09-21-2020 - Gear, Technology

Matthew Duclos On Evaluating Used Cine Lenses

By: Jeff Berlin

A lens technician by trade, Matthew Duclos began working in optics under his father’s guidance at a very young age. His passion and technical aptitude for optical and mechanical design have led to a lifelong obsession with cinema lenses. Matthew continues exploring lenses of all kinds, consulting for a variety of lens manufacturers around the world. An associate member of The ASC and SoC, Matthew strives to share his knowledge and experience with the motion picture industry as a whole.

In this conversation, Matthew discusses a few things to look out for when evaluating used cinema lenses.

Duclos Lenses, Inc. is a family owned and operated business with decades of service knowledge and experience. As the premiere source for motion picture lens sales, service, and accessories – Duclos Lenses continuously strives to provide the absolute highest level of professional, personal lens service and repair to the global motion picture industry. You can visit their website here: DuclosLenses.com

Jeff Berlin:

Let's start with buying a used lens… what should we look out for?

Matthew Duclos:

The starting point should be where you're buying it from. You want to try and buy from reputable dealers. That should be your first course of action, but a dealer won’t always have the gear you want. So the next step is eBay or an auction site, and my number one piece of advice for that is to always look for auctions that have a return policy. If there's no return policy, it's a red flag that means they just want to get rid of the lens, that they don't want to deal with it. So my number one rule for where to buy lenses - buy from a reputable dealer and if you're going to eBay look for a return policy.

There are three considerations, three ballpark points, when evaluating a used lens - mechanical, optical and cosmetic. For mechanical, run the iris ring, run the focus ring, run the zoom ring, infinity to minimum focus, wide to telephoto on a zoom, open to closed on the aperture, to make sure everything's smooth and consistent, that there are no bumps, no snags, no loose components, you should feel a smooth action. You want to ensure internally, mechanically, everything is performing the way it should.

Jeff:

What if you shake it?

Matthew:

Exactly. The shake test, gently shake the lens and listen for anything loose or rattling around inside.

Jeff:

So what should you expect to hear, if anything?

Matthew:

That depends on the lens. If you're buying a relatively affordable still lens like a kit lens, you're going to hear something, it's inevitable. If you're buying a cine lens you should not hear anything. Sometimes you may hear the iris blades rattle just a tiny bit since they have to be a little bit loose to move freely, but if you hear something bouncing around inside, that’s not good.

