12-28-2020 - Technology

HDR: What is it, and why do we want to shoot for it? A Conversation with Bill Baggelaar of Sony Pictures - Part 2

By: Jeff Berlin

SonyCine.com recently sat down with Bill Baggelaar to discuss all things HDR.

Bill Baggelaar is Executive Vice President and Chief Technology Officer at Sony Pictures Entertainment, as well as the Executive Vice President and General Manager of Sony Innovation Studios.

As CTO, Bill brings his extensive experience in production, visual effects and post-production along with his work collaborating with industry partners and internally across Sony in developing and implementing key technologies that have been instrumental, including IMF, 4K and HDR. He is responsible for the technology strategy, direction and research & development efforts into emerging technologies that will shape the future of the studio and the industry.

Prior to joining Sony Pictures in 2011, he was Vice President of Technology at Warner Bros. Studios where he worked with the studio and the creative community to bring new technologies to feature animation, TV and film production.

Bill is a member of The Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences, The Television Academy and is a member of SMPTE.

Part 1 of this series can be found here: https://sonycine.com/articles/hdr--what-is-it-and-why-do-we-want-to-shoot-for-it--a-conversation-with-bill-baggelaar-of-sony-pictures/

Split image, HDR vs. SDR on a BVM-X300 set to SDR. Image shot on VENICE by Jeff Berlin

Jeff:

When you look at HDR on an SDR display why is the image so flat?

Bill:

Well, first off, you need to look at an HDR signal on a proper HDR display for it to look correct. But if you do look at an HDR PQ, or SMPTE ST-2084 signal on an SDR display essentially what you see is a logarithmic signal. It looks very flat and washed out. And that's because it is not intended to be viewed on a Rec709 or gamma 2.4 display. You need a proper HDR display to see the image correctly. This logarithmic signal is actually a concept more from the film world. When we started scanning film to make a digital version of it, we were always working in a logarithmic space.

So, Cineon, or DPX files for cinema, were always in what was called Cineon log. And Cineon log put a log curve on it. It always looked flat if you are looking at it on a TV or other Rec709 display or even on a computer display. It always looked very flat and washed out because you needed to actually invert the gamma in order to give it a correct contrast for the display output, whether it was a projector or a computer display or a TV.

So that concept is long held that we're able to carry more information in a log signal because we know that it has to go through an inversion process. We're able to carry more information in that signal with fewer bits of data. Or you could say in the same bits of data, we get more information back to be used in the color correction process down the line. So, it's a long-known concept in the film world of working in that log space.

Jeff:

What are the flavors of HDR that we're seeing now? And what do you think is going to come out on top?

Bill:

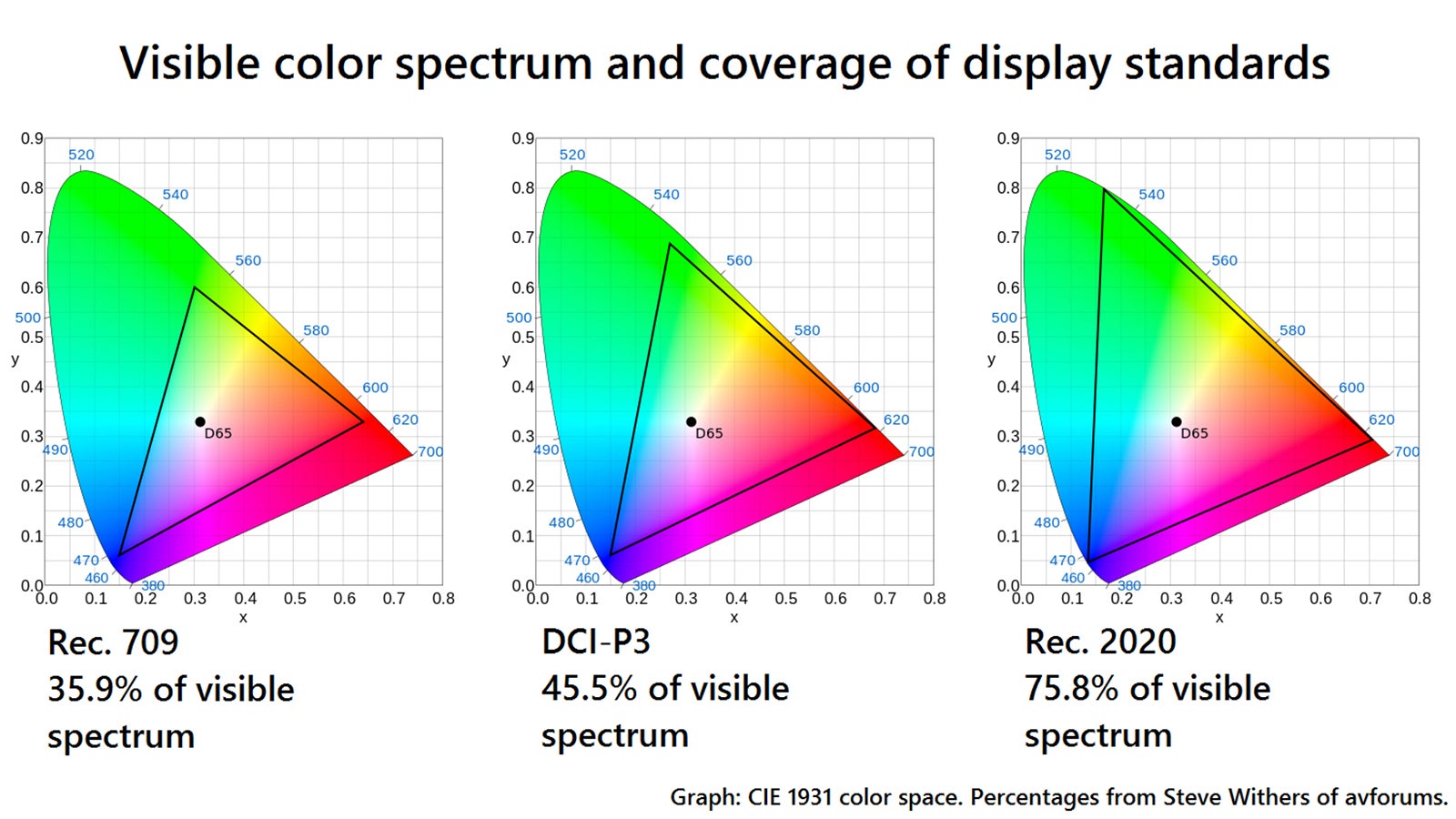

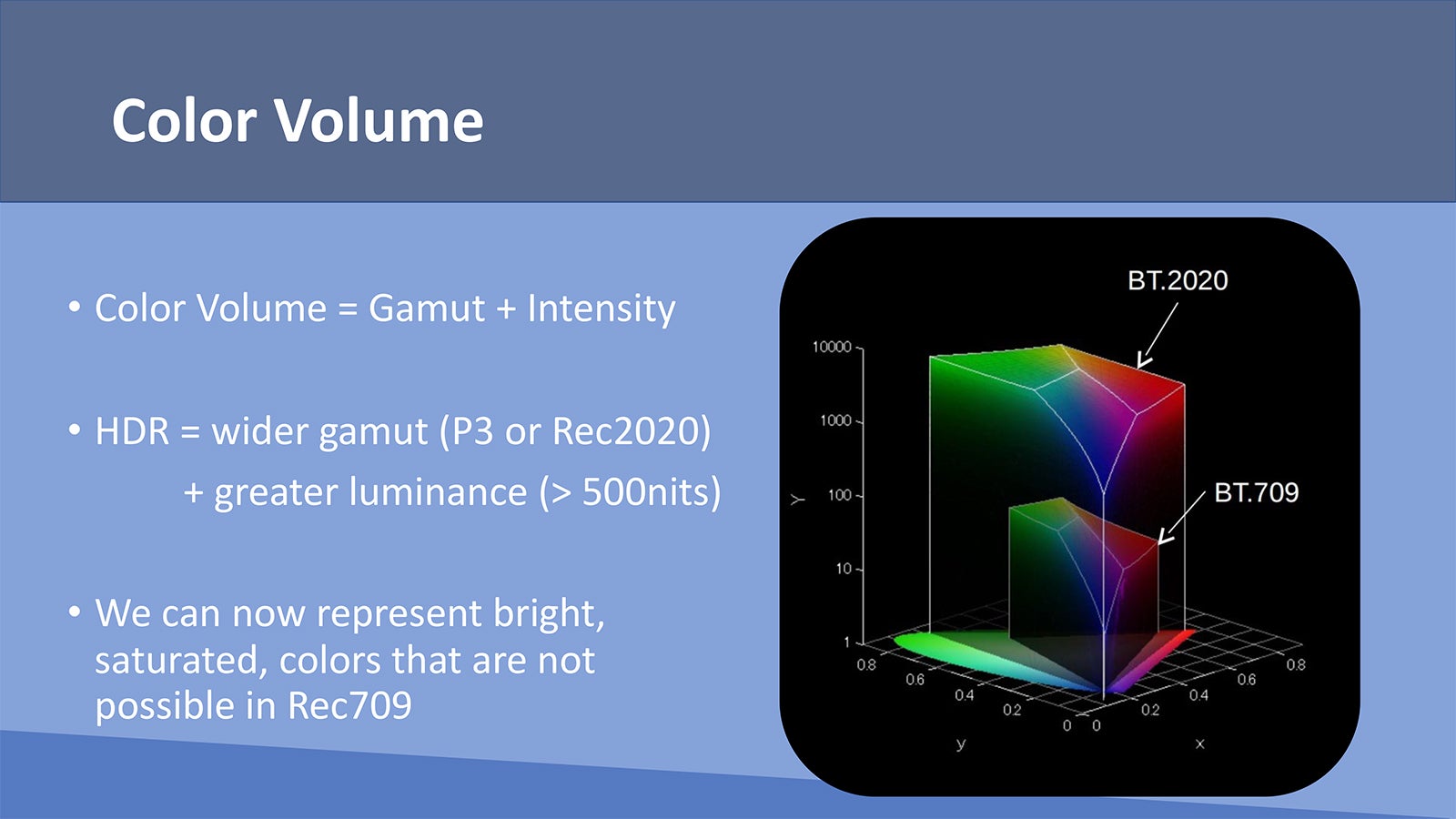

For mastering, we are actually saving our HDR masters with 12bits of color per channel in SMPTE ST-2084 or PQ format in a Rec2020 container. This was a conscious, forward-looking decision on the part of the studio to choose this format. All of Sony Pictures IMF (Interoperable Master Format) masters for theatrical and tv/episodic titles are mastered and saved in this format. For delivery to the home, there are a few different ways to get it there; HDR10, Dolby Vision, HDR10+ and HLG are the predominant home delivery flavors. HDR10 is a luminance descriptive output and is the baseline delivery for all of our HDR content, and then we use Dolby Vision to add dynamic metadata. We master practically all of our theatrical titles in HDR for home delivery, including our catalog and classic titles, and the majority of our HDR theatrical titles get Dolby Vision passes as well.

We use Dolby Vision to convert our HDR titles to SDR as well as tone map for HDR so we make sure that we're getting a very good, known representation in those displays that are Dolby Vision-capable.

There are other flavors of metadata out there too, like HDR10+, but we haven’t seen it gain much traction in the market just yet, I want our content to look great everywhere and I am a proponent of maintaining creative intent and for Sony Pictures, we feel that we can do that effectively with HDR10 and Dolby Vision today. If the market decides that there are other technologies that are impactful for maintaining that creative intent, we are ready to look at it and determine how we can add it into our masters.

HLG is another format for live broadcast delivery of HDR content. While we don’t master in HLG, our titles may be consumed in HLG on cable and satellite linear channels. We have worked with our licensees that use HLG to distribute HDR to ensure that a high-quality output is being maintained for our content. Live sports in HDR is typically being delivered in HLG. As a big NFL fan, I am happy to watch football, and really any sporting event, in any flavor of HDR. It’s a great experience.

