02-10-2023 - Case Study, Gear

Shot on Sony: Behind the Scenes of ”Missing”

By: SonyCine Team

Missing is a story of a young girl’s (June) search for answers after her mother mysteriously goes missing while on vacation. As June unravels secrets about her mom, the film details June’s search through the perspective of the various devices she’s using – from cell phones, security cameras and computer cameras.

When asked what drew Holleran to film Missing, he responded “For me, I'm always attracted to movies and particularly any kind of projects that push technological boundaries, where innovation is involved, where you're on the bleeding edge of technology in the camera space, in the cinema world. I like exploring there, because it pushes my knowledge, it exposes me to new things and it makes me a better filmmaker. So, it was an instantly a no-brainer to work on a project that has great pedigree and also to be at the forefront of the largest screenlife movie of all time.”

Screenlife movies are a newer genre of films that tell the story from the perspective of the screens, whether that’s cell phones, computers or even security cameras. It’s part of a growing trend in production meant to help capture how much of modern day-to-day life includes these screens. While productions like RapSh!t have leveraged screens in their storytelling, Holleran believes that Missing is the largest screenlife feature to date. So what exactly goes into a screenlife movie?

First, Holleran shares what he aimed to achieve visually, “We want the camera to be able to move. We want the actors to be able to pick up the laptop, walk around and talk to it. We want them to be able to hold phones in their hands and walk around with them. We want to do a sequence from the perspective of an Apple Watch. We want to see things from infrared cameras. We want to do security angles and backup cameras and add all these different camera perspectives that exist in the real world, into the screenlife genre.”

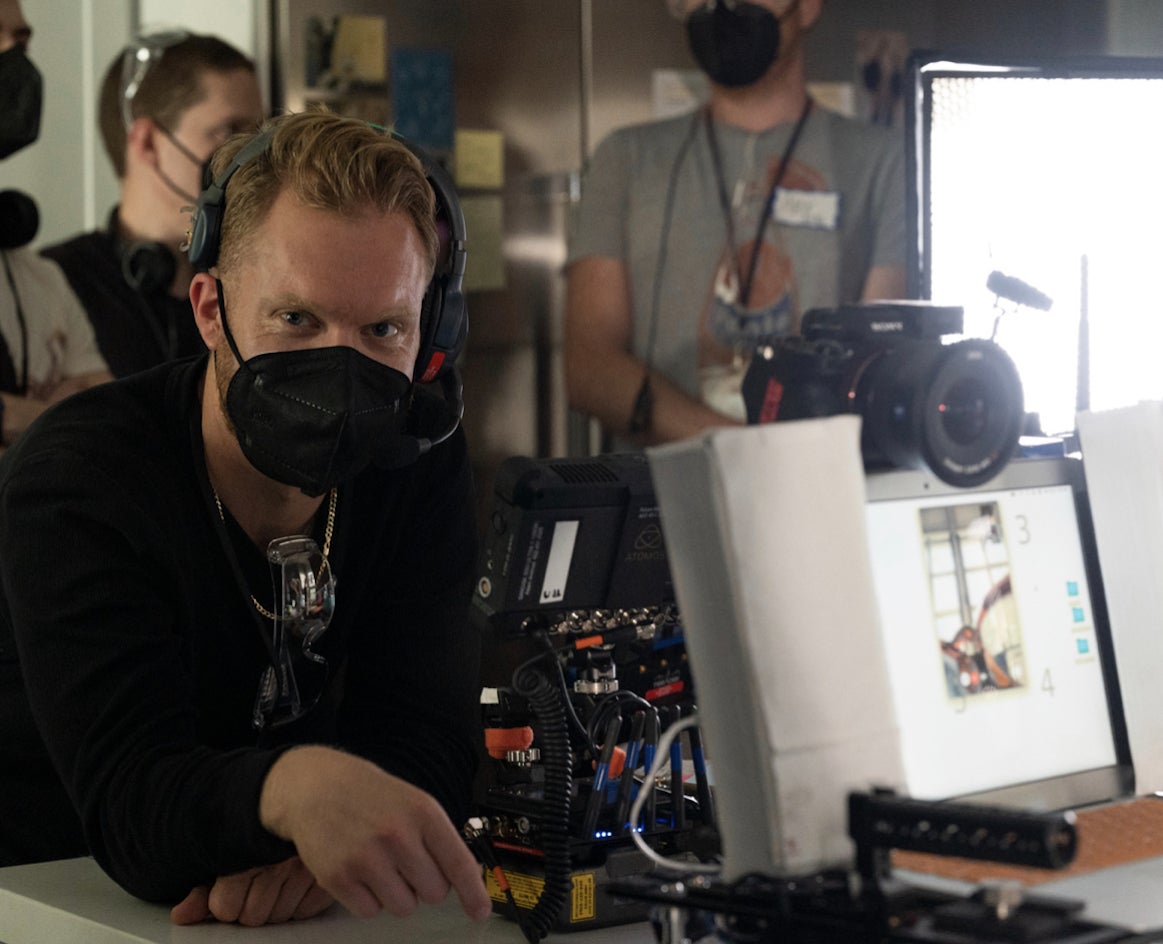

Next, came gear selection. After testing cameras for over a month, Holleran shares how he landed on a combination of the Sony A7S III and the FX3 as the main workhorses. “Suddenly it became quite clear, almost every single camera would not work for this movie. Most of the big bodies wouldn’t work. We needed something that shot low light. The Sony was the only one that would do it. And it was small.”