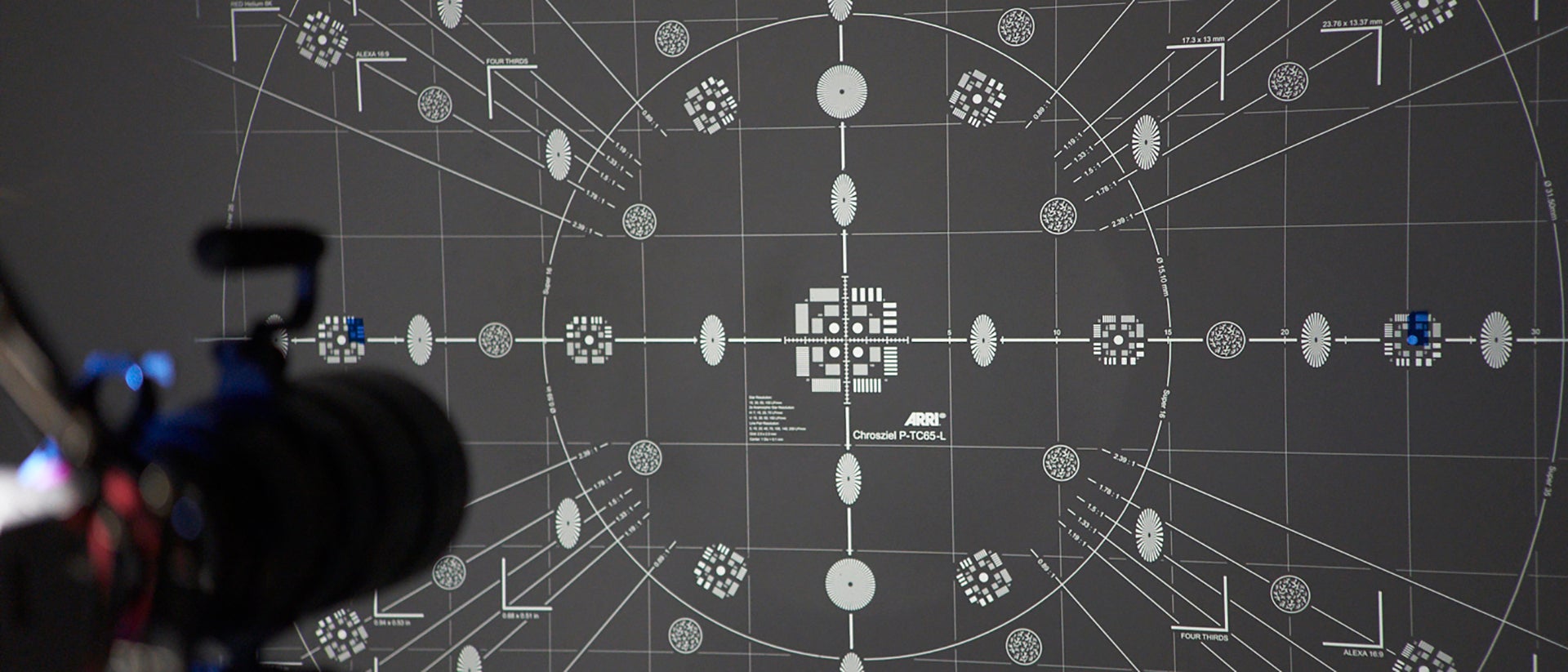

Optically testing requires specific equipment. You can put the lens on a camera to see what the lens is doing, but that’s not going to be scientific or objective. In terms of optics, you always want to put it on a camera as soon as you’re able. If you buy it from a brick-and-mortar dealer, bring a camera to the store with you. In terms of optics, you want to make sure that your image is what you’re expecting. But don’t expect a perfect image out of a used vintage lens. If you're shooting a focus chart and you're lined up correctly, you don't want the left side to be good and the right side to be soft or vice versa, or top and bottom, you want symmetry.

Lens mount wear with brass visible on right

Jeff:

What about an anamorphic lens, where you have softness all around and perhaps a sweet spot that's sharp.

Matthew:

That's fine. As long as that sweet spot is symmetrical. You expect that with an anamorphic lens, where your focus falloff is more dramatic outwards, but it has to be the same left to right, top to bottom. If it's not, that's a clear indication that something has been knocked out of alignment.

Jeff Berlin:

So focus falloff should always be symmetrical?

Matthew:

Always. By the laws of physics your lens is either spherical or anamorphic but focus falloff has to be the same no matter what, left to right, top to bottom. If it's not, then it's either manufactured incorrectly or it's out of alignment. There are so many tests that we do here at Duclos Lenses but I can't really recommend them to people who don't have a test projector or an MTF Bench.

The cosmetics of a lens can be very indicative of the quality of a lens. One of the first things I look for is the overall condition of the anodizing. If it's beat up and chipped and scratched you know the lens hasn't been cared for, so the physical appearance of lens tells us a lot. The other less obvious thing that I look at is the quality or the condition of the mount. Most photo lenses and some cine lenses have a still lens mount, and that mount is almost always made of brass with a nickel plating.

If that lens has been put on and taken off the camera a thousand times, that nickel plating wears out and you can see the brass color through the plating. That's a huge telltale sign, especially with vintage lenses, where if you see that color it means it's been heavily used. One of the things I don't really care about that people go nuts over is the serial number of certain lenses, which is kind of how you determine their age. One of the most specific things I tell people is to forget the serial number, forget the lens’ age.