Jeff:

For the TVs like Sony’s HDR OLEDs, like the A9F, when it snaps into Dolby Vision mode, what are the nits we are seeing?

Bill:

Well, it depends on the TV because all the TVs have different specifications. I think the newer OLEDs are anywhere from probably 500 to 600, possibly even 700 nits with really rich blacks. And then we have LED displays that are 1,000 even 1,500 nits. Some of the very large ones go up to 2,000 nits. The A1E is probably somewhere around 400-500nits. I still love watching HDR content, well, really any content, on my A1E.

It all really depends on the TV and the mode it's in, because even some of the modes will limit the highlights. So, if you're in Cinema Pro versus Standard on a Sony versus the custom modes, you will get different results. I would say the minimum capable display is probably around 600 nits, from Sony. There's a whole range of displays out there for people to choose from. All of the Sony displays really do a good job of maintaining the picture quality and provide a great viewing experience. We have worked closely with Sony Electronics for many years on the picture quality side of things with respect to UHD and HDR.

Jeff:

Let's talk about shooting for HDR. Of course, not everybody can afford to have a $40,000 BVM-X300 on set, so let’s discuss shooting for HDR without having HDR monitoring on set? What are your recommendations?

Bill:

We have produced a lot of HDR content. We've been doing this now for five years, six years? And the majority of those shows have not been monitoring HDR on set. So, we're able to produce very good results and I would say we have fantastic looking content that's in HDR. I don't think it is an absolute requirement. And if you hearken back to the film days, again just as an example, they were shooting in an HDR medium and they weren't even able to see what they were getting, until you had video taps and other things that gave you the ability to actually see what was coming through the lens. So there's already been an ability to capture higher dynamic range material without actually seeing it.

Given the modern ways of TV and film production, I think it's reasonable for people to want to know, "Okay, what does the scene look like in HDR?" Rather than shooting and assuming, you can now curate to an HDR output. There are many more HDR-capable displays available now including even small camera-mounted units. And I think people say, "Well, it doesn't do what the X300 or the HX310 can do. And while that may be true, I think you can get from them a very good representation of HDR at 400 nits. If you can get a small 400 nit display; Sony, for example, has a 17-inch HDR display, I think it's 400 nits, not quite sure, but that's a small enough display to represent what you need to know, which is what does my shadow detail look like? While you don't get all the highlight detail, you still get a good idea of what your HDR image looks like from shadows through the mid tones and into the highlights.

Now, you can monitor the signal as you normally would on a scope and other things to help you, so you don't have to have a $40,000 monitor on set to do it. I think that the bigger challenges with practical production issues relate more to having HDR dailies and editorial. Where you need more support to be able to make that work from an overall ecosystem within the production. You still need to support SDR viewing for all of the people who are looking on laptops and other non-HDR capable displays. But it's doable today, and it is getting more and more doable as the technologies and systems advance.

Jeff:

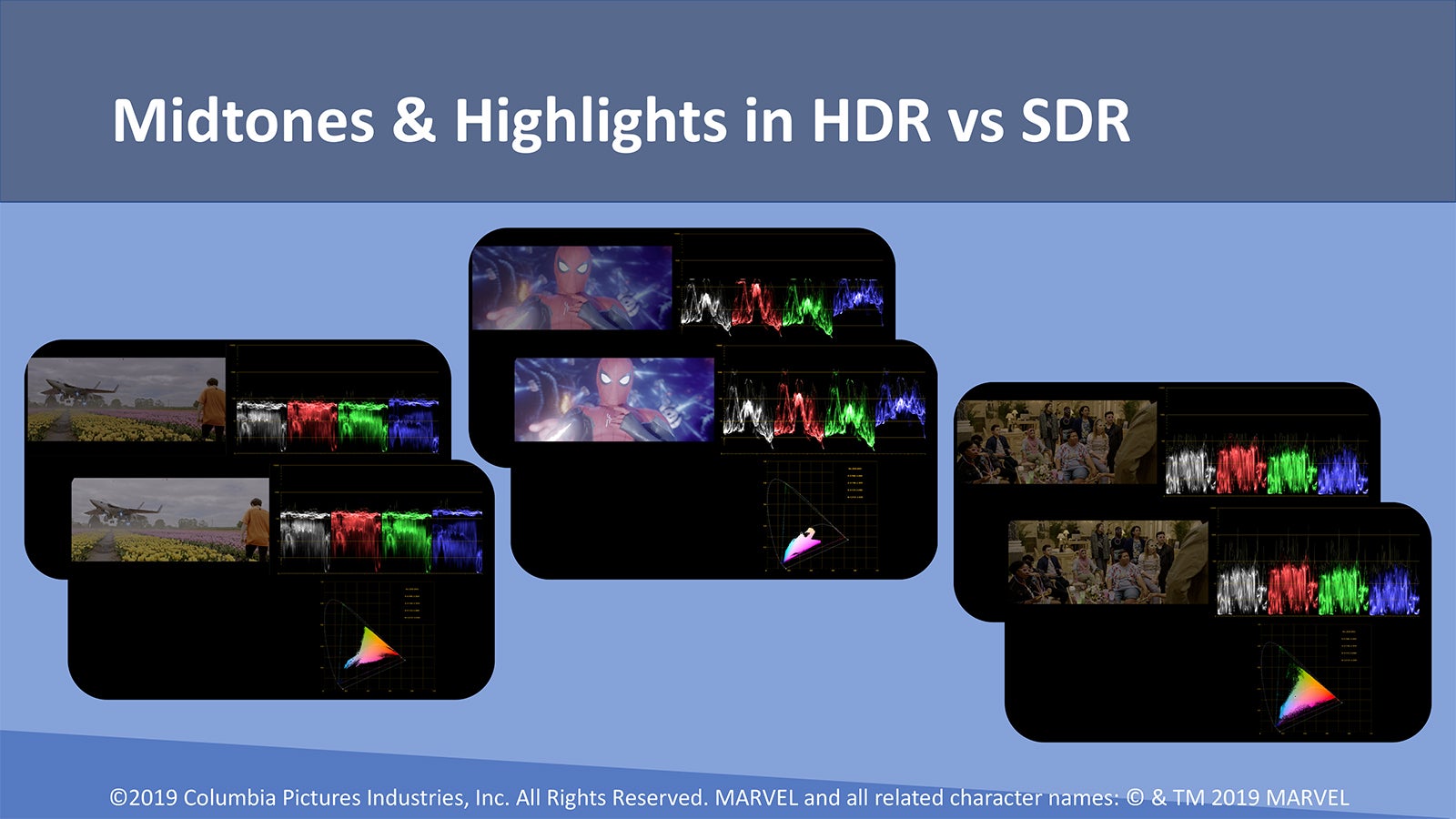

Would you say there are any rules of thumb that you think would be good for DPs, like using your waveform and scopes, protecting your shadows and highlights, things like that when you're not monitoring in HDR?

Bill:

Yes, I think that definitely almost all of the same rules apply. In the best scenario, you would probably be looking at a combo SDR and HDR image. You'd see what your HDR looks like and then have an SDR representation of that as well that will limit and roll off your highlights. That would be your best case. And that way, you can get a better feel for where you are, like, "Okay, I'm protecting for the shadows here but this is what it's going to potentially look like with my look on it in SDR as well," so that you make sure there's a good balance between the two, that you're not crushing it too much where the SDR signal is going to be affected.

And that could be by waveform as well. Making sure that you're not crushing your low end is really important in HDR. I think that's a bigger problem than the highlight issue, to be fair, because I think the cameras are very capable of capturing highlight detail but it's really easy to crush the bottom end a bit because, depending on the scopes, you don't always have as granular a view of the range in your shadows that you have in the highlights.

So, if you have an HDR scope, that would be the best case as well but certainly being mindful of trying to give yourself the latitude you need so that you can go into post while still maintaining your look. And certainly, exposure becomes really important, monitoring your exposure. A lot of times, I think a trap that DPs can fall into is that if with a calibrated monitor, they don't like the way it looks, somebody starts fiddling with the contrast or the black level on the monitor and you now are no longer looking at the signal as it’s being recorded, but rather with a “look” applied, which can lead to incorrect decisions or assumptions.

