09-24-2021 - Case Study, Gear, Technology

Shot on VENICE: Pablo Berron Lenses Billy Eilish at the Hollywood Bowl for Disney+

By: Michael Goldman

Cinematographer explains how the singer’s “Happier than Ever” album was visually transformed into a stylized concert film.

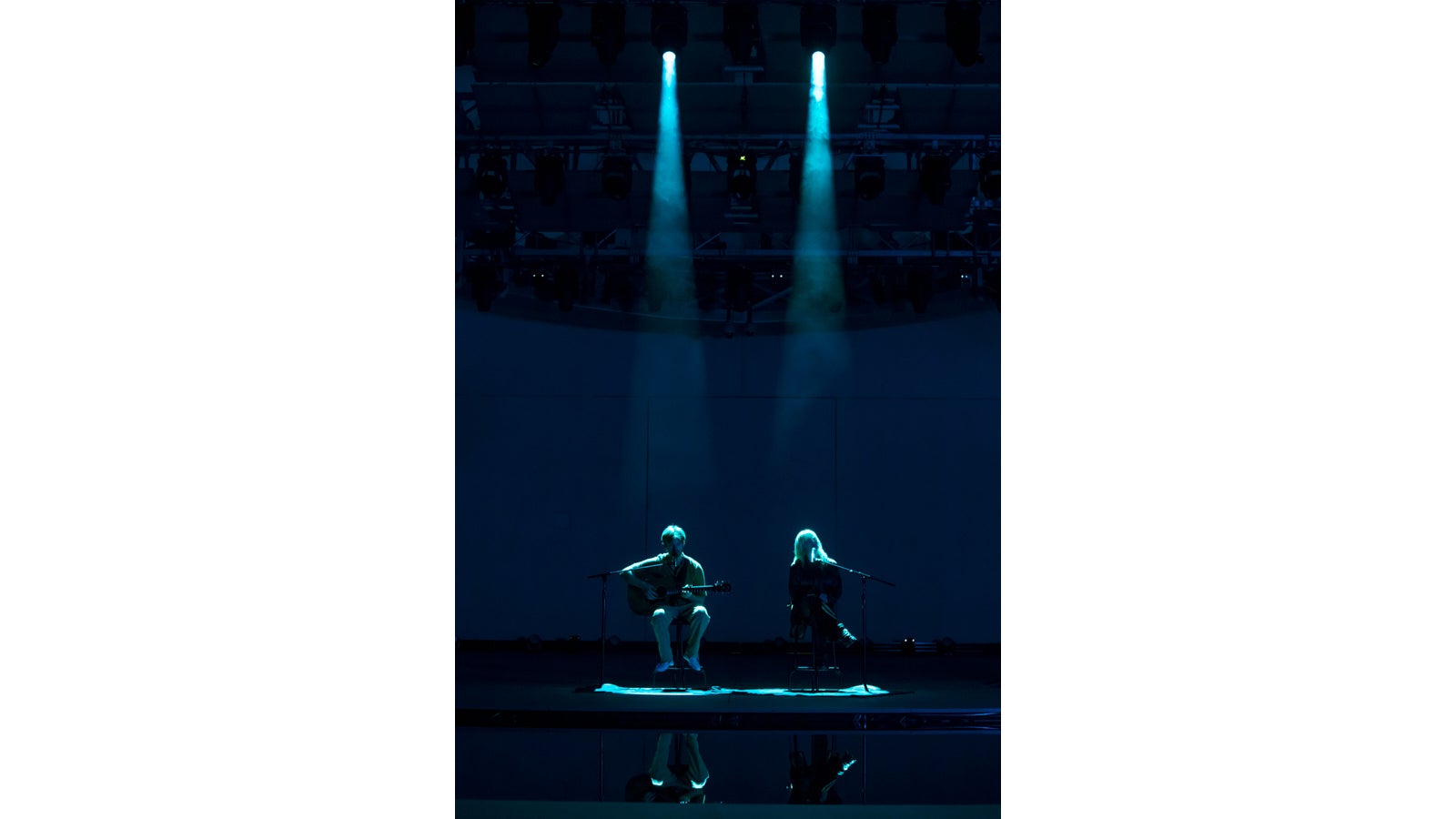

When cinematographer Pablo Berron was invited to shoot singer Billie Eilish’s new concert film, Happier than Ever: A Love Letter to Los Angeles, based on her studio album, “Happier than Ever” and now streaming on Disney+, he was overjoyed at the creative opportunity but simultaneously in awe of the project’s complexity. He was originally pitched on a film in which the young superstar would perform every song on her album in an empty Hollywood Bowl in a sort of classic Hollywood diva style. However, that approach quickly evolved, and in a big way. By the time the production got to the Hollywood Bowl for a week of principal photography this past summer, filmmakers were tasked with capturing Eilish singing 16 tracks accompanied by strategically designed lighting, blocking, and camera schemes thematically tailored to the specific nature of each song. During the shoot, she performed with her own band, solo, with her brother—songwriter/producer Finneas O’Connell—and on certain tracks with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, including famed conductor Gustavo Dudamel.

“It was a completely insane idea, once I understood the full scope of the project,” Berron recalls. “First and foremost was the schedule we had—about four nights with Billie and Finneas and the band, one full night with the Philharmonic, a day of shooting promos, and later, a few inserts. So, we were tasked, in a sense, with shooting four music videos every night.”

Further, as the concert’s style and aesthetic evolved, filmmakers had to become more innovative in filming each track compared to their initial plans.

“We originally had the idea of doing the whole thing as a classic Hollywood old-school type thing—an old-time feel to it,” Berron says. “But as we got more into the developmental side of things, we all realized Billie is a big rock star, high energy, young, and this is 2021. So we agreed it didn’t seem right that there would be one singular old-style palette for the entire hour-plus show. Instead, we decided to start classical cool, but eventually include [for certain songs] lasers and smoke, lights in the seats, put the performers in the seats, shoot crazy handheld stuff, and just really break the mold and take viewers on a journey from song to song, almost like different chapters in a book. So, it was grounded in the classical aesthetic of Hollywood, but in general, we tried to make it the coolest looking concert film of all time.”