For example, the old Leica R series is very popular. You can have an R lens that was produced in 1999 which is right around when they stopped making them, and whoever bought it beat the crap out of it and used it every day and didn't care for it. And you can have the same focal length, same design from 1989, 1970, whenever, that someone used very gently and cared for it properly. They properly stored it and it's going to perform much better than the lens that was produced 10 or 20 years later that wasn’t treated as well. So don't get hung up on serial numbers and production ranges and the date when it was made because that doesn't necessarily translate directly to a better or worse lens.

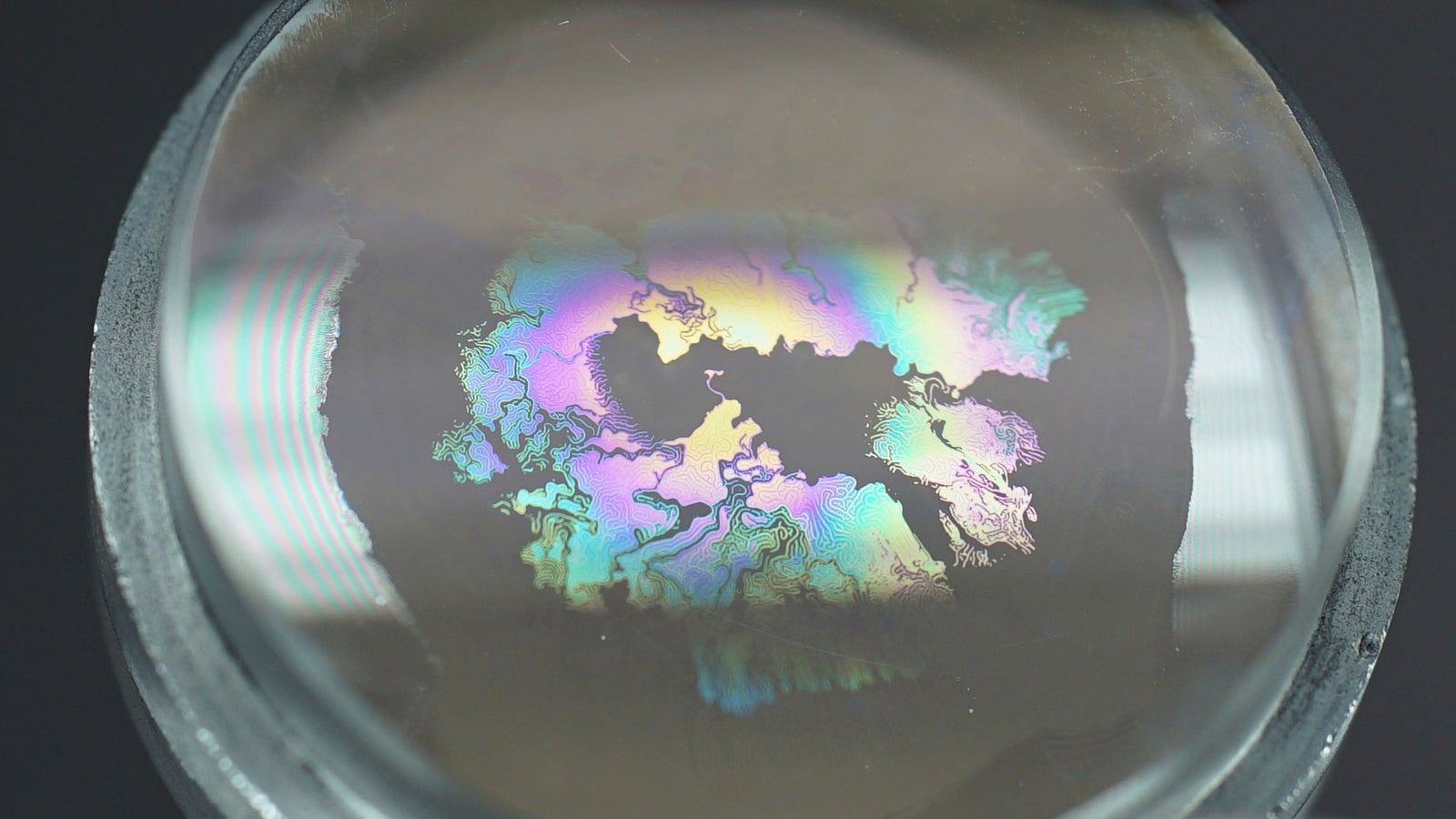

Lens fungus

Jeff:

What if there’s a fungus among us? What causes that and how do you avoid it?

