03-21-2022 - Case Study

Getting Hired: How Does a Director Choose a DP?

By:

First, they have to meet them. It is a big industry spread around the world, and there are always more cinematographers available for projects than there are projects. In fact, there is a substantial amount of competition at every level of production. So, the first issue is how does the cinematographer get on the director's radar?

Agents. Like with actors, most cinematographers need to have agents. Directors are much in demand as they go into production. Whatever their good intentions, as their time becomes more limited, they want an efficient method of quickly shortlisting key creative department heads. To this end, they will have a member of their production staff reach out to major agencies and ask them to send showreels and resumes to the production office to be given to the director.

I have been that director. Even though I know many cinematographers socially and from the American Society of Cinematographers, I still thumb through resumes at the beginning of pre-production for my films. Most directors will look for the same things on a DP’s resume: films they know and admire, crew and personnel familiar to the director so they can ask for references, and the type of films that would suggest a cinematographer has a specialized skill set that is applicable to the project.

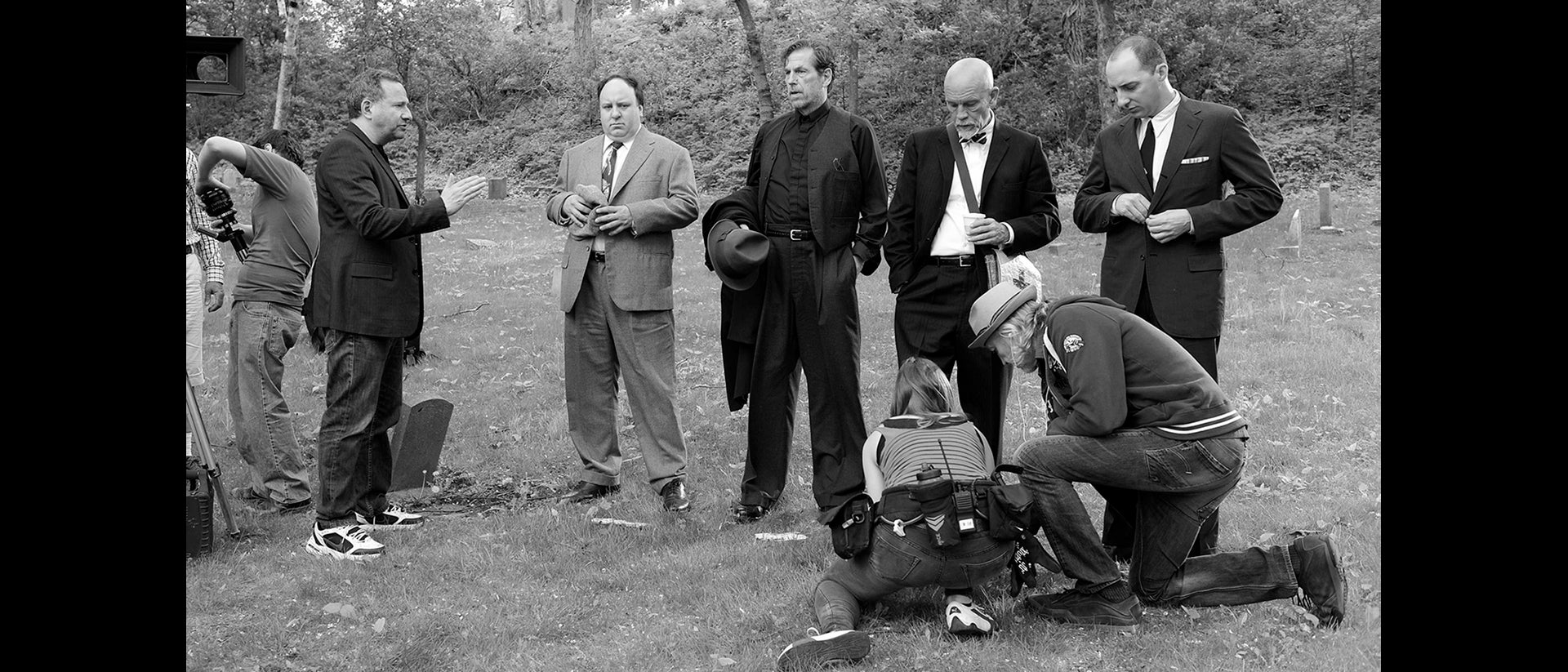

The author directing John Malkovich on the set of "Last Call"

A great many resumes land on the desks of directors who are looking for cinematographers. Sometimes producers or production managers will run interference and filter out individuals who might have more limited experience or experience not specific to what the director will need and want, like commercials or individuals with bad reputations.

