11-12-2020 - Case Study

The Journey to Shooting Big Films – A Conversation between DP Brendan Galvin and Director Steven Bernstein

By:

Steven Bernstein: I’m here with Brendan Galvin, an esteemed cinematographer who recently shot the film "Unhinged" on the Sony VENICE. The film stars Academy Award winner Russell Crowe. Brendan and I worked together early in his career and we have been friends for more than 20 years. Let’s begin with the origins of your career.

Brendan Galvin: I finished school in Ireland and had no idea what I wanted to do. I did not come from a family that was involved in the film world, in fact, the only films I probably saw as a child were a couple of Bruce Lee movies, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang and Charles Bronson movies, anything with a bit of fighting. By chance, I started working at the Irish television station in the mail room. I liked what I saw and found out there was a Communication in Film course in Dublin, so I went to college and I loved it.

When I left, I knew I wanted to make movies but didn’t know how to go about it, so I joined the film union as a trainee, then started to get work. Every time I worked on a film I would ask if I could have the short ends. (Short ends are the ends of film rolls that are too short to be used for a whole take so they were normally discarded). Then I would shoot a short film or a music video for no money using those short ends. That was when I met you, I was a first AC. You had come to Ireland to shoot a feature film called Moondance. I was recommended to you and we worked together. It was a great experience for me. I learned a lot from you.

Later I got an opportunity to work abroad in Namibia as an assistant on a commercial with the director Tarsem. Paul Laufer was the DP. After that we did a couple more commercials together. Then Tarsem had a Coca-Cola commercial shooting in India and Pakistan that Paul didn’t want to do. Tarsem asked me if I wanted the job. That changed my life. After that I started getting lots of offers for work, not because anybody saw my work, but because I had worked with Tarsem. I was happy for all the work but it kind of tells you a little bit about our business. It’s not always what do you, sometimes, it's who you do it with.