Photo Courtesy Disney+

And to that end, after considering a number of acquisition platforms, Berron settled on shooting the movie with the Sony VENICE, shooting primarily 6K RAW (ISO 2500) in the 1.78 aspect ratio. His reasoning behind that choice included several technical and creative factors.

“Once we got into what the project was and how we wanted to shoot it, I realized that from a systems architecture standpoint, the Sony infrastructure would be helpful to our video engineers and the systems team,” he says. “We were going to have cameras roaming around, and we could fiber them into the main switcher—a lot of the type of multi-cam compatible stuff that Sony has been doing for so long, but which we haven’t seen much of with big-chip movie cameras. Over time, we had six or seven different video villages running at the Hollywood Bowl—a village for Sony, a village for her record label, a village for Billie, one for the band, for the sound team, the lighting programmer, and one for the camera team. We also really wanted to take advantage of an empty Hollywood Bowl, where we could put cameras anywhere we wanted—we could use Technocranes and drones and things, in addition to Steadicam and handheld. In that kind of environment, you normally wouldn’t be able to use a lot of angles, because cameras would obstruct the audience view and you can’t have drones flying over people’s heads. But in this case, with the Bowl empty, I thought we could move the camera in ways that nobody had seen before in a live environment, in a venue of that size.”

Thus, with VENICE being a dual-ISO camera, Berron emphasizes that having the extra speed of 2500 ASA “was huge” on a project like this one. And the other key need was for seamless remote control and communications. Digital imaging technician Dan Skinner says the VENICE system “allows for great remote-controllability,” whether working with a tethered or a wireless camera.

“[Video engineer] James Coker added MultiDyne fiber backs to our cameras, so that with a single fiber signal, we could get tower, video send, video return, timecode, audio, and ethernet from our tethered cameras,” Skinner explains. “We had four cameras tied into that fiber system. We also had the ability to change ND by the click of a button remotely from [a green-room/office on the Hollywood Bowl campus where the DIT was based], which was awesome. For most cameras, I would set things to the base ISO 2500 and then rate it at 2000 just to kind of over-expose it a little bit so that we were not always reaching maximum exposure and had a little further we could go if we needed it.”