The agents themselves might also act as filters if, on hearing the brief for the film being produced, recognize that certain clients don't have the capabilities or experience that the director is likely to want. This can be upsetting to the excluded cinematographer, who wants to be presented so they might get their big break. But agencies are conscious of their own reputations. If they try to force their clients onto directors who don't consider them of a sufficient level, it will hurt the reputation of the agency and the ability of the agent to sell clients from that agency in the future.

This goes to another issue for cinematographers: whether it's better to have representation at a large or small agency. The larger agencies might also represent directors, producers, and actors and have their finger on projects as they develop. They may be able to package a cinematographer as part of more extensive hiring for a particular project. They may also be able to get a cinematographer to meet a director before a project is announced. A larger agency will also have more prestige, and their clients are more likely to get consideration.

A smaller agency trying to build a reputation is generally more inclined to push its clients. This sounds like an advantage, and sometimes it is, but they also have a harder time reaching directors on larger films.

Some cinematographers don't use agencies and have their lawyer or other representative negotiate their deals. This is perfectly reasonable if the cinematographer has enough existing clients or has a substantive enough reputation that they don't need someone specifically marketing them.

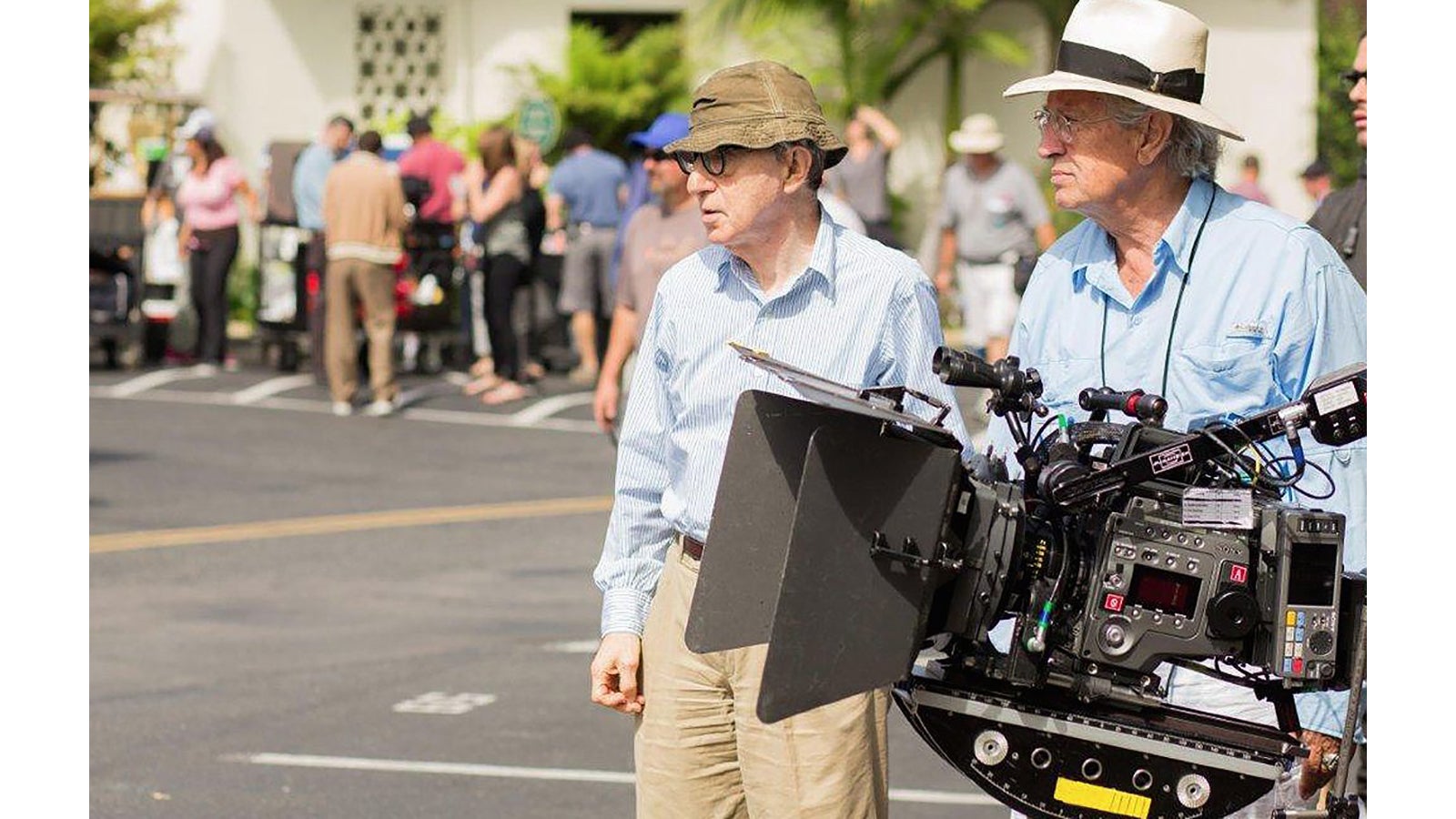

Woody Allen and Vittorio Storaro

Reputation is significant, and because cinematographers are not kept on staff at studios or most production companies, at least to produce feature films and major episodic television, a freelance cinematographer's reputation will be another major factor in their hiring. Having a recently released film or an episode on television with a run of success is an excellent advantage for a cinematographer looking for work. Most people are suspicious of people selling to them, including agents selling their clients. It is recognized that the relationship is transactional. But when a film has wide success, good reviews, and possibly some award nominations, a director will take it as an affirmation of quality, perhaps even an opportunity to have that quality added to their own production. Directors will actively seek cinematographers who have shot films that they admire or admire the cinematography in the film, if not the film itself. This is why it is sometimes a good idea for cinematographers at the beginning of their careers to do projects that may be smaller but have great visual potential. Oddly, even films without great visual quality that are successful in the marketplace usually help the career of the cinematographer who shot them. So, the principle here is, work generates work.

