11-08-2024 - Filmmaker Interviews

James Whitaker, ASC Harnesses the Experience of a Storied Career to Craft Cammy and Mike, a One-of-a-Kind Short Film

By: Yaroslav Altunin

When audiences and creatives talk about DPs, we define them by their style, creative and technological abilities, and body of work. But there are those who defy labels, able to invite themselves into any production and light the creative spark that elevates the project beyond expectations.

James Whitaker, ASC is one such cinematographer whose career is marked by collaborations with iconic producers and directors such as Gore Verbinski, Francis Lawrence and David O. Russell. From action-adventures to satirical dark comedies to thrillers and Marvel TV series’, and commercial work that showcases everything from tech, beauty and automobiles, Whitaker’s skillset and experiences has made him a master craftsman.

This is why it’s so fascinating seeing him tackle the humble short film.

Cammy and Mike, a short film created by Rob McElhenney (It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, Welcome to Wrexham) and directed by William Groebe, is both an experiment and a creative challenge. As a creation of ADIM, McElhenney's technical platform for creators and their creative projects, Cammy and Mike leans heavily on the aspects of filmmaking that even the most experienced professionals have anxiety about—working with VFX and wild animals.

Sony Cine sat down with Whitaker to explore the creative journey of Cammy and Mike, uncover his unique workflow to overcoming those anxiety-inducing obstacles, and discuss how the Sony VENICE 2 may have been the only choice to bring this short to life.

Watch Cammy and Mike film by clicking above

James Whitaker ASC: Lessons From Mentors

"I got in the business quite young," Whitaker said. "I grew up in the North Shore of Chicago, where they were making all the John Hughes movies, and so I would ride my bike down with all my buddies and check out what they were shooting, whatever might be—Ferris Bueller's Day Off, Uncle Buck, 16 Candles."

Whitaker earned his stripes working on Roger Corman movies, who was known for working with new creatives and helping them move up the ladder. This includes a long list of creatives with storied careers—Januzs Kaminski, Martin Scorsese, James Cameron, Francis Ford Coppola, and even Ron Howard.

"I started all the way back with Concorde Studios (Roger Corman’s company)," Whitaker shared. "You move up very quickly there. On your first movie, you’re a film loader, next movie, you're a second (AC), next movie, you're moved to first (AC), even if you don't know what you're doing."

While making indie films taught great lessons and sparked creativity, Whitaker jumped into the commercial world to find financial stability. Oddly enough, this would lead him to work with Harris Savides on a commercial with Tina Turner and turn him back toward the indie world.

"I was cleaning some filters on the back of the camera truck, and (Savides) came up to me," Whitaker said. "He said to me, 'Hey, I've seen you around on a few of my jobs now. What do you want to do?'"

"And I said, 'Harris, I want to do what you do. What's the secret?'"

Savides told Whitaker to stop crewing, buy himself a Bolex camera, and convince all his friends to be directors.

"And that's pretty much what I did almost immediately," Whitaker explained. "It's been one step at a time getting to a different spot, and you have breakthroughs along the way."

Since his days with Savides and Corman, Whitaker has shot countless commercials, series, and films, including Thank You For Smoking, Running Scared, Amazon's Patriot, and Marvel's Hawkeye. Whitaker just wrapped photography on Gore Verbinski’s film, “Good Luck. Have Fun. Don’t Die!” and is about to start photography on Steve Conrad’s HBO Series, “DTF St. Louis.”

Throughout such a storied career, Whitaker has acquired an extensive skillset that allows him to flow between indie sets focused on character development and huge sound stages with heavy VFX elements. Bringing such a wealth of experience to Cammy and Mike may seem like overkill, but Whitaker was challenged extensively as the short film mixed VFX plates, working with animals, and shooting with pint-sized CGI characters.

To top it off, it was all shot at night.

While the cinematographer isn't always predisposed to using a certain camera tool, Whitaker knew early on that the Sony VENICE 2 was what he needed to capture Cammy and Mike.

