09-08-2020 - Case Study

Breaking Down the Script - Part 3 - Composition and Light

By:

Photo at top of page, Vittorio Storaro, ASC with the Sony F65 on the set of "Cafe Society"

Filters

Filtration is a subtle thing, but still part of a cinematographer's creative arsenal. The cinematographer Chris Doyle is particularly interesting in this regard. Daylight and interior light have different color characteristics, as do light sources like fluorescent tubes, candles, streetlights and every other type of light. They are all measured and delineated by units of degrees Kelvin measuring color temperature. The human eye adapts very quickly to dominant colors, so we don't clearly see the difference in color temperatures, but the camera does. When two sources, say exterior daylight, and interior illumination, don't match, it looks surreal, so cinematographers use filters on either the camera or the lights (or windows) to make them match. But Doyle was revolutionary in his approach and would not use correction filters. Instead he would mix many different light sources of several different color temperatures, even harsh lights with strong color casts, like phosphor vapor lights. Horrible the first time you see it. Then you recognize it's genius. He almost single-handedly changed the attitude of many cinematographers towards uncorrected light sources. Again, a creative choice that didn't come from the screenplay and was probably determined during the script breakdown. These are the sorts of creative choices I am advocating. There are many other examples of filmmakers and cinematographers making radical creative choices. The director Gaspar Noé creates stunning and imaginative images; you will never forget seeing a film of his.