The reputation of a cinematographer is not wholly dependent on the success of the projects they work on. Directors worry about many things, as do their producers with whom they collaborate. One of the things on which a director will focus is the personality of a cinematographer. A sullen artist inclined to fits of temper, late arrivals, or willful resistance to support a previous director's vision will probably preclude another director wanting to work with them. It isn't just about technical ability; film sets are surprisingly claustrophobic. Everyone has to work very closely with each other under considerable pressure and sometimes less than ideal circumstances. An easy-going, respectful, and collaborative personality is usually preferred to someone of perhaps greater skill but aberrant behavior.

The author directing Rodrigo Santoro on the set of "Last Call"

A cinematographer's reputation in terms of their character and leadership is so important in their potential to be hired, that if they are involved in a dispute on set, it is advisable that they quickly resolve it with an apology, good explanation, and try never to repeat the egregious action. Individuals with the considerable drive necessary to become department heads also have strong egos or ego attachments to their own ideas. A DP must develop the maturity to recognize that being right is sometimes less important than being amenable and co-operative. There's an oft-used expression in describing people who were difficult to work with on film sets, "Life is too short to work with them again." Yes, directors and professionals want to make great films. Still, they don't want to work in a toxic or overly competitive environment.

If a cinematographer is unfortunate enough to develop a bad reputation, it's wise to remember that it's better to admit than deny, which seems paradoxical. However, individuals who say, "I made mistakes in the past, this is what I learned from them, and this is what I do now" are more likely to be believed than individuals who admit to nothing. This may seem an excessive number of paragraphs to address reputation instead of the technical aspects of cinematography, or the precise reasons a director hires a cinematographer, but that's the point. After themselves and the actors, a director understands that the cinematographer may be the most important person on set. In fact, the cinematographer is on set more than the director or the actors, lighting and setting shots up when those other key creatives are in their trailers. So how a cinematographer works with others and the atmosphere they create will be essential to the film's success.

