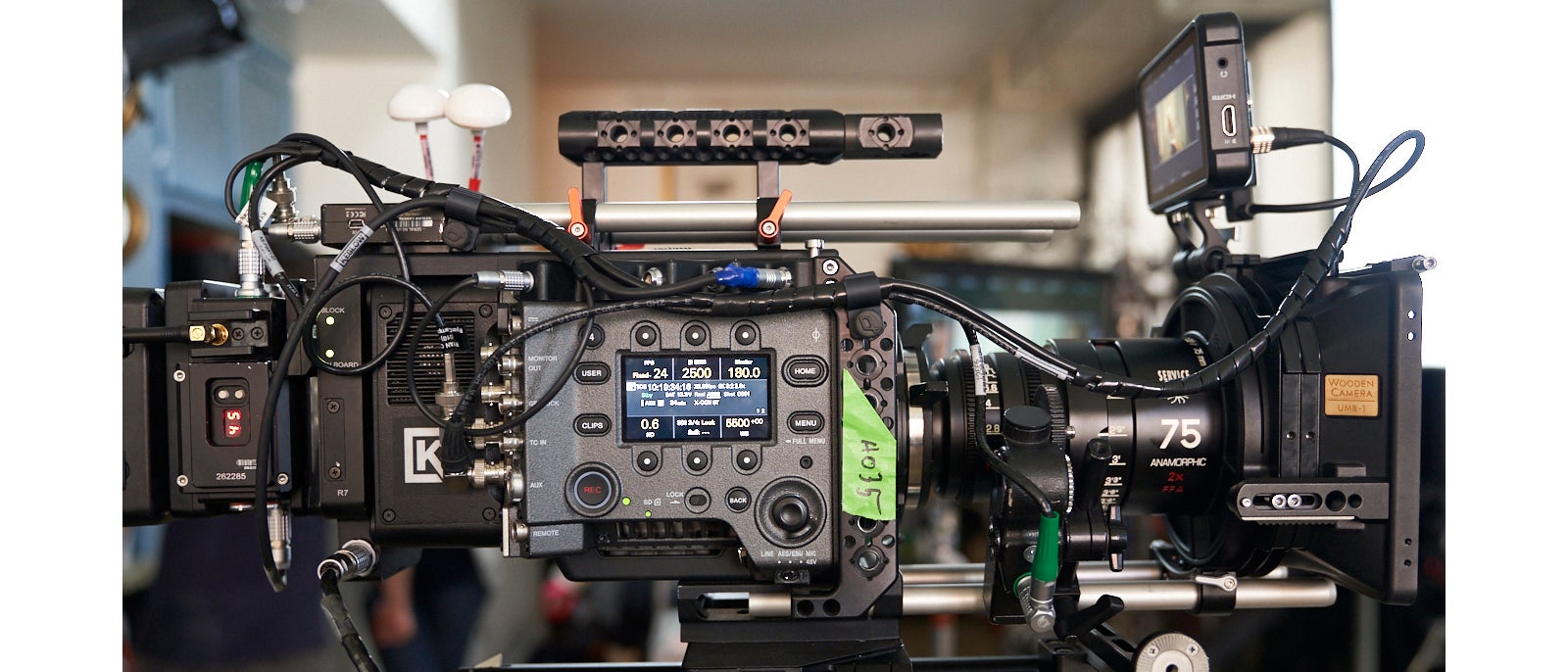

At this point, you’ve read the script several times, brainstormed with the director, met the actors, seen the locations, lined up your keys and gotten all your ducks in a row. This isn’t your first barbeque. There are certain constants you already know you will need. The basic camera, lens, support and lighting components are in your plan, but what else might you need, how might you use them and do you carry them for the whole show or bring them in and out on an as needed basis? Can they be delivered or do things need to be arranged logistically? Are you in town where things are available or do you need to move heaven and earth to get them. Is it worth it or can you get your work done another way? Do you need the Musco Light or can a tweenie do the job?

If your script were a zoo and each scene an animal how would you wrangle them? The opening scene might be an enraged tiger that hasn’t eaten for weeks. How and what do you feed him to survive without dying yourself? Is he a normal tiger or is he vegan? Can you be intimate with him or must you keep your distance? Silly concepts I know, but your scene may require special treatment.