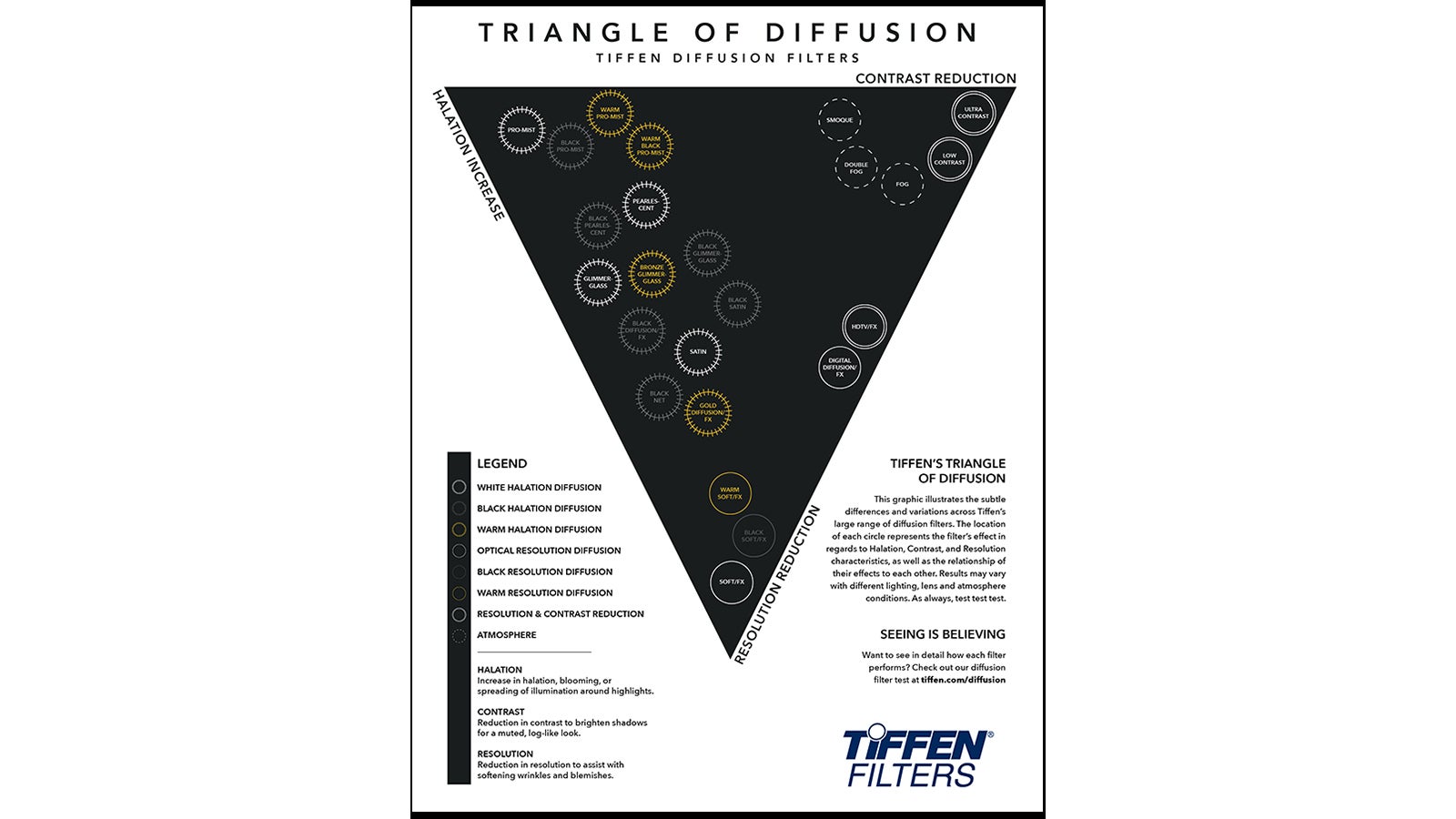

Other filters can be more subtle in their treatment of the image. Diffusion filters can soften the appearance of actors. Other filters can cause highlights to glow, or halate. I used to use a silk stocking material on the back of lenses to solarize areas of high exposure and reduce the black density of shadows while slightly softening the mid-range. Again, I am not advocating any individual creative choice, but just emphasizing the need to make creative choices. Again, nothing should be arbitrary as every lens, filter, camera movement and compositional choice will influence the audience.

Triangle of Diffusion for Tiffen diffusion filters

Composition

Many decisions about composition are made on set during the blocking with the actors and the director. But as the composition within the frame profoundly influences the audience's perception of action and character, it bears thinking about during the script breakdown.

It is impossible to list all the many and varied ways that one can use composition. But it's worth considering a few broad principles.

The canon of Western art has established certain orthodoxies around the concepts of composition. Two fundamental tenets are the "Rule of Thirds" and the "Golden Mean". I find the "Rule of Thirds" more useful.

