09-15-2021 - Gear, Technology

The Realities of Shooting in Low Light, Even at High ISO

By: Alister Chapman

Alister Chapman is a regular contributor to SonyCine.com. Check out his website at http://www.xdcam-user.com.

With cameras like Sony’s FX3 and FX6 becoming ever more sensitive thanks to the latest Exmor-R back illuminated sensors and dual ISO capability, you would think that it’s now possible to shoot at incredibly low light levels and get great noise free (or at least very low noise) images. When shooting using S-Log3 on the FX3 or FX6, these cameras have a high base ISO of 12,800 but still some people seem to struggle to be able to get images they are happy with.

Having reviewed many examples of clips shot at these high sensitivity levels, I believe a lot of people are struggling because there is a bit of a misunderstanding about what shooting in low light really means.

Low Light vs. No Light

When talking about very sensitive cameras I often hear people comment that “the high sensitivity means you don’t need to worry about lighting.” This couldn’t be further from the truth. When we are talking about cinematography and the craft of creating beautiful or dramatic images, one of the key aspects of most shots is contrast. It is not so much about the amount of light that you have but the difference between the brightest parts of the image and the darkest.

When you have good contrast you can shoot video in very low light levels and have low visible noise. This is a frame grab shot with the a7S.

Before going further, one thing to point out is that the majority of the noise we see in an electronic camera comes from the sensor. And the noise the sensor produces doesn’t really change whether you are shooting in the dark or in brilliant daylight. But what does change is the size of the desirable signal we get from the sensor. When lots of light hits the sensor we get a big signal output, so the ratio between the noise and signal is better, the signal swamps the noise and we have a good signal-to-noise ratio. But if we don’t put enough light onto the sensor the image signal may only be fractionally greater than the noise so the noise appears large compared to the image information and we get a poor signal-to-noise ratio. We should also consider that no video camera is truly noise free. There will always be some noise no matter what we do and often a small amount of noise (even electronic noise) looks more natural than an image with no noise at all.

Take a camera out on a moonless night to shoot a scene and not only are the light levels very low, but because there is no distinct light source there will be very little difference between the brightest highlights and the darkest shadows. If you wanted to make the scene look more contrasty in post production, you would need to expand the range between the shadows and the highlights. When you expand the range in your footage, you will almost always exaggerate the appearance of noise. Stretching out the levels in a shot to make the difference between light and dark greater also increases the amplitude of the noise in the material and very quickly the noise can become objectionable.

Take the same camera out on a moonlit night and yes – your average illumination levels will be higher. But more importantly, the highlights illuminated by the moonlight will be significantly brighter than the shadows not illuminated by the moon. In all likelihood, there will be very little difference in the brightness of the shadows to the moonless night, they will be equally dark.

But now, when we take the moonlit footage into post production, because the recorded material has more contrast, we don’t need to expand the levels as much, perhaps not at all. And as a result, we do not exaggerate the noise that exists in the material and the shadows will look much less noisy as a result. Additionally, the viewer’s gaze will be drawn to the brighter parts of the image rather than the darker parts, and any noise that remains in the dark areas is less likely to be noticed.

Very often the reason why people struggle when shooting in low light levels is not because there isn’t enough light, it is often because there isn’t enough contrast.

To illustrate this I shot this simple test in my office. For both shots I tried to keep the amount of light on the back wall as close to the same as I could. The first shot used just the small amount of light that enters the office when the doors are closed, it is pretty dark. For the second shot, I added a tiny amount of light from left of frame to illuminate my face so that it is now marginally brighter than the background.