Director Joseph Kosinski with DPs Claudio Miranda and Erik Messerschmidt

DP Reels

If the agency submission, or the compelling film that was recently released, has captured the attention of the director, they will want to look at the cinematographer's reel. I talked in an earlier article about what a reel should have. Still, it bears reviewing—making an individual shot beautiful can be a challenge but isn't the real measure of a cinematographer's ability. An entire sequence that is beautiful or engaging is better evidence of a high skill level and should be included on any reel. Many young cinematographers think quantity is of value, so they will include shots and sequences from virtually everything they've done, including things of a relatively low value or poor quality, like bad acting and cheat sets. It's tough for the director or viewer to separate their visceral response to poor general quality from a specific analysis of the virtues of the cinematography. So less is more; a reel can be short but must only feature the highest quality material. Directors are also looking for specific skill sets relevant to the film they are about to make. It can be argued that a skilled cinematographer can take principles and apply them to shots or sequences they haven't done before. But film and television sets are high-risk working environments. A person can fail, not only for not doing their job well but having hired someone else who can't do their job. So, directors are often reluctant to take risks on unproven commodities, like DPs, who haven't shot a film like theirs before. DPs might also come from commercials or videos or documentaries and have considerable abilities but still be viewed as a risk by many directors. If you want to shoot features, you have to work on features as early and frequently as possible, even if it's as a camera operator, even better as a second unit cinematographer. Maybe your work will have to be on low-budget films to begin with, and then slowly climb the ladder. But even directors who are radical in their own vision tend to be conservative in their hiring practices regarding cinematographers.

Conversely, directors are natural leaders and are interested in skills and experiences that they don't have and complement their own qualities. So, although a cinematographer should fill their reel with feature material (if they have it available), they should supplement it with unique or original approaches they may bring to their craft as a cinematographer. For example, a DP adept at preparing material for visual effects, using the new volume LED screens, or a DP who has done interesting experimentation with altering shutter angles during action sequences will interest a director who wants to learn how they're done and potentially can be applied to their own film. So, it's reasonable to say a director wants to see a combination of experience with new and possibly radical cutting-edge ideas.

The author framing up a shot on "Last Call"

The Interview

Demonstrating creative impetus is a significant part of getting hired by a director. The reel may have just enough to get the cinematographer to the important next stage: the interview. But a cinematographer shouldn't rely wholly on their reel and simply show up at the first face-to-face. Again, it's a good general rule for cinematographers to not only do what is required but go beyond any specific requirement. I always showed up with books, photos, examples of paintings, videos, and color swatches for the director, to illustrate some of the creative ideas that I had evolved on reading the script. When I am directing, I am similarly impressed by people who show up prepared. It doesn't mean that the creative vision presented by the cinematographer is going to be correct for the film. Still, it stimulates a response from the director and shows a creative engagement on the part of the cinematographer that directors covet.

The interview will inevitably lead to two other areas: the cinematographer's working technique and the crew they work with. In discussing the cinematographer's work technique, the director will want to know primarily how the director and the cinematographer will communicate. The director will understand that they provide the overall vision. Still, inevitably, there is some divergence in understanding how to achieve that vision with any collaboration. An experienced or inexperienced director will want to know that the cinematographer will present their notions in a respectful, organized, and preferably private method. A DP rolling their eyes behind the back of a director can instantly undermine the director with the crew. The DP is the crew’s leader; if they treat the director with disdain the crew will soon follow, and all is lost. Statements of fidelity and loyalty at an initial meeting can go a long way toward reassuring a director's concerns in this regard.

In film and particularly in television, time is critical as it directly correlates to the expenditure of money. Because rigging lights, laying track, running cables, and placing cameras are all time-consuming, the cinematographer is one of the main determinants of whether a project moves along quickly or slowly, finishes on time and economically, or runs into overtime and additional expense. A cinematographer who directly addresses the issue of their working speed, while hopefully making clear that they won't be making important creative compromises as a sacrifice to speed, will be more likely to get the job. Like cinematographers with aberrant personalities, slow cinematographers generally aren't desired collaborators. Although it should be said, on larger projects where all the departments will be taking considerably more time, a cinematographer who is a great artist with a proven track record is more likely to be given the time to create spectacular shots. But this privilege is reserved for a select few and not recommended for someone at the beginning of their career.