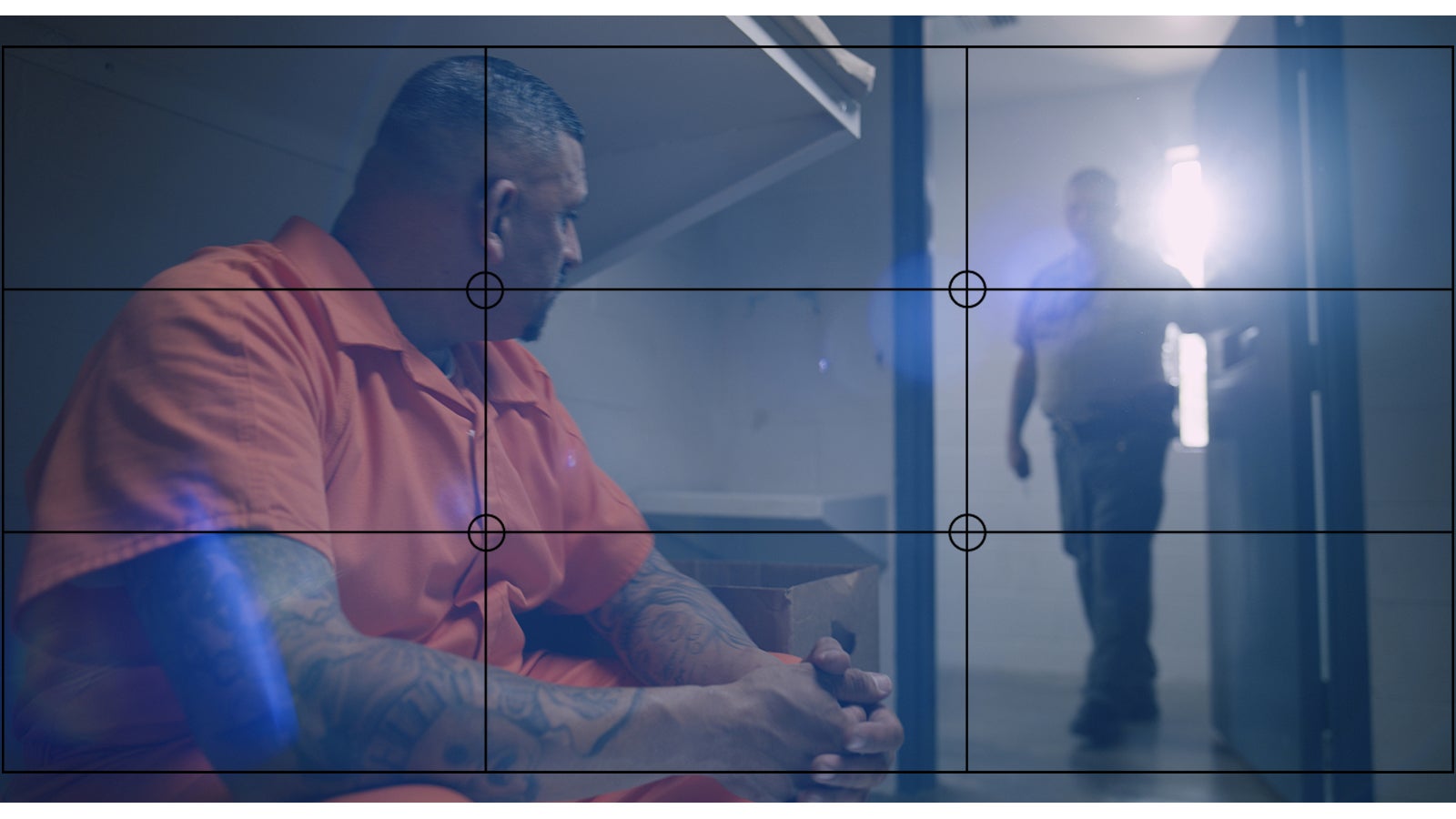

It has been determined that viewers find a one-third to two-thirds balance pleasing. Why this is so is a mystery, but it has been proven often enough that we can accept it a priori. In practice, in the motion picture frame, a principal subject is ideally framed one-third of the way from the side of the frame and two-thirds from the other side of the frame. In a close-up, the subject's eyes are typically one third from the top of a frame and two thirds from the bottom. This isn't to say that every composition has to be this way. In fact, some of the most interesting compositions created by cinematographers violate this rule. This is interesting, and I think it is because when the audience grows used to one thing, in fact, when they anticipate one thing, the greatest impact comes when you don't provide what they anticipate. Consider this example: an asymmetrical composition with the subject at the very edge of the frame looking towards the edge of the frame. Normally they would be looking towards the empty space, into frame, which would create a sense of balance. What is the result of this alternative composition? Fascinatingly, this composition has been shown to create tension in an audience; it puts them on edge. It makes them nervous. That may go to the director's intention for the scene and is therefore a potential tool for the cinematographer.

Frame from "R&R," by Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, shot on VENICE with Zeiss Supreme Prime Radiance lenses

Another device a cinematographer might use is to not show a character's face. This may seem a strange choice, but it is very effective. When the camera is pointing at the back of a subject's head, for example, the audience is denied clues as to what the subject is feeling and thinking, creating a sense of mystery and again, tension. The back of the head is also a place of vulnerability, so it can make the character seem vulnerable.

There are hundreds of other compositional devices available to the cinematographer, and in the script breakdown, as each sequence is examined, the cinematographer will think about how composition can be used to serve the director's intentions. Asymmetry? Shoot from Behind? Perhaps frame a subject within a natural frame on a set, (like a doorframe), to make them seem trapped or to represent the idea of limit (look at the last frame of John Ford's masterpiece "The Searchers", or the shutting door at the end of Coppola's "The Godfather". All are choices. Composition is a language that can be used to convey ideas subtly to an audience.

Bernstein directing Rhys Ifans and Romola Garai on the set of "Dominion," directional light through the window

Lighting

Lighting is a language, indeed one of the principal languages used by the cinematographer. During the script-breakdown, I find it useful to consider different categories of lighting; the quality of the light, lighting color, lighting texture and movement, and highlights and shadows.

The quality of the light

Lighting plans on bigger films are often complex and require the cinematographer to first see the location. But before the scout, the cinematographer can consider some philosophic approaches to lighting which will inform their subsequent work, particularly considerations pertaining to the quality of the light.

As I look at individual scenes during the script-breakdown, the first thing I think about is the general quality of the light I will be using, specifically, should the light be directional or soft (non-directional)?

Directional light is more dramatic and creates more and harsher shadows. It highlights textures, so it can be harder on faces as it shows blemishes. It also creates more scene contrast and arguably, more emotion.

Soft light is a seemingly directionless light that provides a general illumination but little modeling. It creates a flatter image, and it mutes colors. It's also very forgiving. Soft lighting rarely looks terrible. Subjects don't move in and out of unattractive shadows because there aren't any.

Overall exposure is really the least interesting thing about cinematography for the cinematographer. A good cinematographer is more interested in what effect lighting will have on the audience's perception of character and action. With this in mind, they may choose hard directional light for dramatic intention. Or they might choose soft light to underplay drama, or for comedy, or to replicate the light in a location; the flat fluorescent overhead lighting in an office for example. The apparent source of light on a set is called the motivating light source.