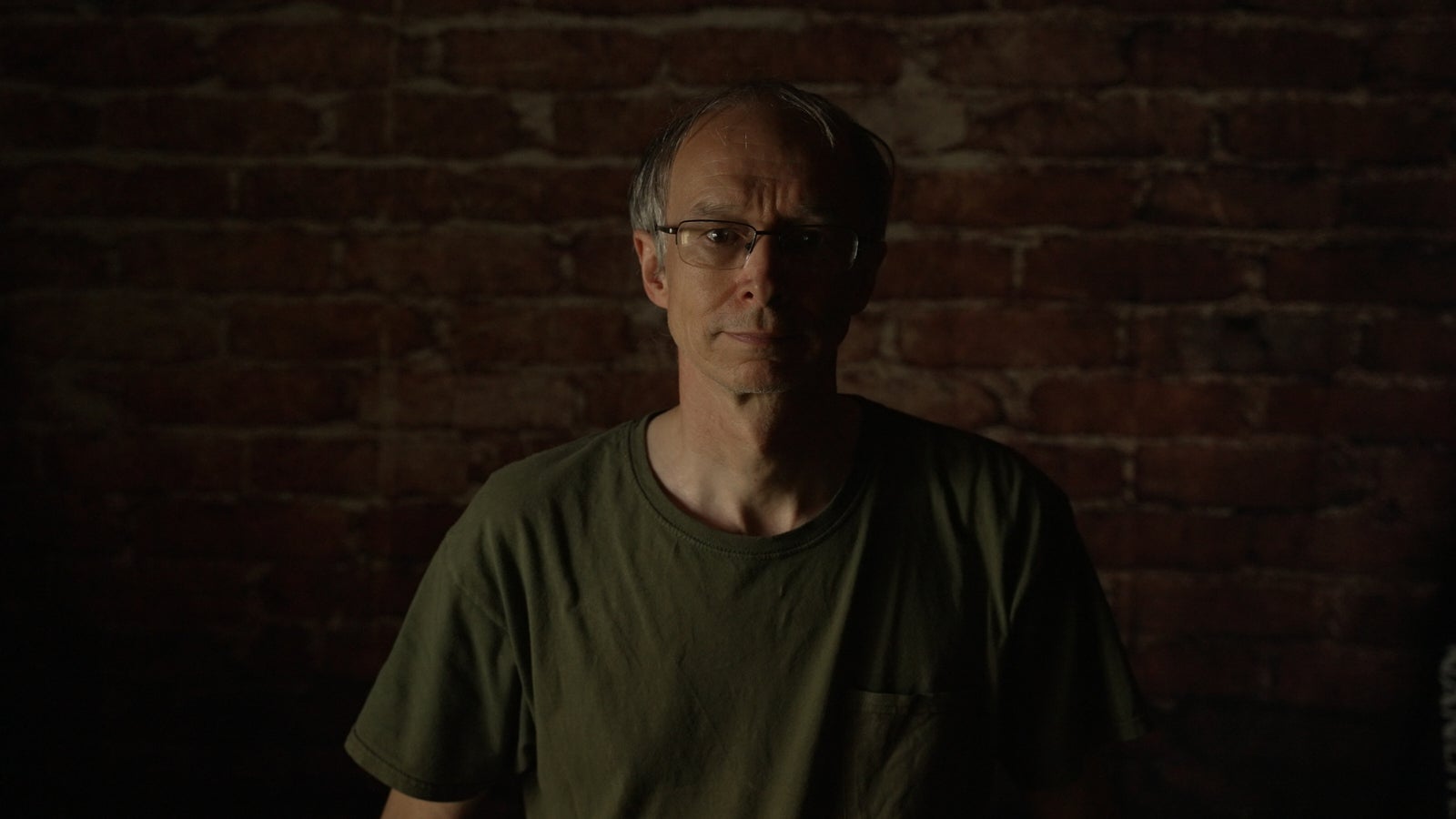

This, above, is the ungraded image without the added key light.

