06-04-2021 - Case Study, Gear, Technology

Rebuilding Theater: “Waiting for Godot” Helps a New Media Emerge

By: Suzanne Lezotte

Sony Partners with The New Group to Provide Cameras and Services in a Remote, Worldwide Production.

The biggest lesson every industry had to learn over the past year with the pandemic was how to pivot. That was no exception for the world of theatre, which came to a screeching halt like everything else, but with no date in sight of when they could pick up the pieces. For founder and artistic director of The New Group, Scott Elliott, his personal investment in theatre was a lifetime commitment. Yet the downturn of the pandemic made him rethink what he was doing, in an effort to salvage the theatrical world. “I have a background in filmmaking and friends in that world, so we decided to make a shift and explore what we do as a theatre company in an experimental way,” he began. But when his friend, actor Ethan Hawke, called him and asked him to read, “Waiting for Godot,” he initially resisted. “Then it struck me as the perfect quarantine/isolation/pandemic play where people are essentially waiting, day in and day out, for their lives to get better, and I began to see it as a film. The play is about how to get each other through another day, and that resonated with me.”

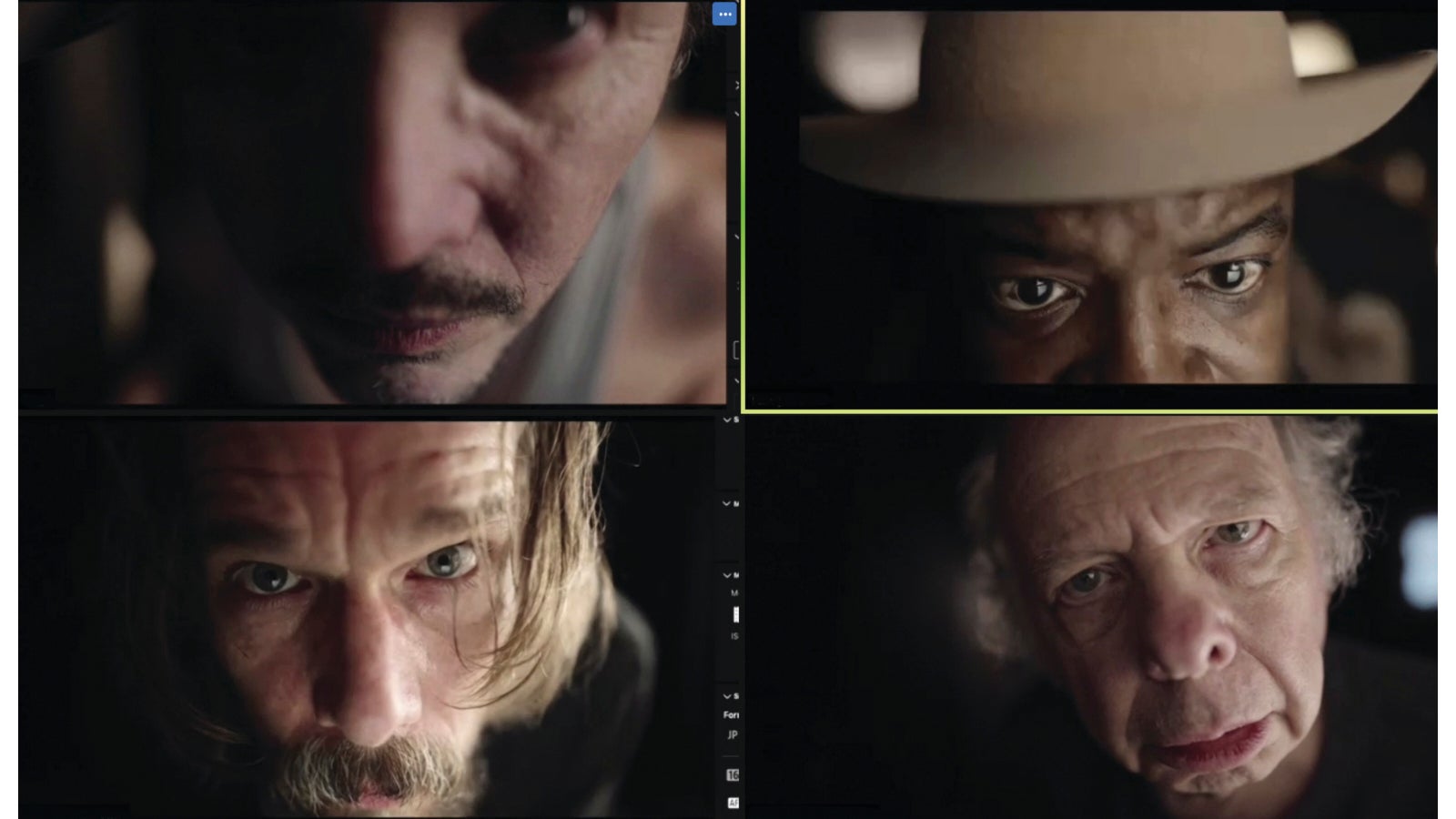

Photo - Monique Carboni

With the idea set in motion, Elliott ruminated on how to bring the concept to life. It would involve multiple actors, schedules, locations and crew, all coordinated remotely. It was about this time he met cinematographer Kramer Morgenthau, ASC, who he brought onto the project in the initial stages. They started last summer, exploring how to utilize zoom, “when we realized we were onto something,” and he began to gather the key creatives he would need.

Morgenthau had just finished a project for Netflix, “American Son,” which introduced him to the world of Broadway, and production designer Derek McLane, a board member of the New Group. “I happened to be in New York doing some reshoots, so I met with Scott,” he explained. “What struck me is that he and his company were fighting for a way to not only survive, but to keep sharing theatre with the public in some way, without the restriction of not being able to perform in a physical theatre,” he explained. What drew Morgenthau to the project was, “the play and Scott’s passion to keep creativity alive during this pandemic. There was also my own desire to stay creative and push myself in a new direction.” Morgenthau admitted that there was a need to stay relevant “in a time when everything is turned upside down, and yet there are all kinds of new technologies available. I wanted to try something different and test the limit of what we define as cinematography in this new space.”