There is a point of contention around the concept of motivating light sources. Some cinematographers feel creative intention and creative intention only should determine lighting direction and quality. They don't care about motivating sources (within reason), and they don't care where the light should be coming from based on existing lighting sources (like lamps in a room on a set); rather, they want to use light to create an emotional reaction in the audience. I agree, but others may not. To me, letting an existing light source shape your creative decisions is an arbitrary decision-making process. The accident of a light source's position is not going to speak to your audience about bigger ideas. I have spent thirty years putting lights where I thought they would be interesting and evocative rather than based on the physics of their actual position. Not once in all those years has anyone said the lighting isn't consistent with the visible sources. That's not what audiences look at; in fact, they aren't concerned about physics. They are interested in the story, in emotion, and in character. Not physics.

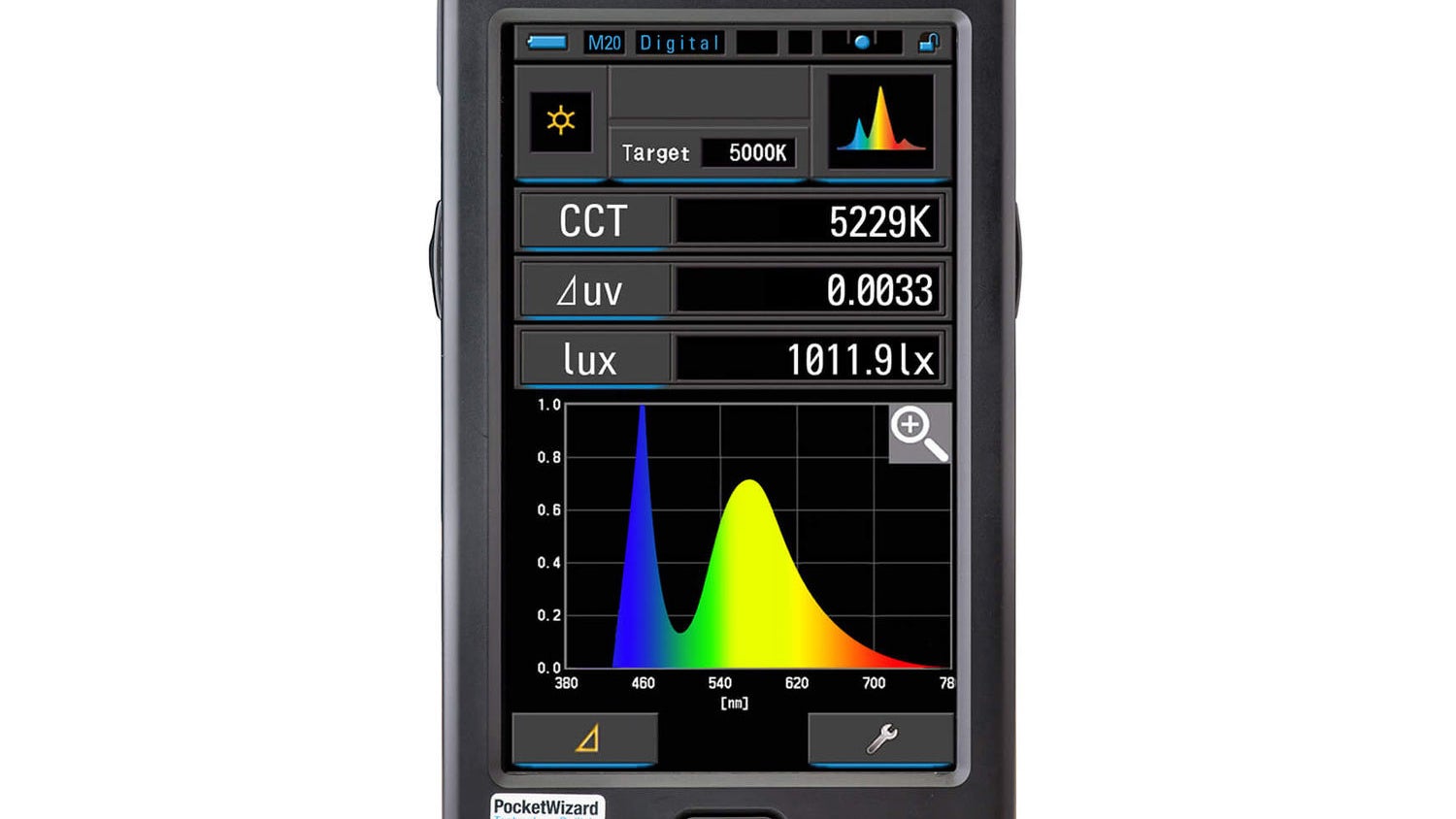

Screen from color meter

Lighting color

I mentioned earlier the remarkable work of Chris Doyle and his bold decisions to leave lights uncorrected and to mix sources. When his work first began to appear on world screens, some cinematographers thought that it was technically unsound, which in some respects it is. Most of us were taught that lighting should be seamless and invisible. Chris Doyle did the opposite. What was interesting was the audience's reaction to his work. They didn't question whether his lighting was right or wrong. Instead, they were simply affected by it; they found it disturbing, dreamlike, and sometimes nightmarish. This is exactly the effect that Doyle and the director, Wong Kar-wai were aiming for, and it goes to what I am talking about here. They used lighting to create a feeling in the audience. That is what they considered the purpose of lighting to be, and they used color to achieve it. Even if a cinematographer doesn't go as far as Chris Doyle, every cinematographer needs to consider the things Doyle did and still does; how to use the color of light as a language in their own films. I certainly do. Sometimes I will bathe my subjects in the orange of a street light. Sometimes a golden wash at sunset, or perhaps a deep blue when it seems right. Color is a creative tool.

Lighting texture and movement

Lighting isn't just about illumination. Lighting shapes and changes that which it illuminates.

A directional light through a window can seem wholly natural and be attractive on a subject. But when you hang sheer curtains with a subtle pattern on the window, the light becomes interesting and not just attractive. The created lighting texture plays across the face and body of the subject, emphasizing the slightest movements and allowing things like the eyes and mouth to come in and out of shadow. The audience will feel things more powerfully than if the light was just flat and non-directional.

Sometimes I use a "cucoloris" to create patterns, though sometimes I simplify the technique and take a metal frame and put tape across it to create the exact shapes I want. This is where lighting can become fascinating and where people begin to realize it isn't just about illumination. It's about using the language of light to create feelings in an audience.