Skinner also set up a mesh WIFI network at the venue so that other cameras could go wireless while filmmakers still retained control of them. Wireless cameras were rigged with Wave Central’s cineVue COFDM HD broadcast transmitters, which permitted Skinner to control handheld cameras wirelessly while he controlled tethered cameras via fiber connection.

The DIT says the production also placed an array of four antennas on stage, and four more pointed into the stands so that a solid picture was maintained no matter where the performers or the cameras wandered at any given moment. He also provided Berron with a wireless 22-in. portable OLED monitor with a QDR receiver on it, so that he could always have his own immediate view no matter where he was in the venue.

Photo Courtesy Disney+

The other key weapon in Berron’s arsenal was a VENICE-specific base look-up table that was crucial in “finding” the look for each song along the way during production.

“I had done a VENICE project not long before, and my friends at [LA-based post-production house] Company 3 had given me some look-up tables designed specifically for the VENICE,” Berron explains. “As soon as I saw them paired with this camera, I thought this was the best, most filmic look I have gotten from a digital camera. I kept that in mind when I got this project, and felt confident we could get a filmic, pretty image.”

With a small amount of contrast and color tone tweaking, that became the project’s base LUT. Skinner emphasizes that during the course of filming, he would only modestly adjust certain takes using Pomfort’s Live Grade system. Mostly, filmmakers preferred to view playback from different cameras (six total were rolling at any given time), pick the particular look that pleased them the most, and then later match other cameras to that.

And then, of course, the VENICE’s full-frame 6K sensor was extremely appealing to Berron for a quick-moving project like this one, along with the camera’s ND filtering capabilities.

“I felt that since we didn’t know all the specifics of the lighting environment, shooting at 2000 ASA would be like a dream, plus I could have [Skinner] control cameras remotely,” Berron says. “In fact, if the lighting programmer couldn’t quickly change a master fader, the DIT could change ND in one-stop increments at the press of a button, something no other camera is really able to do, and which is a brilliant feature.

“I also was planning to use a huge array of lenses, far more than I normally would on a typical music video, commercial, or movie, and this was one of the few cinema cameras that can give you Super 35 optics with a center crop and still give you a 4k output.”

In terms of those lensing choices, Berron explains that the original plan to shoot the film in the anamorphic format to enhance a filmic sensibility also evolved. After some testing, he says, Robert Rodriguez—the film’s co-director along with Patrick Osborne—pointed out that while a widescreen cinematic sensibility was desirable, the format didn’t lend itself to highlighting the historic Hollywood Bowl architecture in certain compositions, particularly the Bowl’s unique arches. Thus, including the very top of the frame became important to the show’s overall aesthetic.

As a consequence, the approach was altered to shoot a full spherical 16x9 frame. And so, to achieve both of those goals, Panavision worked up packages of several different types of prime lenses, zoom lenses, specialty lenses, and optic attachments designed to weave an anamorphic, film-style sensibility into the tapestry, despite the use of spherical lenses. Berron says A camera/Steadicam operator Orlando Duguay utilized primes 100 percent of the time during the shoot; B camera operator Michael Merriman used a mixture of primes throughout production off a 50-ft. Technocrane, and also Fujinon Premista zooms and 15-30 P70 Primo zooms for scenes involving the LA Philharmonic; a second Steadicam/D camera also utilized Premista zooms; and, according to Berron, “C and E camera were almost always on either expanded 11x PV Primo zooms or PV expanded to 3:1, sometimes on long primes with doublers too, while all handheld work was done on Primes.”

Photo Courtesy Disney+

In particular, to find that sweet spot between the anamorphic feeling he was striving for and achieving a full frame, Berron credits Panavision for providing anamorphic streak filters, specially customized by Panavision, that fit onto the front element of a spherical lens to create a more anamorphic, flared and distorted sensibility.

Berron explains that another key goal for camera style revolved around making sure that viewers felt like they were on stage with Eilish as much as possible.