Working with Robots, Bears, and the Sony VENICE 2

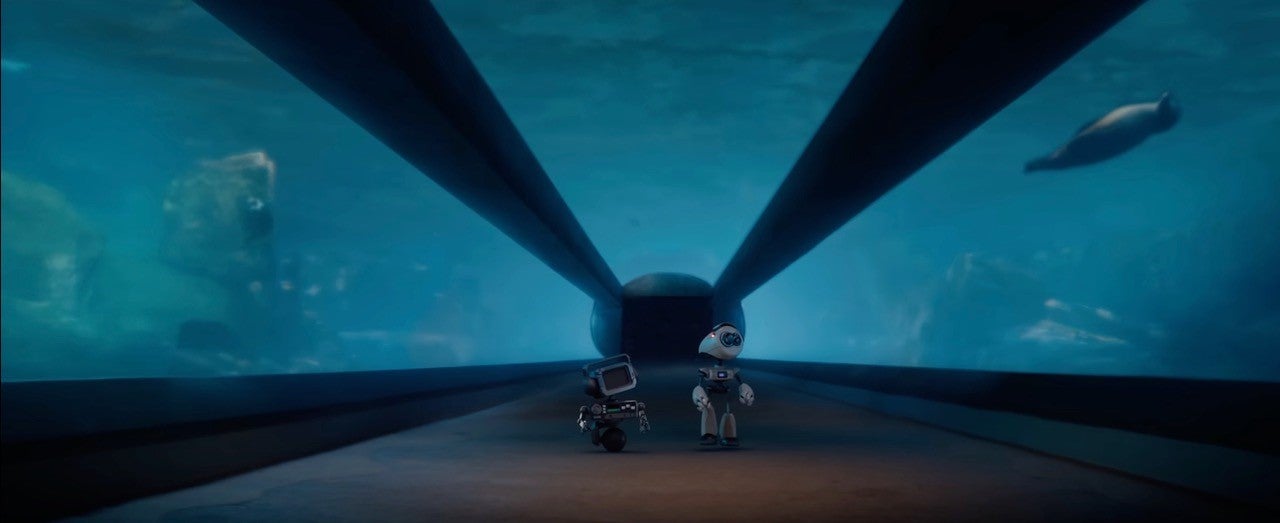

The short follows two alien robots that come to earth to catalog the animals of the Green Peak Animal Sanctuary. Cammy, a camera-based robot, and his audio-based cohort Mike, come into contact bears, snakes, and sloths before they inadvertently let out a baby wolf. After some struggle, they manage to return the cub and plan to head home, only to discover the big, wide world of Los Angeles.

Created as part of the technical platform ADIM—a space for creatives to start, manage, and monetize their projects—Cammy and Mike finds itself part commercial and part creative challenge.

"It was a cool opportunity because I've been working in advertising as well as making movies and TV shows for a while now," Whitaker explained. "Whenever you start breaking the mold of what advertising might be, and especially when it starts to blend between the advertising world and the filmmaking world, it gets really exciting."

Cammy and Mike showcases what ADIM can achieve as a platform but also forces the filmmakers to deal with the challenges of working with wild animals, VFX elements, and shooting at night.

"My first conversation with Rob McElhenney was about how he wanted it to be big. He wanted it to feel big. He wanted it to feel dark," Whitaker explained. "And he was like, "Listen, I want this to feel like a movie. I don't want it to feel like something that's polished and bright. I want it to feel dark and a little ominous.'"

"I thought it was just a magical little story."

With this concept in mind, Whitaker began his prep for the show. But as the plan for locations was coming together, issues quickly began to pop up. Since some animals were in the middle of their mating season, shooting opportunities were limited, and so were the lighting options Whitaker could use.

"Initially, the idea was that we were going to shoot at the LA Zoo, the LA Aquarium, and at the old zoo," Whitaker explained. "And they told us that we would not be able to bring any lighting to the aquarium."

"They told us that we may be able to bring one or two lights to the LA Zoo," Whitaker continued. "And even at the old zoo, where we'd be able to do more lighting, they wanted to know every lighting unit we were bringing, and even told me we couldn't bring certain lights because they were too bright because they didn't want to bother any of the natural wildlife at Griffith Park and at the zoo. I appreciated this. To be honest, sometimes it's great to be pushed into a direction and have to work within limits in order to stretch yourself creatively."

With little opportunity to extensively light the night exteriors, the decision to use the Sony VENICE 2 as the capture system was an easy choice.

"Right away, I went to the VENICE," Whitaker said. "(it was) just going to make sense to be able to use the dual ISO mode at 3200 and know that I'm still going to get a very clean image and have amazing image fidelity."

When shooting at the old zoo, the former location of the LA Zoo, Whitaker had to create all the lighting from scratch. Any practical lighting was removed when the location was abandoned, so when the sun sets, it just ends up being a black hole, as Whitaker called it.

"Everything had to be created. We had a couple of balloon lights, and a couple of strategically placed condors with LED lights. It sounds like a lot of lighting, but they're very small units," Whitaker explained. "And then we put some sodium vapor practicals alongside the cages and the enclosures where the animals were playing."