If you do that in the HDR world, you can end up underexposing and then you're having to lift up in post and in the HDR world with underexposed material, you really are adding noise that's very noticeable. And so, it's important to be mindful of getting a calibrated setup on set and sticking with that. And maybe doing some tests beforehand with the camera and an HDR monitor so that you know how the camera is going to react, and to get comfortable before they're in a live shooting scenario so they know how the entire system is working. Then they will know it'll be good downstream.

I think good shooting principles still apply with HDR. I always try to say even with digital cameras that they're not magic. HDR is not magic, although it can feel that way sometimes. It's really adhering to good shooting principles and making sure you understand how to use the tools appropriately for that shooting environment.

Jeff:

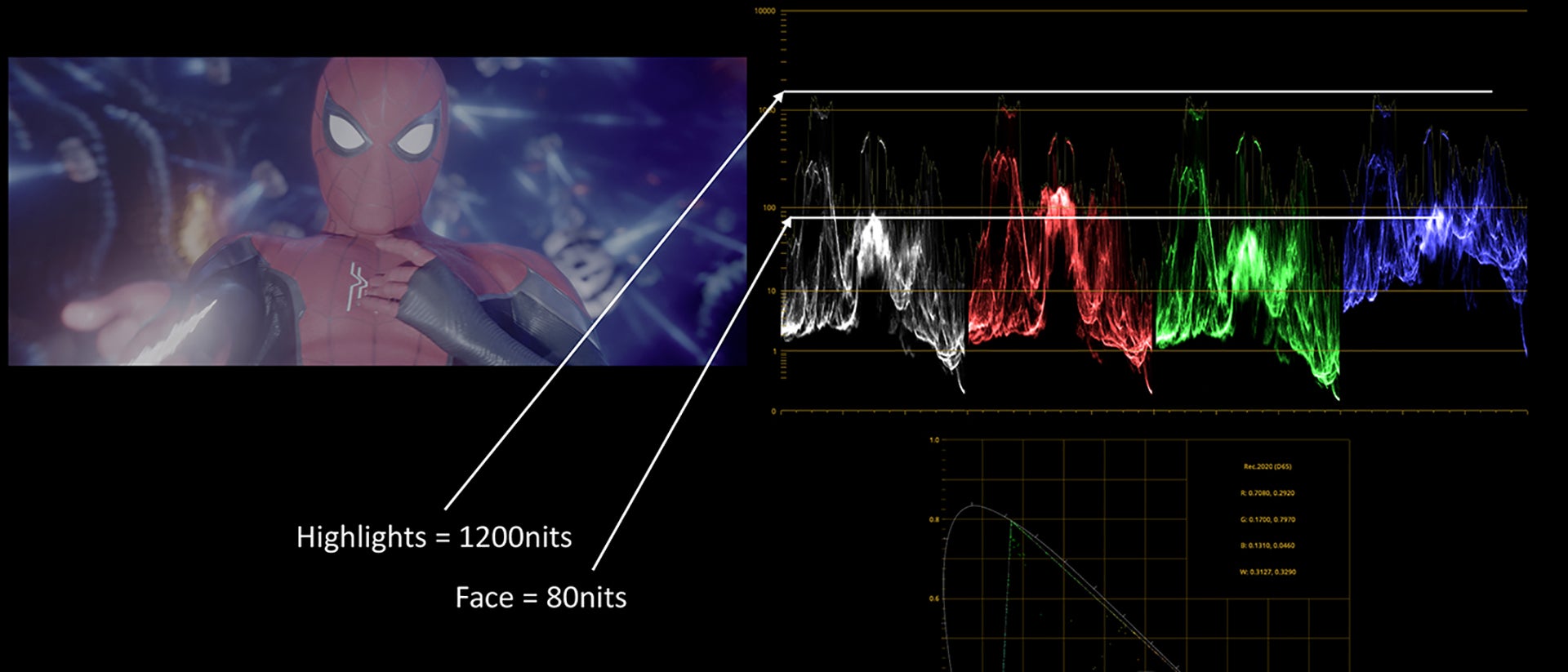

How about skin tones?