“I didn’t want the camera really far away on long lenses like you do in normal concert films,” he says. “When you can be on stage with the performers, it creates a really cool connection, especially with a performer like Billy Eilish, who is so aware and so present and so good with the camera. Her performance is actually tied into where the actual camera is, in a sense. When the camera is near her, she can almost dance with it. So along those lines, it’s important to give a shoutout to our Steadicam operators. Our main Steadicam operator [Duguay] was a magician in terms of being reactive and flowing with Billie—they had a really great connection. And it was the same when I was doing handheld with her. It gave the whole thing a sense of intimacy. We quickly discovered that the closer we could get the cameras, and the wider the lens, the more spectacular and immediate the experience became.

“With the Philharmonic sequences, however, that was a bit different. It was more of a multi-cam space with them, just because we needed to cover so many more performers and there were so many more variables. So, the cameras were a little further away for those songs.”

In terms of lighting, Berron’s team worked in close collaboration with Eilish’s theatrical lighting director, Tony Caporale. He designed color palettes and live stage lighting effects for each song in order to create the correct visual atmosphere for each of them. Berron and Caporale then worked closely together to make sure those lighting schemes would work for cinematic applications.

At the end of the day “a big mix” of different lighting instruments were utilized, Berron says. Caporale primarily programmed the recently upgraded Hollywood Bowl rig, and his designs were supplemented by a wide range of motion-picture lighting instruments. Those ranged from Maxi Bruts in the background to Mole Richardson 10Ks, Arri SkyPanel 360 units, along with other LED units, Jem Balls, and more.

“Theatrical and [cinema] are two very different styles of lighting,” Berron explains. “With theatrical lighting, when you key light the performer, you typically have the lights pretty frontal and flat on them to be able to let people see them from far away in the audience. In order to not have lights in people’s faces, you use pretty steep angles, and the lights are often really high up on towers or they are lighting the talent from high up on stage. But except for atmospheric stuff, that kind of lighting for performers is different cinematically. We wanted lights close to eye level, a lot of diffusion, and big, broad sources—things you don’t typically do in a live show.

“Tony told me he understood this was for camera. So, he designed a color palette and what the light rigs should be doing for each song, but then we went through it song by song, second by second, minute by minute, and we figured out where to adjust. What I ended up doing most of the time when the camera was close on Billie was turning off any light that was lighting her from the front, and we just went with all the back light. If I needed a bit of fill, my lighting team designed some fill and RGB color stuff for her. So, there was a number of little things that we did to accent the theatrical stuff. Sometimes, we would put big lights with big diffusion frames, and get them close to her. Sometimes, we brought in old movie lights and put them on the stage and used them as key lights from the floor, rather than top lighting.”

Berron adds that the production’s access to an empty Hollywood Bowl meant filmmakers could also take advantage of drone technology for some unique aerial views of the venue. “Flying a drone as close as possible to the seats, as fast as we can, as much as we can is something we otherwise never would have had a chance to do,” he emphasizes.

Aerial director of photography Sam O’Melia says that for key aerial shots, the project used a heavy-lift drone called the Alta-X, from Freefly Systems. That vehicle flew a Sony VENICE outfitted with a 14mm Ultra Prime lens and a Teradek transmitter, rigged to the drone with a Ronin 2 aerial gimbal—equipment provided by Beverly Hills Aerials.

The project also utilized a 50-ft. Technocrane and two Steadicams daily. “We considered all sorts of gimbals and stabilized heads, but at the end of the day, two Steadicams, two dollies, a couple of drones, and the Technocrane did the job nicely,” Berron adds.

The cinematographer then worked closely after the shoot with Company 3 senior colorist Natasha Leonnet to grade and master the footage, and he says their work together validated his choice of the VENICE camera system.

“Natasha even came to set a couple of nights and was impressed that we were pushing the limits of the camera,” he says. “We had the highest possible dynamic range, from zero IRE and black levels, in the deepest crevices of the venue, to the most riotous crazy highlights, to even seeing the lighting rigs themselves, to ending up with deeply saturated colors. It was so creative with her help. My favorite song in the film, for instance, ‘Oxytocin’—the whole song is shown in deep, deep primary red, and it looks amazing. Billie was so close to the sensor for many of the songs, it was really impressive. I’ve never pushed a camera to such extremes before, and it reacted perfectly. I’ve shot a lot of live music before, usually in a more traditional way, but this was more complicated in terms of both design and how to execute it by several orders of magnitude.”