Matthew:

Fungus is just like what you'd find in a forest. It grows in cool, dark, damp places. It's literally an organic fungus that grows on a lens. It's usually from moisture that gets trapped in between elements and it just festers and grows and spreads. To prevent it, just keep your lenses dry, store them sort of like you’d store wine, in a cool dry area away from moisture. If you're storing them in a cabinet or a case, put desiccant or silica gel in the cabinet as well. The easiest way to prevent fungus is to just take good care of your lenses.

Jeff:

If you find fungus, can it be cleaned it out?

Matthew:

If you find fungus early enough it can just be wiped off very easily. If fungus has been sitting on a lens for a long time it can etch into the coatings and then into the glass. At that point it's nearly impossible to get rid of it, or more accurately, you can get rid of the fungus but the etchings will still be there, so there is a point of no return in terms of fungus.

If you're buying a vintage lens and it has fungus, it's impossible to know when it started and how long it's been there, so buying that lens could be a huge risk, and it's a huge consideration because you don't know if it will clean off until you open the lens and try to wipe it off. Also, moisture doesn't always turn into fungus, sometimes you can just have moisture evaporate and leave stains behind. Those can usually be cleaned off pretty easily but it's something to consider. If a lens had moisture it probably wasn't well cared for so keep an eye out for moisture spots as well.