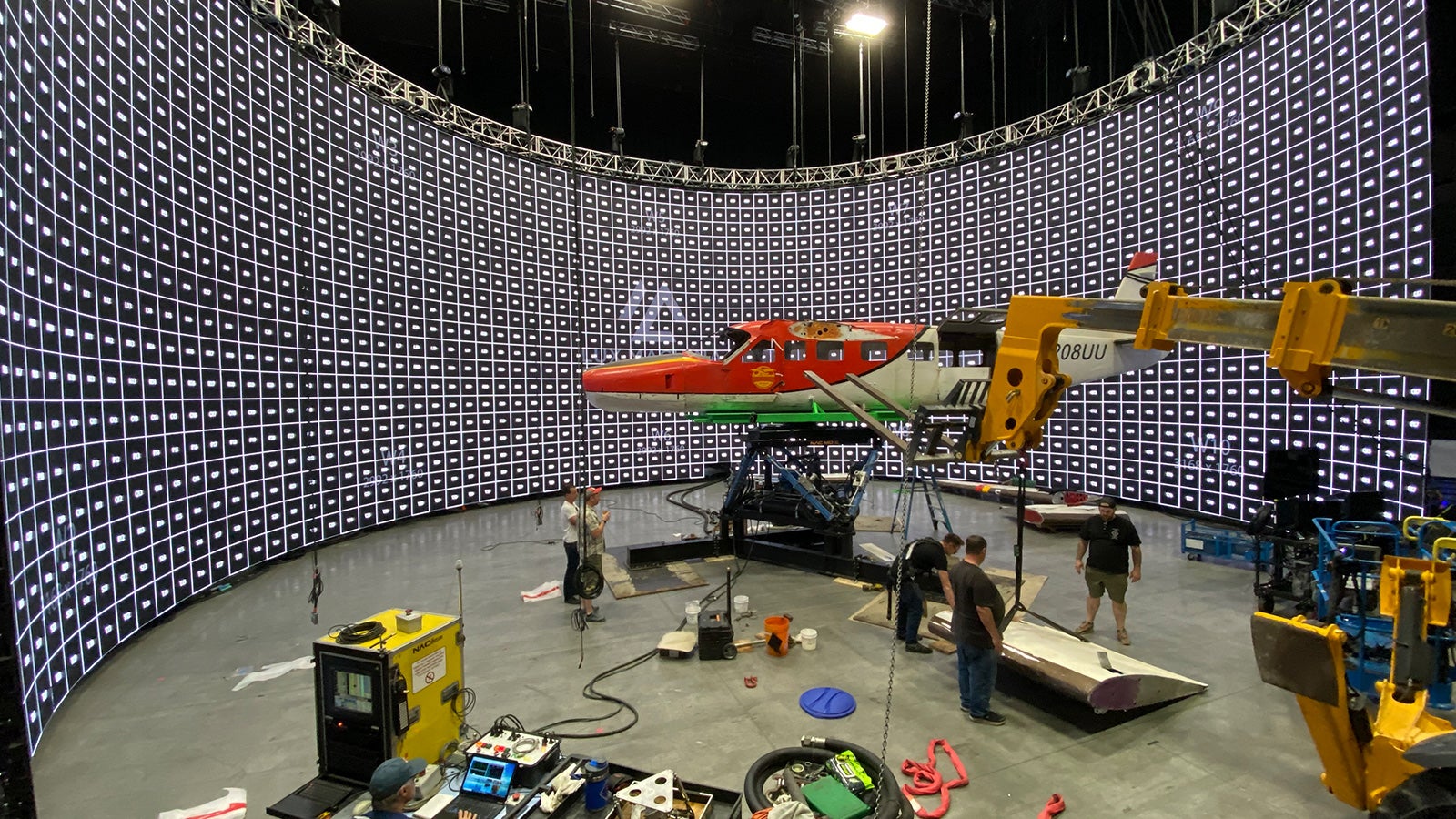

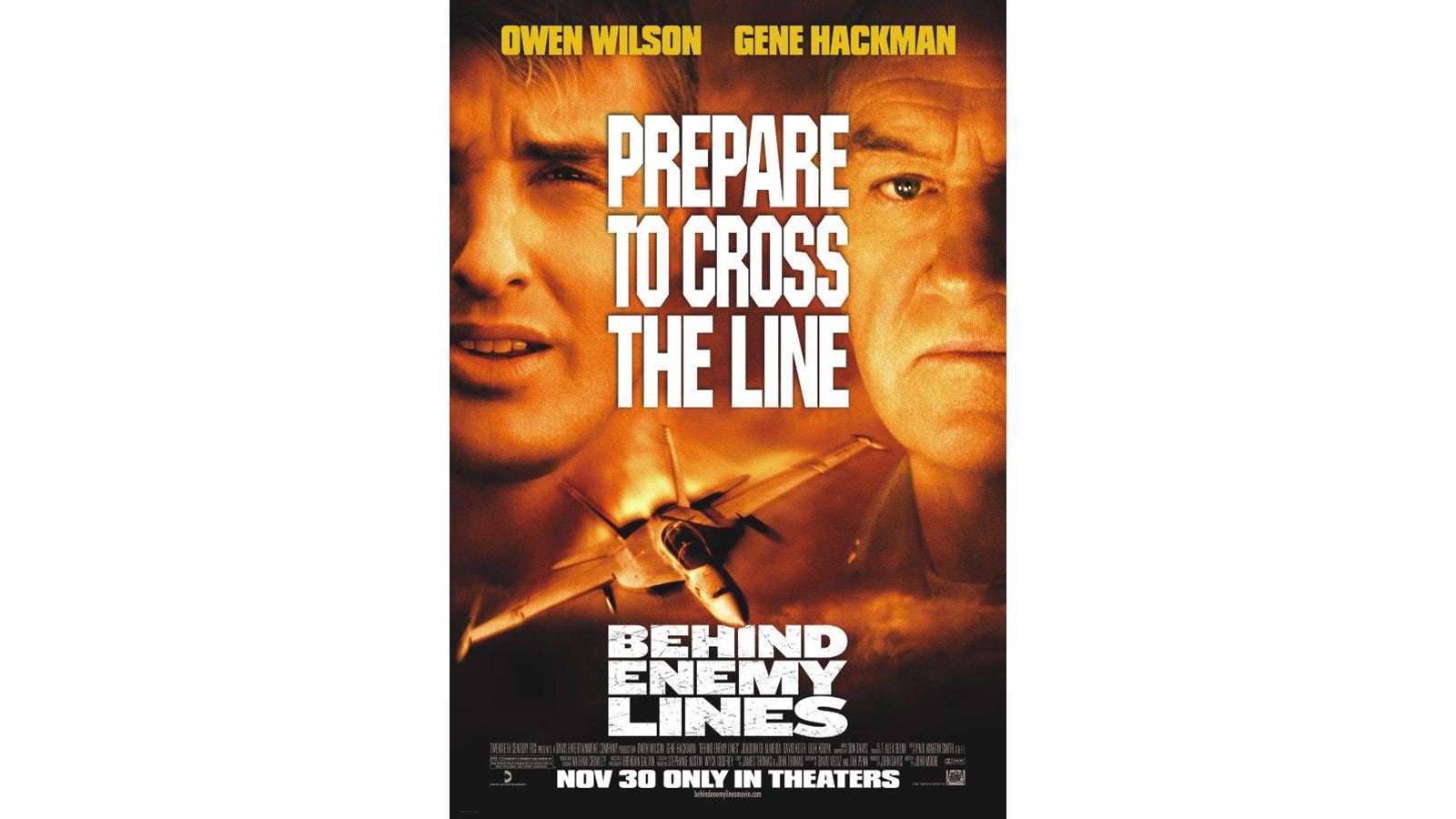

So that was it. I was now shooting, mostly commercials. I had done a few very small films for no money in Ireland, but the first film of any size that I did was a film called Rat. Steve Baron was the director. That was a really good film; we shot it in Dublin. I then went on to do Behind Enemy Lines with John Moore. John and I had known each other for many years. Nathan Crowley was the designer. It was early in his career too. Now of course he does all of Christopher Nolan’s work. Behind Enemy Lines was a studio film, which was something new and different for me. We shot most of it in Slovakia and a little bit in the U.S.