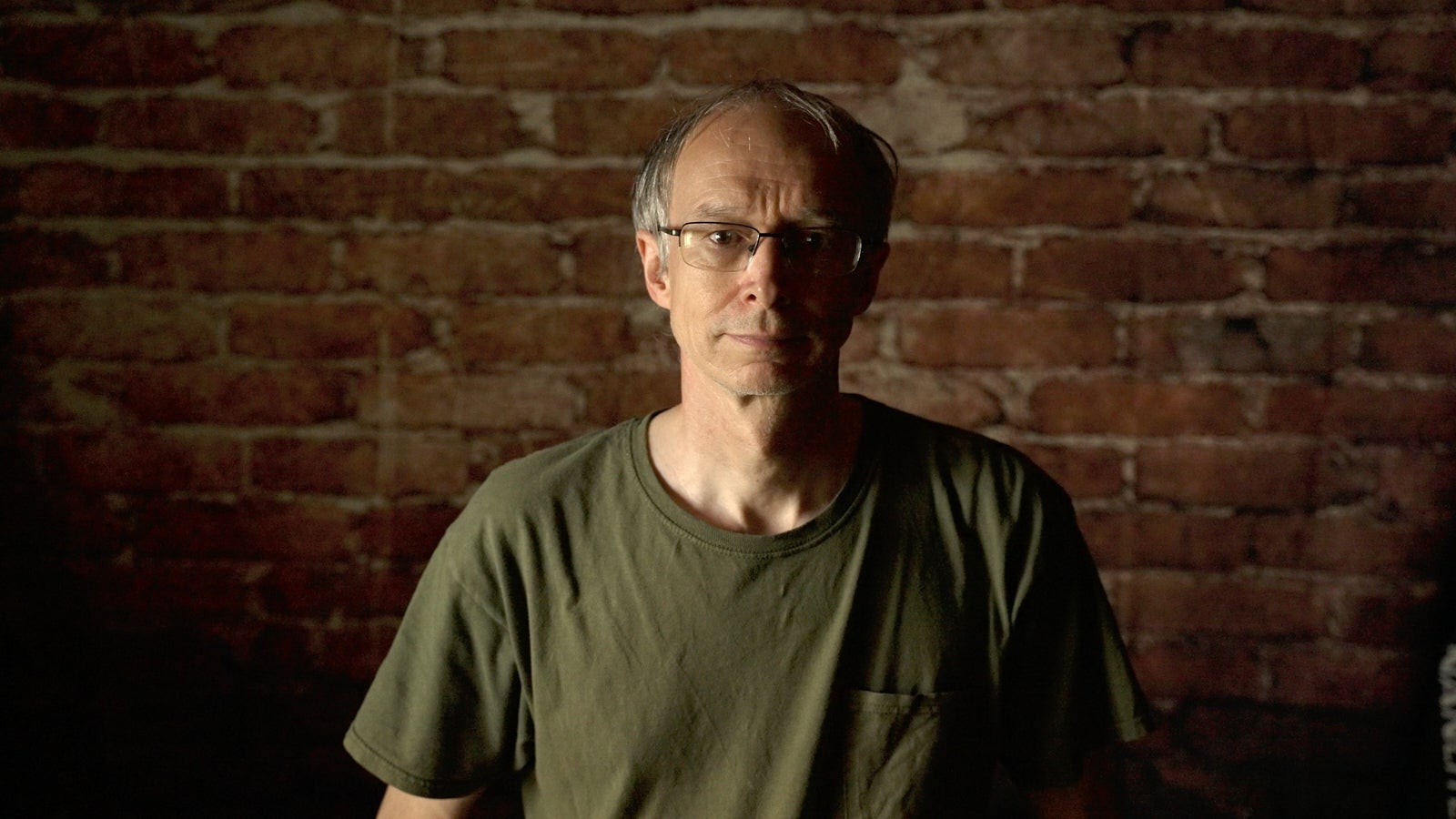

Above is the ungraded image with the additional key light, just adding a touch more contrast. But it is still dark, however even just this very small amount of added light has already improved this image.

Next, I graded both images bringing the levels up, trying to keep both images looking similar but now perhaps more acceptably bright, something many people might attempt to do on a similarly dark shot.