The project was intended to be completely remote, and with that in mind, Elliott began to select his team, including producer (and writer) John Ridley, editor Yonatan Weinstein, who was riding out the pandemic in Tel Aviv with his family, the DIT team from Pixel Picnic, Damon Meledones and Ian Edwards, who were based in Baltimore and Brooklyn, and Morgenthau, who was in Los Angeles. Lastly, colorist Peter Doyle, Postworks, Technicolor, joined the team. Together, they began an endless stream of zoom meetings to coordinate. The actors who jumped on board included Hawke in Brooklyn, Leguizamo, from his hotel in London, Wallace Shawn in Manhattan, and Tariq Trotter in New Jersey.

Photo - Monique Carboni

Another key element for Elliott was to enlist a production company called Mila Media, whose function was to help with organization, given the remote locations of the team and actors. “They organized the shoot, and post, staffed the technicians and helped set up all the technical aspects,” said Scott. “They really nailed the end-to-end workflow.”

With the show starting to come together, Morgenthau began testing cameras, settling on the recently introduced Sony a7S III “I’ve never done remote production before, and none of us fully understood what that meant. It was a big mash up of zoom, theatre, and filmmaking,” he said. “My goal was to make it immersive through photography and Derek’s production design.

The Sony a7S III literally blew the doors off the other cameras we tested.” Elliott agreed. “The depth of field is so incredible, it’s like a work of art. When we put together all the cameras in the edit, it was like five worlds existing on the screen at the same time.” Morgenthau used Sony G-master lenses, the 24mm f/1.4, and each of the actors was shipped a camera, a lens and a color-coded kit. “We used the auto focus on the cameras, especially when we saw how responsive it was, and so intelligent that you could tell it what to find. It’s not a replacement for focus pullers, but it’s a really interesting way to work with new technology, given the parameters we were under. The actors were leaning ten inches away from the lens and it was 100% sharp.” After two weeks of testing the camera and lens, Morgenthau was certain it was the right tool. “I was able to do a deep dive into this camera; it’s a cinema-worthy camera you can hold in your palm. The low-light sensitivity and auto focus, especially shooting my kids, is leaps and bounds above what I have seen.”