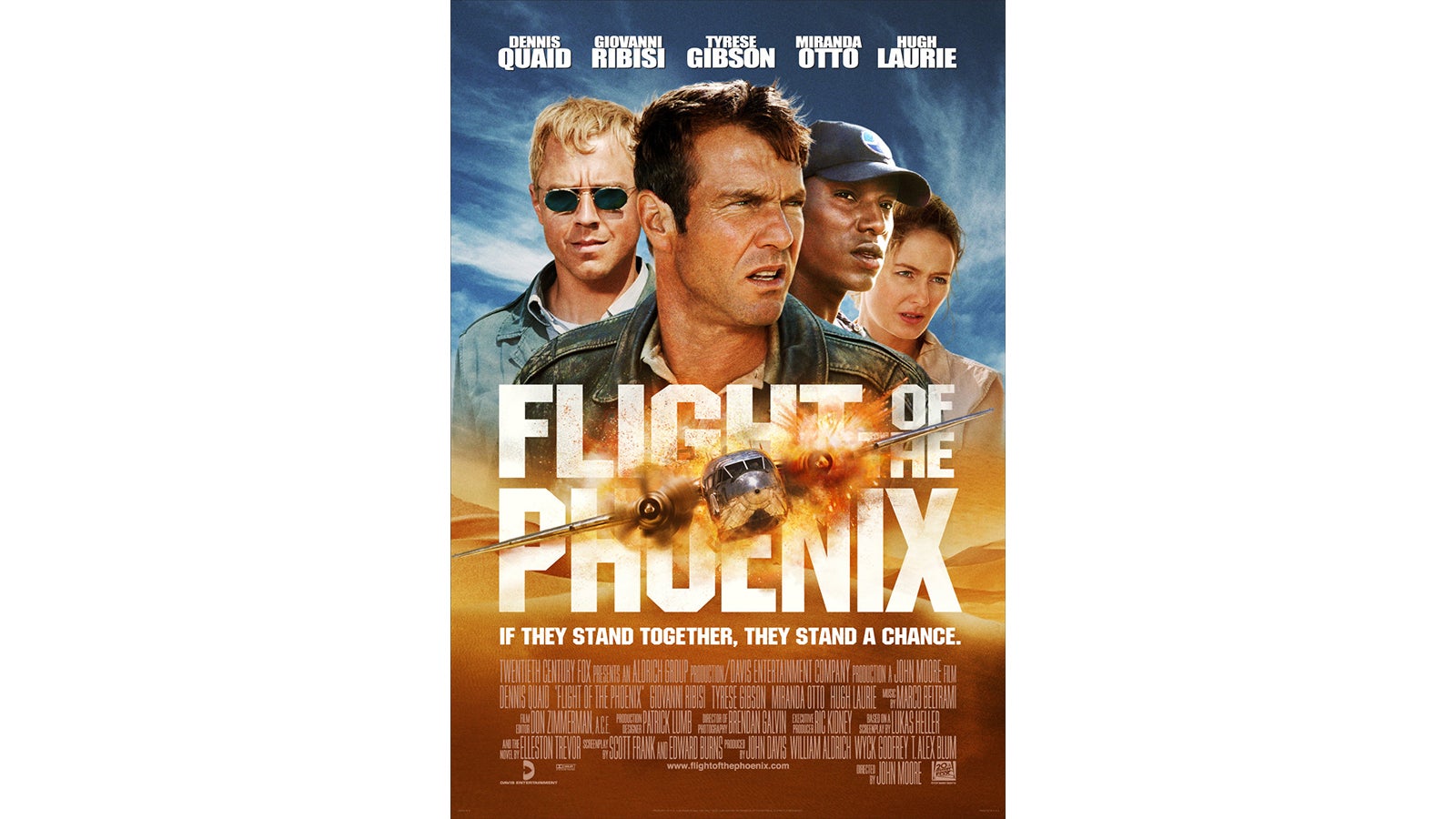

Steven: You did Flight of the Phoenix with John as well, didn’t you?

Brendan: I did Flight of the Phoenix after Behind Enemy Lines. In between those, I did Thunderbirds with Jonathan Frakes directing.

Steven: Big films. What is interesting for me, because I came up via a different route, is how a camera assistant moves up to operator and then to DP. How did you acquire those skill sets? I’m sure the course you did supplied a certain amount of information, and I think film school is great for theoretical understanding, but the real practical understanding of lighting can seem an insuperable obstacle to someone who hasn’t done it before. How does someone acquire that understanding? Through being on film sets and observing others? Or is it study? Is it discussions with DP’s? Or is it just sort of making it up as you go along and learning on the fly?

Brendan: I don’t think there’s one answer for everyone. You can talk to people, you can get advice, but I think you have to find your own route. The course I did, I really liked. We shot Super 8 and some video, we did radio, we studied film theory. We studied sociology, psychology, philosophy, and French. Computer studies. Drama. And it was a very ‘make it up as you go along’ kind of course. As for lighting and framing, most of what I learned came from taking photographs. I learned the most from processing my own film, messing with the processing.

Steven: With these stills, you were shooting film, obviously pre-digital, so you were processing your own film, and I’m a huge advocate for this by the way; doing everything. Because for me, in my own career, I’ve been a director, writer and cinematographer, and I realize that each thing informs the other. And I’m a better director because I was a cinematographer. But I was also a better cinematographer because I did still photography and a better director because of my background in theater. My writing is better because I understand the visual language of film. All these things tie into each other.

Brendan with Tarsem, Julia Roberts and Lily Collins on 'Mirror Mirror’

Brendan: Early on I used to think one of the reasons why all of my stuff didn’t look as good as DPs like Gordon Willis and Philippe Rousselot was because they had all this equipment that I didn’t have. Within a couple years of starting as an assistant, I was fortunate enough to get to work on a film with Neil Jordan directing and Philippe Rousselot shooting. We did this big night exterior in Dublin, all around a square. All Philippe used was paper lanterns with some photoflood bulbs. And I remember thinking that night that this was stuff in every student’s apartment. That was the irony of it, he got amazing images from just household bulbs.