Unexpected Solutions for an Unexpected Plotline

From the trailer, we see footage from phones, laptops and more. Holleran shares the unexpected solution to making these shots look screenlife while using digital cinema cameras. The answer may surprise you. In order to maintain visual control of the image and recreate the look of the intended screen, Holleran had to rely on the actors to frame themselves – just as they would with a phone or webcam. “I didn't touch a camera through the entire production in terms of operating one. This time I had to coach the actors how to frame themselves. It required a lot of attention, in terms of talking them through where they needed to stand, why the lighting was the way it was, what part of the frame they had to look in, so it appeared that they were actually looking at the screen and not the camera.”

In particular, there was one shot that proved to be one of the most challenging scenes to shoot. Holleran shares how his team thought through this specific shot. “There was this one shot where Storm, the main actress, has to close the laptop and then open it back up. That proved to be one of the most challenging shots in the whole movie because I had a camera behind the laptop. It didn't close with the laptop. So, we had to create a new rig where the camera could actually move with the laptop screen, but ensure that it was not too heavy that the laptop would just close on itself.”

Holleran continues, “The laptop rig needed to actually have a working laptop where we could send video calls into the laptop so they could actually talk to another actor through the screen. Then we had to create this grid system on the laptop, with different numbers and boxes, so we could tell them, ‘Hey, you're looking in box one right now,’ because you're interacting with this larger computer screen in the movie so we had to be able to give them eyelines. We also had to be able to put another actor on the screen live and make sure they could type on the laptop.”

Using Autofocus for a Cinematic Application

Now, when you think cinema, you probably don’t think autofocus. Holleran explains how his team employed autofocus technology to enhance the storytelling and maintain a cinematic look for complicated rigs and while the actors were operating the cameras.

“We had to have autofocus lenses and a camera that accepted autofocus lenses, which is a cool Sony thing with the Alpha cameras and the Batis lenses. We could control the focus from an iPad. We could adjust focus with the slider bar while the actors were moving the camera around. For the laptop scene specifically, we couldn't fit focus equipment on this rig because it would get too heavy. So, autofocus helped out a lot in that setup,” explains Holleran.

When a Shallow Depth of Field Isn’t an Option

Being a screenlife film, Holleran didn’t have the ability to employ a shallow depth of field as many everyday screen perspectives share a wide open view. “I had to shoot at an F-12, F-14, but that meant that the lens was very closed down, which also meant I didn't get a lot of light into the camera. So at night, I couldn't shoot anything. It would be black, completely black. Even during the daytime, most scenes would be far too dark. The amount of lighting that I had available to me wasn't enough to brighten the scenes up. So, that became a serious issue before production.”

Continuing with the theme of adaptation and innovation, Holleran and his crew explains how he overcame this particular challenge using Sony cameras, “The only way around it was to shoot on the Sony Alpha 7S III and FX3 because they have that dual ISO. So we shot the whole movie at 12,800 ISO. I don't know how many movies have done that, 'cause it's pretty risky. Because when you're shooting at a high ISO, it introduces a lot of noise. So we had to do some testing and projection tests to make sure that the image would hold up on screen. It did, which is testament to Sony sensors, which I'm a fan of.”

Making Footage Look Like it Belonged in Real Life

You may be wondering, “How do you turn footage from a professional camera into video that comes from and iPhone, laptop, security camera, video doorbell and more?” Here’s how Holleran’s team achieved that transformation.

“We tried to pick lenses that looked like they belonged and match the perfect field of view of a backup camera for instance. So, we had to study footage from these devices. You wanted each camera angle to have the field of view and scope of what the actual real-life camera might look like. But we wanted to capture it in high quality.”

Now, don’t let the final product fool you in terms of image quality. Holleran used the highest quality possible to capture each scene. In order to make each view as real as possible Holleran opted to degrade specific images in post. He states, “A lot of that was done in visual effects. We would add noise and punch in on images in the edit. Banding and some warping and distortion would be added, so that it more accurately matched these real life cameras. Then in color, we took it to the next step in terms of, one, making sure they all matched and that they would look good in theater, but that they also felt like they were part of the real world.”

Holleran shares one of the most difficult creative challenges to shooting a screenlife film, “You had to flip a switch in your brain, from traditional cinematography towards tech innovation. You had to think about cameras in terms of how they worked in the real world, and less how you'd want them to look for a movie.”

Challenges = Growth

While June has to overcome countless obstacles in Missing, Holleran had to overcome just as many to create the film. Hear his thoughts after taking on the challenge of telling this story.

“This screenlife movie in particular taught me a lot about how to give up hands-on control of setting the shot, which is something that's usually very particular to the camera world. It was a challenging experiment for me to learn how to communicate better, to learn how to walk people through my process and what I'm looking for and why it's important. As cinematographers, being able to explain why you want to do something, how it's supposed to work and how to integrate other people into making that happen is extremely beneficial. This was a fantastic testing ground in that sense, for me and something that I think makes the cinematographer better at their job.”

When asked for final parting advice, Holleran shared, “The other thing I'd say, I think it's always good to challenge yourself to never shoot the same movie twice. It often takes me outside my comfort zone, but it also keeps things interesting and keeps the artistry fascinating for me, which ultimately makes this a lifelong learning process versus a paint-by-numbers job. I think that's where the artistry is.”