Along with Sony cameras, the production was able to utilize Ci, Sony’s professional media cloud service. “It was a completely remote production internally,” explained Morgenthau. “We were sharing files around the world and needed a way to share these files with the editor, Yonatan, who was in Israel. It was super easy to figure out; very user friendly.” Weinstein agreed. “It’s a great solution which saved us a lot of time in terms of delivering the footage from the shoot to me, and getting it set up as an Avid project.”

As production was about to begin, one of the worst storms hit the Northeast, and Fedex and UPS were completely shut down, which delayed the camera equipment. With one day for setup, “our technical was hell, with snarls around Wi-fi, since we were using everyone’s home Wi-Fi to communicate and watch the cameras,” explained Morgenthau. “We were controlling the camera by tethered remote -- from camera to laptop, to another computer -- while one of our DIT’s, Damon, was working from his basement in Baltimore, and another DIT, Ian, was at his apartment in Brooklyn, and our sound mixer was in his apartment.” Elliott agreed. “Everything that could go wrong, did go wrong. We had four days to shoot and we lost a day to technical errors, because even though the actors were doing what they could, it was a learning process for them. They had to change their own battery in the camera and work with the earpieces for sound. Luckily, we had Mila’s technicians who helped them troubleshoot.”

Photo - Monique Carboni

Morgenthau found his biggest challenge, “was the remote lighting. Controlling the lights over the Internet, and building lighting cues by remote, was tricky, so I kept it to an absolute minimum, shot with one camera, one lens, and a handful of lights that were controlled by DMX.” He shot mostly at 3200 ASA at f/1.4, “which was super low light, less than one foot candle. The camera is super light sensitive. But we also went to 1600 ASA for a candlelight session, which was magical, using just one or two candles as a source. It was a game changer, and the autofocus still worked in that low light level.”

For the team at Pixel Picnic, Meledones and Edwards, whose company specializes in creating bespoke workflows for complicated productions, they were familiar with other Sony Alpha cameras, namely the a7S II, but this was their first time using the Sony a7S III, as well as Sony’s Ci platform. “Having the Sony team, led by Michael Potts, available to answer our technical workflow questions regarding the camera and the SDK was really helpful. It allowed us to have a level of control over the camera remotely, which we needed so the actors’ only responsibility was changing batteries, changing media and turning the camera on. Another big difference between the a7S II and the a7S III, was the Imaging Edge remote, which let us adjust the ISO, the shutter speed, the aperture, the auto focus mode, and tune the specific auto focus settings. Being able to do all of that remotely freed up the actors to concentrate on their performance, rather than the technical aspects of the production,” explained Meledones. With Ci, “the platform was mature enough that it was easy to use the advanced features to upload camera original files (XAVC HS format)

quickly, while at the same time making that footage accessible to the rest of the creative team, without them have to learn any special software or specialized techniques.”

During the first day of shooting, the DIT team established a baseline look that was applied to all of the cameras. “We used Sony’s VENICE S709 LUT, and made some color and saturation adjustments on top of that. That became our show LUT, so to speak; we didn’t do any individual adjustments from scene to scene, simply because of the short amount of time we had to shoot the project in.”

The team was also able to help Morgenthau dive into creative options. “Because this is a play and it has a linear timeline, Kramer really wanted to explore the ability to have synchronous control of the lighting at all five of our shooting locations.” After researching, “we developed a solution that allowed us to use a theatrical lighting system as a bridge across the Internet to work in all locations. We now had a lighting cue that allowed color and lighting changes to happen in sync with each other, despite everyone being on different time zones.” This meant everyone had a key light, a white muslin bounce, “and we had practicals we could remotely control; as well as the levels and on and off. Each location also had a faux window, with a remote-controlled lighting unit inside of it.” For Pixel Picnic, the underlying technology was DMX, using a protocol called Art Net, which allows you to send the DMX control information over an Ethernet network. “We combined that with our remote control implementation, and we extended that throughout the world. Essentially, we were using the same kind of technologies that we use on a stage, all in one location, but we were able to extend those imaginary cables through the Internet.” For Meledones, the most challenging aspect of his job on this project “was to balance between having the best technology, with keeping things easy to manage for the actors, especially when they had to set up the equipment themselves. The blizzard that happened was a challenge we didn’t expect, because it meant we had to remotely connect to the systems that were at our office, from home, so we could at least do the software side of our prep.”