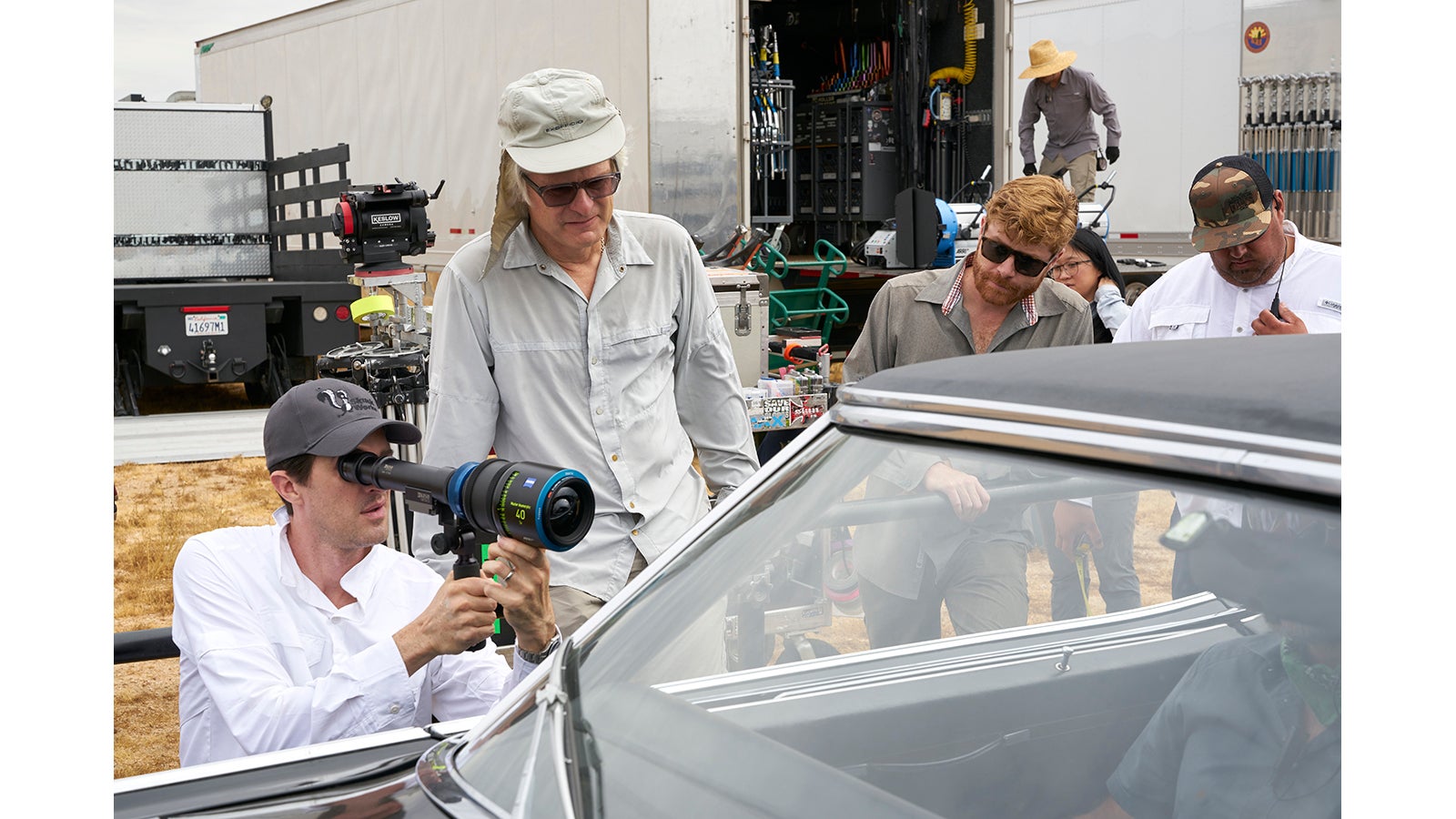

Behind the scenes of "Kate" for Netflix

The director will also want to know about the team the cinematographer brings with them. The bigger the film project, the more important specialization becomes, although, on independent films, there is an inclination for cinematographers to multitask. Multitasking is possible but dangerous as when you have a single job, even if that job is supervising others, you are less inclined to make an error due to a lack of concentration. If you're thinking about camera operating at an individual moment, you may not be thinking about how a shot isn't quite working. As films get bigger and you have multiple camera operators and hundreds of lights, the people manning their equipment will determine the quality of the actual work and the time it takes to achieve it. So, a cinematographer who comes to a meeting with the names of top crew members with vast experience who are willing to act as collaborators, and have collaborated with the cinematographer, is a potent elixir with which to convince a director to hire them.

Many cinematographers own some of their equipment. Many own their camera. I am often asked if this is a good way to attract work. I don't believe it is. What will ultimately determine the quality of the image and success of the working day is the creative imagination, experience, and success in the application that the cinematographer will bring. None of that comes from the camera; it comes from the person. It's like a band hiring a drummer not because he plays exceptionally well but because he has a set of drums. But there is something else to consider. A cinematographer also acts as a consultant to the production and the director. The choice of which camera to use, which size sensor would be appropriate, what lenses and filtration to use, what lights to use, what tripod and dolly to use, all must be determined not by which items create the greatest profitability for the cinematographer, but which items best serve the vision of the director and help make the best film. If the cinematographer has a large kit and it isn't appropriate for the film they are working on, there is an obvious and profound conflict of interest.

Director Alan Ball and DP Khalid Mohtaseb on the set of Amazon's "Uncle Frank"

Of course, many highly skilled cinematographers own a great deal of equipment. Then you could have the ideal combination of creative skills and equipment, potentially offered at a discount to the production. Even in the absence of a discount, it might be specially modified and well maintained and could be of service to the production. But the skills should come before the purchase of the gear. Indeed, many directors working on independent films will be hoping for a cinematographer offering equipment on the cheap. Still, if the cinematographer can't deliver as a leader, collaborator, artist, and technician, the discount won't matter much to the director or anyone else.