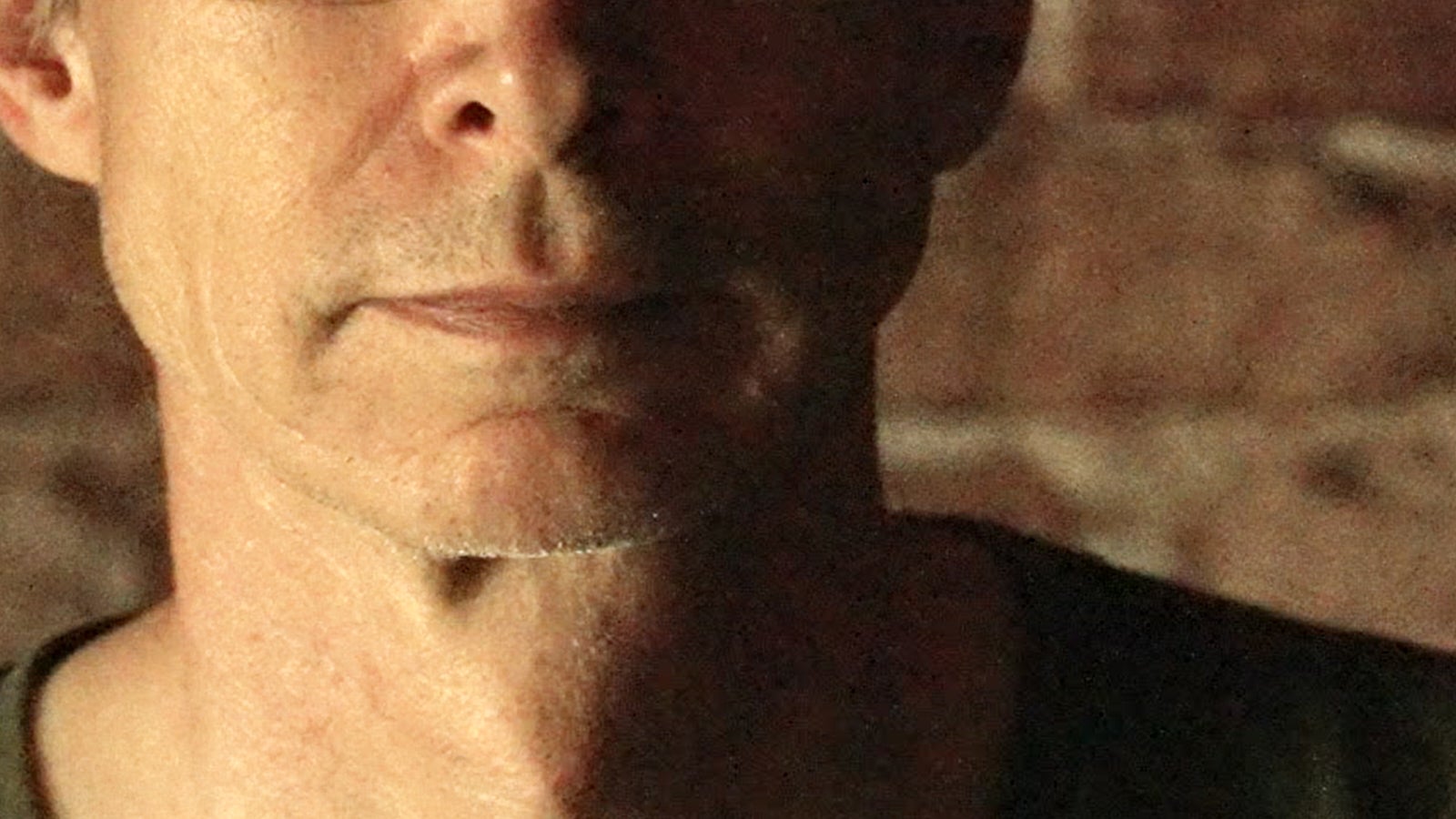

This is the shot without the extra light. As you can see it is possible to make it look better and more contrasty in the grade. But the noise in the image has become considerably more obvious.