Photo - Monique Carboni

For the Pixel Picnic team, they relied on Ci for communication among the team. “We really loved our experience with Ci. The built-in integration with IBM Aspera was a big boon for us in delivering footage, especially from London, where John was. With Yonatan in Israel, being able to move files around internationally in a timely manner was key,” said Meledones. “The email notifications we got when uploads were finished allowed us to spend a little less time worrying about keeping track of everything. It also freed up our capacity to work on other aspects, especially when everyone was wearing so many hats.” After filming was completed, “the ability to preview and set in and out points and download a transcoded proxy came in handy when there were questions about who did what on what days.”

Editor Yonatan Weinstein, who joined the team in November 2020, was excited to jump on board. “The idea of this play, in today’s society, felt more relevant than ever.” He was open to the idea of becoming involved before production started, due to the nature of the project, and the ability to communicate via zoom. Joining pre-production meetings helped him ascertain what his work would look like. “We were breaking the script down into blocks, discussing the best cutting points, and what shooting out of chronological order would look like,” he said. The Sony camera test reassured him that they would have a lot of options to play around with in editing. “Having an actual camera recording rather than using zoom gives us a lot more latitude in the postproduction process. On top of that, it was crucial to have Sony’s Ci cloud back up all the materials, which we could all access, without having to rely on physical flash drives to deliver the footage. We were really happy to avoid shipping drives internationally.”

Photo - The New Group Off Stage

As soon as they finished shooting, the team uploaded footage onto Ci, and he started downloading it. “I set up the project, linked directly to the source footage, transcoded it down using Avid DNxHD, and went to work,” he explained. Given that the project needed to incorporate seamless cuts ”in this zoom-like space, we wanted to introduce virtual glitches as transitions into the project, so we figured out the Boris FX plugin would be the solution for that.” Allowing for that part of the workflow was the reason they opted to finish the project in Avid, which is not the standard workflow (most are finished in Resolve). “Since I’m doing what would be considered online work, finishing in Avid made the most sense to us,” he said. Weinstein was happy to have Postworks Technicolor and Peter Doyle on the project, because “they have loads of experience and a good understanding of the technical process using Avid.”

Doyle explained that, “It’s very interesting, because you wouldn’t think of a Beckett play as very technical and layered, the way this was structured is very complex, with the full screens and editorial side of it. It’s been a great challenge.” For workflow, “we tried to break down how editorial had structured the project, and it became apparent that we needed to approach it as five DIs, almost in parallel, because of the split screen. There was a lot of treatment being added in editorial, as well as editorial jumps, so we came up with a workflow that was a little unusual.” They were doing all the grading in the Sony RAW, to build an efficient workflow, “and we used the Avid as the final finishing tool,” he explained. Morgenthau added that Doyle “is truly a color genius, and he’s also a photographer who shoots with Sony cameras, so he understood the nature of this project.”

Photo - The New Group Off Stage

The turnaround time for Weinstein to access the files was shorter than waiting for drives, which he credits with the use of Sony’s Ci, but he also believes some of that had to do with using the a7S III. When the Pixel Picnic team introduced shooting with the H265 codec, “to allow us to compress incredible resolution into really small files, I was initially concerned about the format – Avid had pushed out its December 2020 release for Avid Media Composer, which was the first to introduce native support for H265. I upgraded the Avid system prior to production and ran a few tests with Kramer to make sure the codec compatibility worked seamlessly. At the end of the day, it proved really helpful with the amount of data we had to upload to Ci. We had anticipated over 4 terabytes of footage, and ended up shooting less than 2.”

With the show now streaming, Elliott has only kudos for his team. “I had an A-team who brought their A-game and, as a director and producer, it made me relax. With everyone so emotionally committed and invested, it had the feeling of innovation and I am proud that we were able to do this. This feels to me like an intersection of art forms.” For Morgenthau, “this play really speaks about universal themes, isolation and loneliness, and waiting for something that may never come. It’s right up there in cutting edge ways to do art in the pandemic.”

Meledones summed it up as “a glimpse into what’s possible when we find new innovative solutions for doing things that have been born out of our collective experiences.” At the end of the day, Elliott said, “people came on board for the true spirit of it, which was to save the theatre.” Encore.

“Waiting for Godot” is now streaming at: https://thenewgroup.org/production/waitingforgodot/