10-08-2021 - Case Study, Gear, Technology

Anatomy of a Scene: Loki - Shot on VENICE

By:

We take a detailed look at the show’s three-minute continuous sequence in the episode “Lamentis.”

Images courtesy of Disney Plus/Marvel Studios.

Published with permission of The ASC.

Thor’s mischievous brother, Loki (Tom Hiddleston), has found himself in quite a predicament. He’s been arrested by the Time Variance Authority for veering off his fated path and starting a new timeline “branch” that would have spurred the beginning of a multiverse. It’s a crime he’d never heard of and had no intention of committing. Now he’s on the run.

Episode 3 of Loki — Disney Plus’ latest series within the Marvel Cinematic Universe — sees our titular antihero teamed up with Sylvie (Sophia Di Martino), a female “variant” of Loki from yet another timeline, as they attempt to escape an inhabited moon that’s on the verge of destruction. They race through the chaos of a neon-splashed city to reach the last space-bound transport.

The screenplay for the episode — titled “Lamentis” and written by Bisha K. Ali — described this run for their lives as a long-take action sequence. In this month’s Shot Craft, we’ll take a detailed look at this three-minute continuous sequence, which was photographed by cinematographer Autumn Durald Arkapaw.

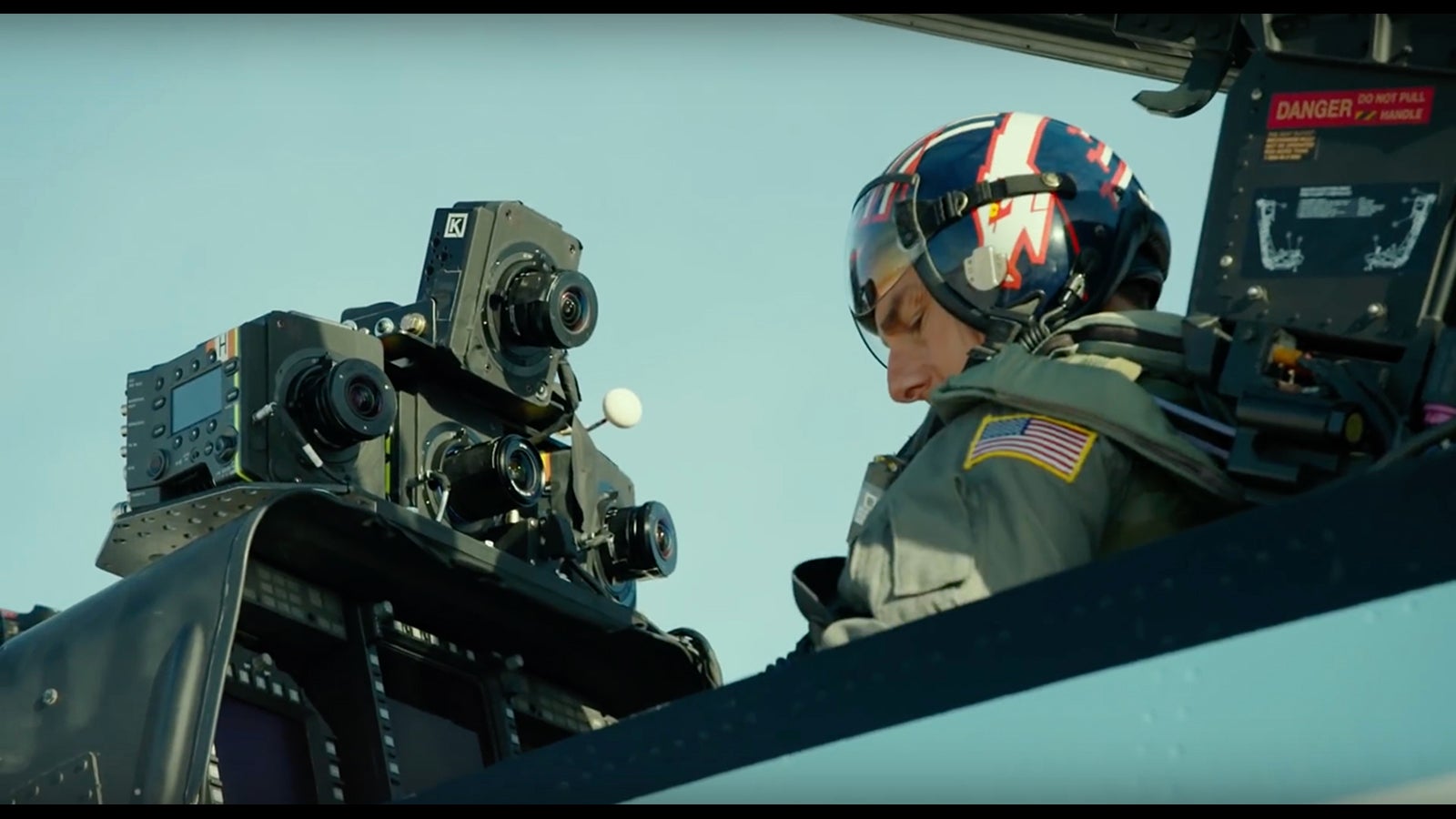

Cinematographer Autumn Durald Arkapaw plans a shot.