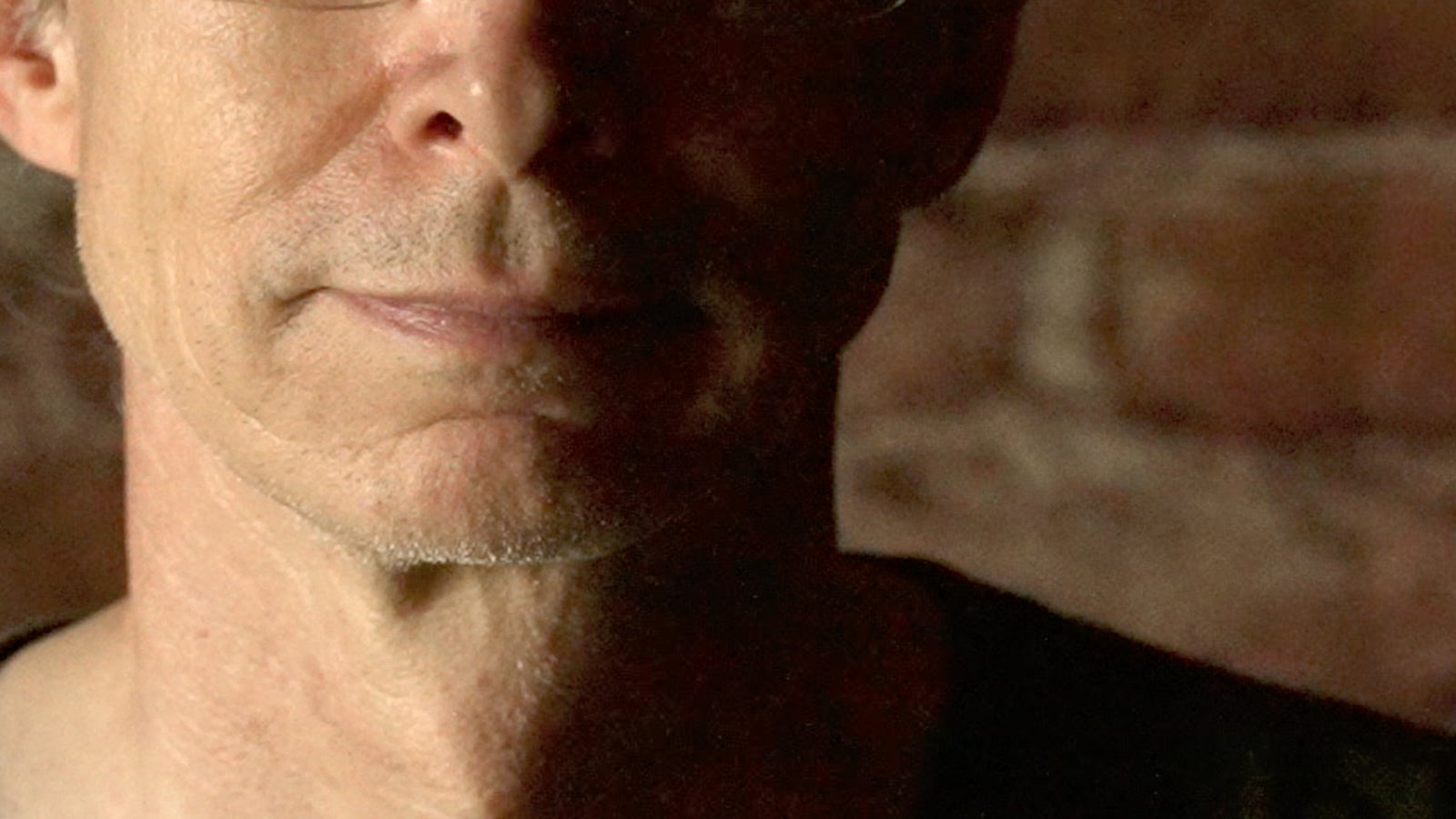

And this image above is the shot with that tiny little bit of extra light just on my face. It looks so much better than the unlit shot. Even though the light in the background and shadow areas is near identical that little bit of extra light on my face to increase the contrast makes a world of difference. This image isn’t noise free, but it’s a big improvement over the unlit shot.

If you zoom in to the unlit shot you can really see how noisy this has become. There are some very nasty, blocky noise appearing in the shadow areas of my face and neck in particular – yet these areas are actually little different to the lit shot. It is the process of stretching out the contrast to brighten the highlights in this image that has brought the noise up throughout the image.

As soon as you add that little bit of light or increase the contrast in the scene, you reduce the amount of contrast you need to add in post production and as a result the noise doesn’t become as ugly. The shadow areas, where the light levels are as close as possible to the same for both shots, look so much better when you don’t need to manipulate the contrast in post production. So when shooting in low light, think about the contrast. A shot with good contrast will generally produce a better result than one with low contrast.

I recently shot a short film where most of the scene took place in a large forest at night. This was a very low budget production and there certainly wasn’t enough money to pay for a big lighting rig to light the entire forest. But by lighting the tree trunks and other objects in the foreground with a couple of battery powered LED fixtures and providing the cast with very bright hand held flash lights, I was able to create sufficient contrast that you could clearly see the characters in the story, and it is obvious that they were in a forest at night. There really wasn’t any need to start lighting the trees off in the background. Perhaps without the lights there would have been enough light to see the faces of the characters, but they would have lacked the contrast. I also used smoke to allow the handheld flash lights to create beams of bright light. It’s the contrast that makes these shots work, the small but bright highlights allow the shadow areas to remain very dark and as a result, noise free.

And Light Is Noisy Too

Photon Shot Noise

There is something else that we now also need to consider with these very sensitive cameras - the noise that exists in light itself. It’s called photon shot noise and it occurs because most light emitters include small random fluctuations in the number of photons they produce. When you have large amounts of light, these small fluctuations are rarely seen as they make up only a small percentage of the overall light level. And when there is no light, then there are no fluctuations, so in absolute darkness there is no photon shot noise. But where we do tend to notice this noise the most is when shooting at low light levels. At these low light levels, the photon shot noise can be a visually significant part of the noise in an image. It’s why the image you see through a military style image intensifier is very “sparkly.” A lot of that noise is noise in the light itself being amplified by the intensifier.

A camera like the Sony FX3 or FX6, when shooting at 12,800 ISO, has a sufficiently low internal noise level that you are able to see the photon shot noise. This noise isn’t seen so much in the deepest shadows but more in the lower mid-range, perhaps between 20% to 40%, so perhaps over the darker parts of a face it is hard to tell whether what you are seeing is electronic shot noise or photon shot noise.

There isn’t really a lot you can do about it in the camera or in post production other than applying more electronic noise reduction. But adding a little more light into your scene can help lift faces, etc., up out of the most noisy areas.

So, while more sensitivity does allow you to shoot at lower light levels, it doesn’t mean that a good result is guaranteed, especially if you don’t have enough contrast.

Controlling, adding and sculpting the light in a scene remains just as important today as it has always been. Only now you may not need to add quite as much light as when 25 ASA film stocks were the norm.