Steven: I think, very often people intimidate themselves because they believe the world they’re not part of is more mysterious and more complicated than it is. But it’s not as complicated as people imagine. Even big lighting set-ups are simpler when you actually break them down.

Brendan: I think that’s what you have to do. In the beginning, I know that can be daunting, you can get freaked out by that. But sometimes it’s just using the light that is already available to you. When you have to light a football stadium at nighttime, you can sometimes do an easy thing and just turn on the stadium lights. And sometimes that can look pretty good.

Steven: I think of Chris Doyle when you say that. He changed the way all of us approached lighting because he would mix lighting sources with no concern about color temperature.

Brendan: Yes. A big film for me at the time, talking about mixed sources, was Paris Texas. Robby Müller was the DP. That was a huge film for me because he mixed a lot of colors. And they used practical lights.

Steven: Yeah, it is a spectacular looking film and it's interesting how DP’s are influenced by other DP’s. When I think of my own career, certainly, I drew on painting and photography most of all. But I remember early on seeing the film Days of Heaven, which overwhelmed me visually, so naturally it influenced me; the magic hour photography, the use of every inch of the widescreen, the boldness in the photographic choices. Still one of the best shots in cinema is the silhouette of the steam train going over the bridge.

But for you, as I look at your career, you worked with some of the greatest living DP’s and some incredible directors. Tarsem was working at the Spots commercials company the same time I was. We knew even then he was revolutionizing TV commercials. His work was absolutely stunning. He's a remarkable visualist. How would you say working with him influenced you as a cinematographer?

Brendan: I learned an enormous amount from Tarsem. But they weren't things that were obvious. Some of his images some people think are incredible because they're so perfect and everything is very balanced, he can do that without much effort. That's just an ability he has. Tarsem shoots incredibly fast. I mean, people think that to get these images you shoot slowly, but sometimes he liked to shoot documentary style; but at the same time with precision. Precision in his framing, and how it all cuts together. But technically? I shot many jobs with him with one camera in a backpack and two lenses. That was it.

Brendan on set

Steven: I think what you said about still photography is very interesting. You frame things in the world, and in so doing you see the world in a new way. For me it’s the same for writing. I don't think clearly until I write; I organize my world through writing and I think more clearly after I've written than before. I just find it strange when people try to outline a screenplay, I mean, how do you know where you're going until you've been there? So, I like to do it backwards and write first and then figure out what I meant to say having read what I've written. I think it’s the same thing with cinematography.

Brendan: Yeah. I've worked with several directors that began their careers as still photographers. With them, I don't like using words to communicate visual ideas. I just think it adds to confusion. My version of dark and yours could be quite different. It's much easier to show what you think. I used to use Polaroids to work out the visuals with the director.

Steven: You mentioned documentary, and how fast you sometimes work. Do you feel that contributes in some way to getting a better or different image?

Brendan: I think it helps but it depends again what you define as speed. I know that I work better when it's a little bit more instinctive. If I have too much time to think about something I don't think it's as good. When working at speed it’s more instinctive and more fun.

Steven: One of the reasons I like to use multiple cameras is that you get through the shooting day more quickly and the actors feel more engaged. I also remember doing music videos early in my career and in the mornings we would go much more slowly and then in the afternoons when everyone was panicking the camera would go on the shoulder and we'd be working quickly. Looking at it later, my work would be better in the afternoon than it was in the morning. So, it's not always appropriate, but I think it's a really interesting concept.

Brendan: It absolutely is. But again, it's knowing the right speed. Too fast is chaos. It's working at a speed where people are engaged, but can still concentrate, yet be instinctive, at least in part.

Steven: It's a great point. Thinking too much sometimes subverts art.

Brendan: Same with equipment. Having too much equipment can distract you, slow you down. The film becomes about the gear and not the quality. If somebody says to you you've got to shoot a film with one camera and one lens and one light, it’s funny but your decisions become more about the art and what is important. There is a great focus and clarity. Look, you can’t shoot big action films that way, but there is an important principle there to think about.