Determining Direction

The first season of Loki was directed by Kate Herron, a relative newcomer whose previous work includes the series Sex Education and Daybreak. Alongside her for the entire season was Durald Arkapaw, whose credits include The Sun Is Also a Star (AC June ’19) and the upcoming Black Panther: Wakanda Forever. The duo began discussing how to capture this sequence in “Lamentis” when they commenced prep for the entire season, and Herron embraced the “oner” concept very early on.

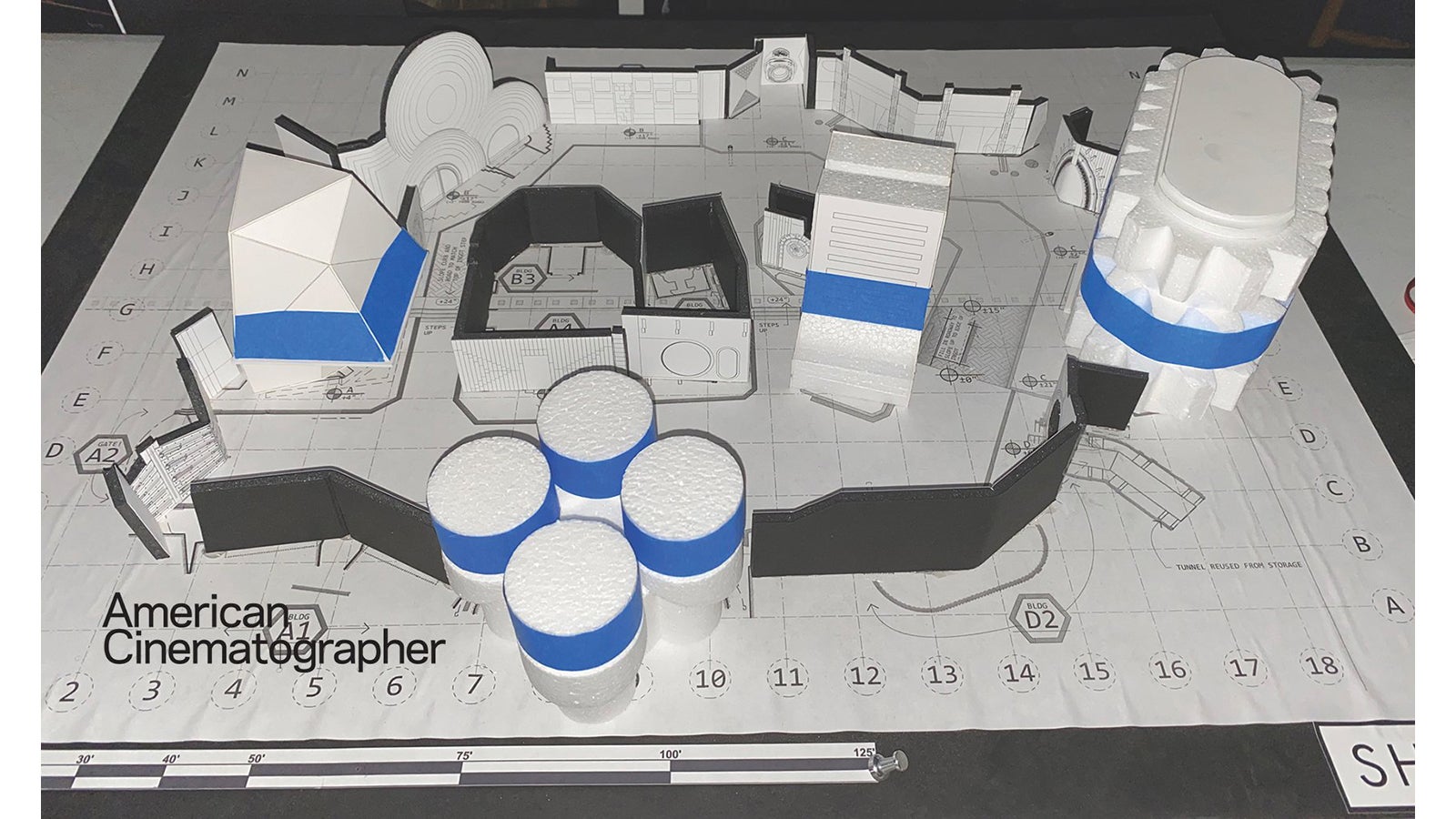

Prep began in October 2019 but was soon halted by the Covid-19 pandemic. Herron, Durald Arkapaw and production designer Kasra Farahani stayed active during lockdown, however. The planning for this oner sequence officially took about one year — from the start of prep until the shoot in November 2020. The extensive rigging and pre-lighting took four weeks. Farahani kicked off the process by designing a 350'x200' circular city set that would ultimately be built on the backlot at Pinewood Atlanta Studios (now Trilith Studios), and by creating a cardboard-and-Styrofoam miniature the filmmakers could use to previsualize the sequence:

A cardboard-and-Styrofoam miniature of the set for previsualization, built by production designer Kasra Farahani.