Another big question that a director will have for the cinematographer is their specific experience with actors. Acting is a hard job, particularly in film and television, as there is no audience present. Films are generally shot out of order, there are lights, cameras, equipment, and many distractions, and it takes a great deal of skill and concentration for the actor to deliver what they're paid to deliver. Actors want to know where the camera is and the size of the individual shot. They may want to know that they are well lit. They will want to know they can rely on the cinematographer, who can profoundly affect their appearance in the audience's experience. A cinematographer who has never been around prominent actors or who is dealing with major actors for the first time may be nervous or cause the actors to be nervous. Cinematographers are meant to provide leadership and a calming influence, so directors will want to know about a cinematographer's specific experience with performers. This is why I suggest that cinematographers include sequences with known actors with whom they have worked in the past on their show reels.

Pedro Almodovar framing up a shot on "Parallel Mothers"

A cinematographer's demeanor at the meeting with the director is also consequential. The temptation from an inexperienced person may be to attempt to sell themselves to the director, listing their attributes or possibly even overstating their qualities. The dilemma here goes to the cinematographer's peculiar position on a film, part technician, part assistant director, part above the line and below, and part artist. The director is often surrounded by producers, agents, and managers trying to sell something. A natural inclination in anyone being pressured, like directors, is to distrust the people doing the selling. So, the last thing a cinematographer should do when hoping to get a job with the director is to sell. It's far better to talk about artistic vision and how working quickly will better facilitate the director's realization of their vision. How the cinematographer's comfort with actors can help the actors provide a better performance that incorporates greater risk-taking and, therefore, a better understanding of the character. It's better that the cinematographer talks about the crew they bring with them and how the director's vision is more likely to be realized by using experienced specialists. This may seem like selling, and indirectly it is. Still, the focus is very much on the artistry and the shared creative visions of the key collaborators. Talking about art is more likely to get a cinematographer a job over the cinematographer simply explaining how virtuous and brilliant they are.