Steven: And big crews also can be an obstacle. When you have a lot of lights, a lot of cables and a lot of crew, suddenly you're carrying this caravan of people and the conversation and the noise increases on the set and everything slows down. This doesn't mean that you can shoot big films with one camera and two lights and a crew of five, but you also have to recognize when you have these big crews they're not always efficient, though they are often necessary.

When you're doing a really big film, you really do need big crews and everyone has a function. But again, there is a sweet spot. Behind Enemy Lines was a big movie and you had only done relatively small films and commercials. Suddenly you're a DP on an enormous action film. Your first day on the set of a big film as a DP. Were you scared? What were you scared about? How did you overcome it? What happened?

Brendan: Well, your first day on a set isn't your first day on a film. You have been figuring things out during prep. Fear is a bad thing. So is panic. The same way fear can spread, panic can spread. Happiness can spread too, and encouragement can spread. So, I had decided that whatever I was feeling, I wasn’t going to show fear or panic and I was going to encourage the crew.

Your first shooting day is a big day; it’s the first time you put everything together. You want to get everyone to feel comfortable working with each other, so we decided to shoot something that required a lot of the crew, but was low pressure before the first day of major photography. I think it's useful to do something low pressure like make-up tests or wardrobe tests. On Behind Enemy Lines, we did a make-up test with Owen Wilson which is a bit funny. We weren’t sure why we were doing a make-up test on a male lead in an action film, but the chances are it was a test of me and John. Now understand, this was our first Hollywood movie.

We had decided we were never going to use a light on any exterior on the film. That was our plan. We arrived at Griffith Park to do this test and there was a 40-foot grip truck and a 40-foot electric truck and we hadn't asked for them. I looked at John and said “John we're not going to use any of this”. And we shot the thing and several times we were asked by the producer “Are you sure you don't want anything?” And the gaffer kept coming up and asking “Are you sure you don't need anything else?” And then one of the studio executives made a phone call and I didn't know what the conversation was about, but I don’t think he was happy.

The next day we went in to look at the tests on the Fox lot. After the first couple of frames the same studio executive got on the phone and said you've got to come down here and look at this stuff. They liked it. And that’s pretty much how we shot the film.

Steven: That's incredible. How did you get exposure?

Brendan: Well, if it was too dark we didn't. We stopped shooting. That's what it came down to.

Steven: Well, what if it was afternoon and the sun was directly overhead for example? Were you worried about shadows under the eyes or the audience not being able to see key details? Would you bounce light into the eyes or just let the eyes drop off, or would you have diffusion overhead?

Brendan: I can't remember exactly but I'm completely in favor of putting a butterfly overhead. I did a film with Sly Stallone called Escape Plan. We went to do a shot of him in an old-style phone booth. You could see through glass on three sides. He arrived on set and the first thing he asked me was “Where's the butterfly?” And I said we don't need it. He obviously wasn't used to this. But it worked. Sure, sometimes you want to see the eyes. But sometimes, the audience doesn’t need that. Sometimes it’s better if it is more natural.

Steven: Go back for a second. Weren’t you scared that the executive who made that phone call was going to get you fired? Those things happen. DP’s sometimes get fired. Were you at all frightened?

Brendan: No, I was blissfully ignorant. You can only be afraid if you know what to be afraid of. Why would they fire me? As far as we were concerned, this is how we were going to shoot the movie. We knew it could work. Shooting in Ireland we were used to bad weather, changing weather and making what we had work. And it would look good. People get used to doing complicated rigs. They should ask, does it really look better? And what is better? What is pretty? What is natural?

Steven: I understand, but lights and big overheads give you consistency. When I shot in Ireland I had lots of overhead diffusion and lots of lights. So that even as the weather changed the image could remain the same. I remember shooting on the beach with you in West Cork. Sun, cloud, rain, wind, sun and then dark. Even with all the rigging, the background kept changing. It was very hard. I understand the advantages of both approaches. The approach a DP decides to use can vary significantly but I think it needs to be appropriate to what you are shooting. For example, when you’re shooting a big TV series like West World, which you shot, matching exterior light is usually more of a requirement.