The early concept for the sequence involved a motorcycle chase through the streets, but that idea was abandoned in favor of a more intimate foot chase interspersed with several moments of hand-to-hand combat.

“Kate stepped back at one point and asked, ‘What does this sequence mean? What role does it have to play in the story?’ And we realized we might be throwing too much at it,” recalls Durald Arkapaw. “We decided to make it more humanistic, and that’s when we dropped the motorcycles and went with a foot chase.”

Planning and Preparations

Several iterations of 3D previsualizations were created for the sequence by The Third Floor. The discussions started with the general blocking: Where would the characters enter, which path would they take, what obstacles would they face, and how could the shot be broken down into smaller pieces to be shot over several nights?

“Certain aspects became givens,” Durald Arkapaw says. “In the story, the dying moon is about to be destroyed by a crumbling planet above it, so we’ve got to look up several times to see what’s coming. Since we’re shooting in 2.39:1, that meant a tilt up, so there are moments when we knew we were going to look at the planet, and those could be natural stitch points because we’d be looking at a completely CG creation.

“Then Richard Graves, the assistant director, timed out the sequence, so we knew when the practical-special-effects or visual-effects moments would happen, and when the actors would be running into a certain area and out of that area into the next,” the cinematographer continues. “Ultimately, we decided there would be seven stitch points in the shot, where we could break it down into individual nights to shoot each portion of the sequence.”

From there, the team did a physical walkthrough of the sets in progress to get a better sense of blocking, timing, camera positions and story.

To help break up the sequence visually, Farahani designed each section of the street to have a different base color, incorporating a large amount of fluorescent paint, UV fixtures and retro-reflectant lighting. “Kasra is a great collaborator,” says Durald Arkapaw. “He understands what a cinematographer needs, and he’s always thinking about that; he’s not just designing in a vacuum.

“We tested a number of fluorescent paints under UV light and picked the best, and then Kasra incorporated UV lighting fixtures into the production design so that the face of each façade had its own source,” she continues. “UV fixtures aren’t like normal lighting fixtures — it takes several of them to really work well, so a lot of them were built in. Then the art department designed all the LED signs and practical lights for the sets, and my fixtures foreman, Joel Warren, and data team built them RGBDT so that we could control any color or intensity on the lighting-console desk. The hundreds of [signs] were [all custom-made fixtures] — they did an amazing job. I didn’t do any movie lighting from the ground; everything was built into the set. I kept my lighting to overhead soft boxes and edge lights.” Josh Thatcher was the lighting-control programmer for the show.

Overhead was one construction crane and three Pettibone cranes with large box-truss softboxes. One held a 40'x40' grid with 64 Arri SkyPanel S60-C fixtures, and the other three were 30'x20' boxes loaded with 60 S60-Cs. These were augmented by six additional cranes with Nine-light Maxi Brutes for interactive lighting as the characters would make their way through the gauntlet.

“I like cyan moonlight, so we colored the SkyPanels a mint-like color for the glow coming from the planet above — and then feeling the warm edge from the explosions on the actors with ½ CTS on the Maxis,” Durald Arkapaw notes. “We had everything connected back to the lighting-console desk, so gaffer Brian Bartolini and I would look at the rehearsals and adjust intensities of architectural lighting, as well as our overhead planet ambient and edges, to shape the light as we went along.

“The integrated lighting effects supplemented both SFX and VFX; for example, when an explosion happens, we would shape our light on the talent accordingly. We had all of that timed out so that we knew at 37 seconds, a woman would throw a Molotov cocktail, and at 41 seconds, it would explode and we’d add in lighting to supplement. Then, at 1 minute 7 seconds, we’d add in lighting to simulate a large impact in the distance — and so forth.”

Once the choreography was roughed out, Durald Arkapaw broke down the sequence technically and determined that all of it would be shot on Steadicam by A-camera operator Andrew Fletcher.

Making It Happen

The sequence was shot over five nights. Durald Arkapaw shot the entire season with Sony’s CineAlta VENICE (at a base of 2,500 ISO) and custom-tuned T Series anamorphics that were expanded for full-frame coverage. The oner was photographed with a 40mm T Series lens.

“The exact methods we used for each section of the sequence evolved,” says the cinematographer. “We really decided things as we started to rehearse with the actors and realized that Tom is a very fast runner. We knew it would be too challenging for Andrew to keep up with Tom on foot, so we brought in a Grip Trix [electric camera car]. We knew we wouldn’t use it the whole time — there would be moments of stepping on or off it. We also knew we’d have to build a platform for the Grip Trix to ride on because the ground was uneven dirt, so we started to plan that out.

To read the rest, click over to https://ascmag.com/blog/shot-craft/anatomy-of-a-scene-loki

Overhead soft boxes provided the key light, while LED signs and UV fixtures created the set lighting.