Moving lights are also fascinating. One of the more common uses of moving light is to create the illusion of police lights on a set. The cinematographer will mount a spinning blue light on a stand and put it near the subject. To the audience, it's a nearby police car. Of course it isn't but, it's easier than bringing a police car onto set.

I also like to have grips hold branches in front of lights and shake them to create moving patterns. It's like trees moving in a wind storm. Very evocative.

Like the other areas I have touched on in this article, there are too many techniques to list here. But discussing all the techniques isn't my intention here. Rather, it is to list the different things a cinematographer should consider when creating their visual script during the script breakdown.

Frame of Brando in "Apocalypse Now" lensed by DP Vittorio Storaro, ASC

Highlights and shadows

Sometimes the most interesting part of a frame is the part that is not lit. A good example is Marlon Brando at the end of "Apocalypse Now." Look at what cinematographer Vittorio Storaro choose to do. In his breakdown, he considered the desire of the director that the Brando character was to represent an idea not a man. The film originated from the novella "Heart of Darkness" by Joseph Conrad, and much of Conrad is about the duality of the human spirit, the light and dark, and the good and evil in each of us. Conrad's characters are emblematic of the different impulses in our darkest recesses. So the character Kurtz, as played by Brando, represents the dark part of our nature. Storaro, the film's cinematographer, made a couple of decisions. To make Brando the "heart of darkness," he actually left him mostly in shadow in the key scenes at the film's denouement. But he also wanted the character to embody amorphous spiritual concepts, so he wanted to take away his physicality, and he did so by only providing simple backlight and a little foreground exposure. In the end, Brando became a voice, a brief illumination of an eye, but most of all, something surreal and hypnotic. This is what brilliant lighting can do. This is what thinking about and making use of all the languages available to the cinematographer is about; the breaking down of a script by a cinematographer is not really breaking something down. Rather it is about the creation of a visual script that moves an audience effectively and powerfully with images. This is the art of cinematography.

Follow this link for Part 1 of this article: Breaking Down the Script - Part 1 - Locations

Follow this link for Part 1 of this article: Breaking Down the Script - Part 2 - The Creative Breakdown

About the author:

Steven Bernstein, DGA, ASC, WGA is an ASC outstanding achievement nominee for the TV series Magic City. He shot the Oscar winning film “Monster,” “Kicking and Screaming,” directed by Noah Baumbach, “White Chicks” and some 50 other features and television shows. The second film he wrote and directed, “Last Call,” stars John Malkovich, Rhys Ifans, Rodrigo Santoro, Zosia Mamet, Tony Hale, Romola Garai and Phil Ettinger, is scheduled for release later this year.

Steven can be followed at Stevenbernsteindirectorwriter on instagram where he regularly posts short insights and illustrations about filmmaking.