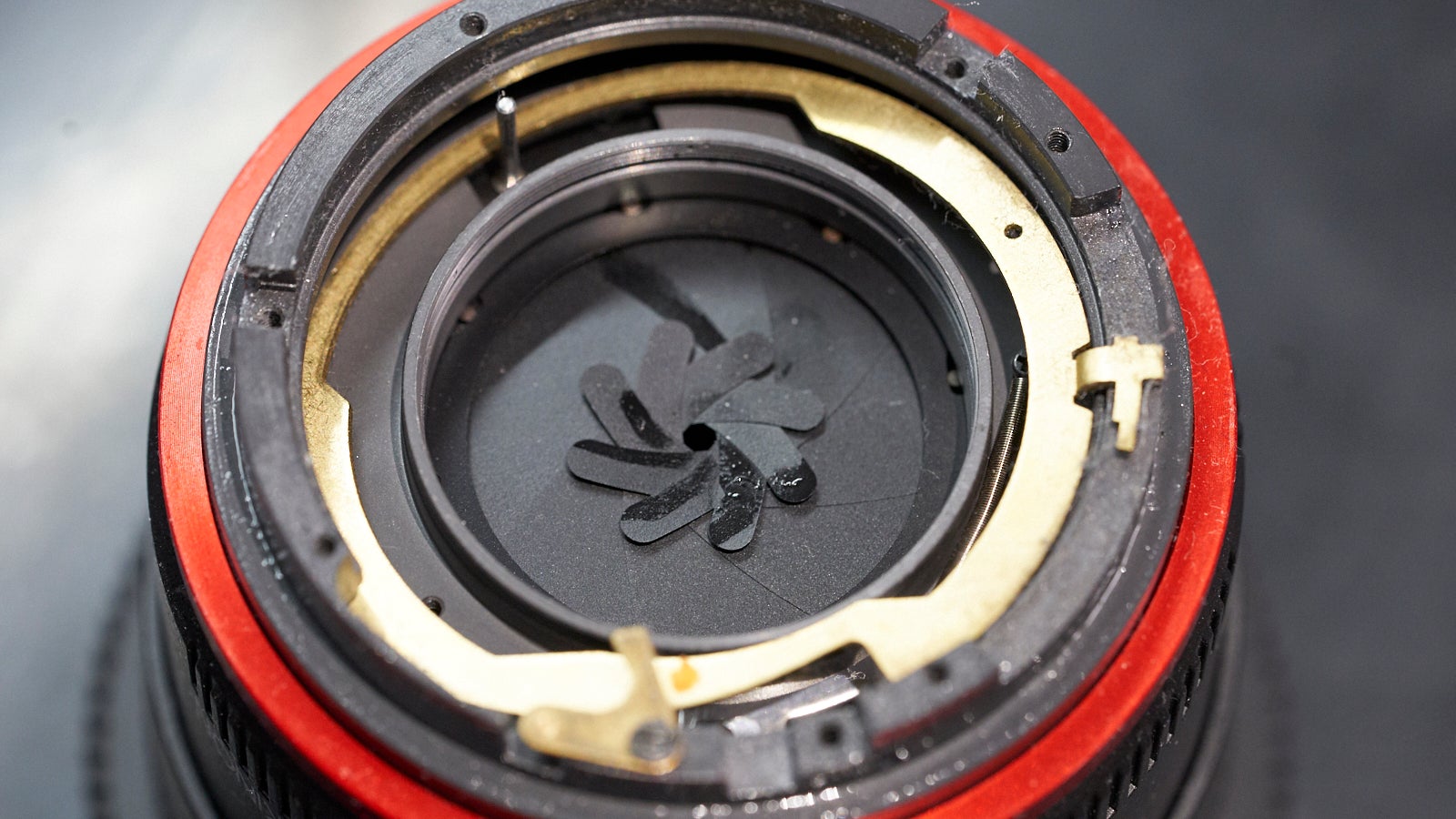

Another thing to look out for is oil. It's not uncommon in vintage lenses to find oil on iris blades, which again doesn't mean it was abused, it just means it wasn't well cared for. Either the lens was exposed to severe temperature fluctuations or it was never cleaned properly or maintained well.

Oil on iris blades

Jeff:

Would this oil have leached out from the mechanism?

Matthew:

Yes, exactly. Every iris has to have lubrication on the mechanical components, not the blades themselves but those mechanical components are still open to the blades. So the oil from the grease can break down, turn more fluid and seep onto the iris blades. And if it gets bad enough they'll literally drip onto the glass and that's when it becomes a problem. If those fine iris blades get oil on them, the oil can become sticky and the blades won't actuate correctly

Obviously, scratches, pits, anything abrasive you always have to watch out for. It's not as bad as some people may think because a lot of times they'll never see the result, especially on telephoto lenses so I'd say this is a little more critical if you're buying a wide angle lens. For example, consider a 14mm, because your depth of field is so much deeper, a significant scratch or a pit or fracture or anything in the glass could show up much easier than something on a 180mm lens. So this is somewhat dependent on your focal length and the speed of the lens, and it’s another thing to keep an eye out for when you're looking for used lenses.

Lens corrosion

Jeff:

What about when you see dust among the elements?

Matthew:

Same scenario as scratches. More often than not it'll never show up if it's not too severe but again, that's an indication of how well or how poorly the lens was cared for. If the lens is full of dust, it obviously wasn't kept well.

Jeff:

I have a friend who lived in Hawaii and when he did, he kept all his electronic devices in a dehumidifying cabinet because of the salt air, so what about salt air?

Matthew:

Salt air is a concern as it can corrode the metalwork on lenses. If you live in that kind of environment, like in a tropical area, salty air, or where the moisture level, the humidity is super high, having a dehumidifying cabinet is like using a desiccant but taking it to the next level. Such a cabinet is probably not needed unless you live in such extreme conditions but again, even that is not too uncommon. We have customers in tropical climates around the world and they struggle with this all the time.

Regarding vintage lenses, the mechanical design of vintage lenses isn’t as robust as a modern lens, so that’s something to consider as well. The focus end stops, where you're going from infinity to minimum focus, or on a zoom, the stops going from wide to tele, may not be as crisp or as defined as a modern lens. Vintage lenses can feel a bit mushier, a little softer at the stop. Sometimes it's just because they didn't have a physical stop, where they just literally ran out of threads and you jammed it to the end. Or sometimes there's just a difference of materials, but in a newer lens you're going to expect defined, firm stops at both ends of travel.

Oil between lens elements