Using The Sony VENICE 2 to Overcome Unique Challenges

The story of Cammy and Mike posed greater challenges than just shooting at night. With VFX, extensive compositing, and wild animals in nearly every frame, preparation and execution needed to be perfectly balanced. Yet with Whitaker’s wide-ranging experience supporting the project, each scene was approached with creativity, allowing the team to embrace the cinematic movements of big-budget features, safely overcome any challenges, and quickly pivot when an obstacle presented itself.

"My job was going to be half shooting plates for animated characters, and then half the time would be shooting plates that included animals that were going to be difficult to work with," Whitaker shared. "And (Director Will Groebe) had storyboarded everything, and he had all these incredible cinematic tracking shots—the regular language of a big movie."

The journey of the small-statured characters of Cammy and Mike demanded sweeping camera movements. However, the plates had to be captured from their perspective due to their size, required several layers of technology.

"(Cammy and Mike are) moving around the rehabilitation center, and so you need to move the camera," Whitaker said. "Well, I think one of them was 12 inches tall and one was 16 inches tall…the lens had to be really low to the ground, and on something that could move with it."

"We ended up putting into play two cinema Scorpio cranes with matrix heads on them," Whitaker added. "On top of that technology, we put our VENICE cameras with our Xelmus Apollo lenses with a low-angle prism to be able to get the illusion that you're as low to the ground as possible."

"These cameras are literally scraping the ground as you're tracking back with our characters or pushing in, or whatever it might be."

Having this setup wasn't only beneficial for capturing low-to-the-ground POVs, but it also helped the camera crew stay safe when dealing with wild but trained animals, such as a bear, a rattlesnake, and a pack of wolves.

"It sounds like a really expensive approach…but the other part of the time, we were shooting with animals that are completely unpredictable, "Whitaker said. "Some of which we couldn't be close to. Like, we couldn't be close to the bear. Even the wolves, which were actually half-wolf, half-dog, we had to be some distance away from them."

To add complexity, these animals didn't always hit their marks, forcing Whitaker and his team to pivot mid-take.

"To be on these telescoping arms allowed us to maneuver quickly," Whitaker said. "The bear's not going to hit the mark exactly, so we could slide over three inches in the middle of a take and not have any operators in any sort of harm's way."

"It ended up being the perfect way to shoot everything. It made it so that we could move really quickly.”

For more complex shots—like the one involving a pack of wolves—Whitaker and his team utilized a pair of wolf dogs and repeatable camera movements to capture multiple layers of the same animal.

"There's a shot that incorporates like 6 or 7 wolves in the shot, where we only had two," Whitaker said. "And on top of that, there was a puppy wolf. But the puppy wolf was actually a dog, so you can't put these half-wolves with the dog. That'll be over very quickly."

"We had the repeatable techno dolly so that we would do wolf passes. Put a couple (of wolf dogs) in frame and then do our camera move…and we did that three or four times. Then we bring in the puppy with trainers in the shot and you've got a repeatable move already programmed with where the wolves would have been."

Having the VENICE on set wasn't all about low light. There were moments when Whitaker shot through ND in the high base ISO just to focus more on the tiny characters. But the internal ND was an asset on this short film for very different reasons.

"I knew we were going to be working at low light, but that doesn't necessarily mean that we weren't going to be able to be at a T/4 or deeper if needed," Whitaker said. "To have the internal ND capability of changing an N.6 to an N.3 really quickly, while you have a bear standing in front of the camera, proved to be very helpful."

Creative Tools For Breaking Creative Limits

Putting short films into a box can be an exercise in futility—a bit like trying to get a bear to hit his mark. It's an art form that seems to be forever free from the golden shackles of the box office.

This is evident in Cammy and Mike. While it can be classified as a commercial for ADIM, it is also a heartwarming story about discovery and adventure, crafted by talented creatives who make complex scenes look easy.

As Whitaker spoke more about his toolkit for Cammy and Mike, he spoke about his time with the VENICE on other projects. On a more recent film, where the story also demanded a big look, Whitaker experimented with what the VENICE could really see.

"There were times when I would turn off my lights and see what the VENICE is just seeing by itself," Whitaker said. "And I know now if I wanted a bolder approach and not have such a big look to the movie, that you could go much grittier and shoot at night and have something quite beautiful from that camera with just one light."

"I love that camera. It just blows me away every time," Whitaker added. "Sometimes, you look with your eye, and you're not sure you're seeing exactly what that camera's seeing. Sometimes, I think that camera sees more."

To see the Sony VENICE 2 test its limits, check out this article: Renan Ozturk pushes the Sony VENICE 2 to the extremes