Brendan with Derrick Borte, Director of "Unhinged"

Brendan: I know DP’s who refuse to come and shoot something in Ireland because they just think life is too short. You end up not actually creating a look but just struggling just to get it to match. But some of that comes down to how long the shot is going to be on screen. If it’s action and the shot is only on screen for a few seconds, no one is going to notice. I'm not suggesting that people shouldn't learn technique or rules for that matter. But most creative people I know break rules all of the time, but they understand what they're doing when they're breaking them. I used to be far more concerned about continuity than I am now and when I say continuity, I don't just mean the length of a cigarette. I'm talking about everything. I feel you can get away with anything as long as it doesn't take the viewer out of the story. I think that's a skill, knowing what you can get away with.

Steven: You can get away with a lot. Young DP’s and young directors don't always realize it, that audiences get so engaged in the story, hopefully, that they lose track of how long a cigarette is or whether someone's button was undone. People sometimes surrender the good in the pursuit of the perfect and sometimes the perfect isn't perfect at all because you've lost sight of the thing that's most important; the substantive drama on the screen, not the small background details. So, I cheat all the time. I cheat the direction of the sun, I cheat the eyeline to get a better close-up of an actor. I bend everything to serve the drama. It’s not about breaking rules, I think for the most part there are no rules. It’s art. If it works for an audience emotionally, it’s valid.

You know, another interesting thing that a DP does is lead a crew. You rightly say a DP can inspire a crew. But a DP can also subvert the whole enterprise. So how do you lead a crew? And what was it like going from camera assistant to camera operator, to leading a big crew as a DP?

Brendan: It’s hard, of course, but it’s also not that hard in some ways. A film set is a highly pressurized environment even when things are going well because if something goes wrong there is a lot of money at stake. You have to give people respect. It doesn't matter whether they're a director or somebody getting you a cup of tea. Everybody deserves respect. If you give it, you generally get it and the unit runs better. Also, as a manager of people, and a DP is a manager of people, delegation is important. I wasn’t great at that at the beginning. But I learned a valuable lesson on Flight of the Phoenix with the gaffer Michael McDermott.

I used to fiddle with a particular light every day and then one day I didn't do it. After we had done the shot, I realized that light hadn’t been turned on. Michael said to me “Brendan you have done that light every day for the last week. We presumed, like always, you would continue to do it.” He was right and from that moment on I understood how important it was to pass along information; to make sure your team is engaged.

I allow the gaffer to run the electrical department. I allow the key grip, to run the grip department. I know a lot of DP’s who are very talented, but they fall down when it comes to managing the crew. And I think if you can't manage the crew you don’t get to do the creative stuff in a way that you’ll enjoy. I think a huge responsibility all of us have to ourselves is to enjoy the day's work. I can't do that if I'm shouting and screaming at people. Also, if your crew isn’t enjoying their work, they just aren’t as good. And some part of them won’t be looking out for you, or the film. They will just be trying to get through the day without getting abused.

Steven: I think you make a great point. I think that a crew has to feel part of the process. At the beginning of my career as a DP I made the same mistake as you. I would be doing everything, and I stepped on a lot of toes to try to prove my value. Maybe it was more efficient for me to move a light, rather than explaining to someone how I wanted the light moved, but it wasn't more efficient for me to alienate the crew. So, although you may lose 5 percent in efficiency by having to tell someone else to do something, by facilitating and inspiring a crew, you end up with a better film. That crew also has a wealth of experience and when they feel you are open to their contribution, they willingly contribute.

About the author:

Steven Bernstein, DGA, ASC, WGA is an ASC outstanding achievement nominee for the TV series Magic City. He shot the Oscar winning film “Monster,” “Kicking and Screaming,” directed by Noah Baumbach, “White Chicks” and some 50 other features and television shows. The second film he wrote and directed, “Last Call,” stars John Malkovich, Rhys Ifans, Rodrigo Santoro, Zosia Mamet, Tony Hale, Romola Garai and Phil Ettinger, is scheduled for release November 25 in selected cities.

Steven can be followed at Stevenbernsteindirectorwriter on instagram where he regularly posts short insights and illustrations about filmmaking.