Bill:

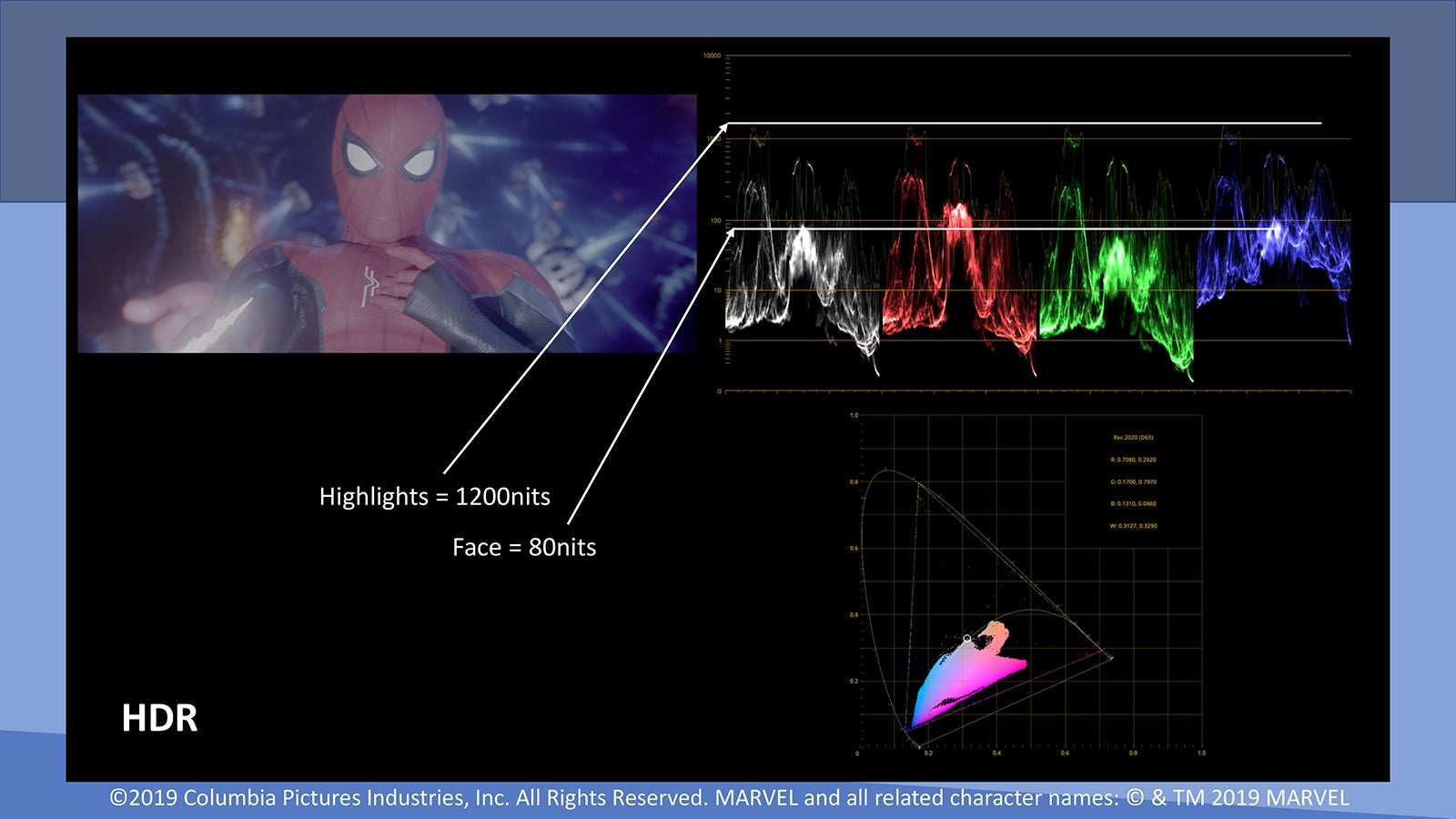

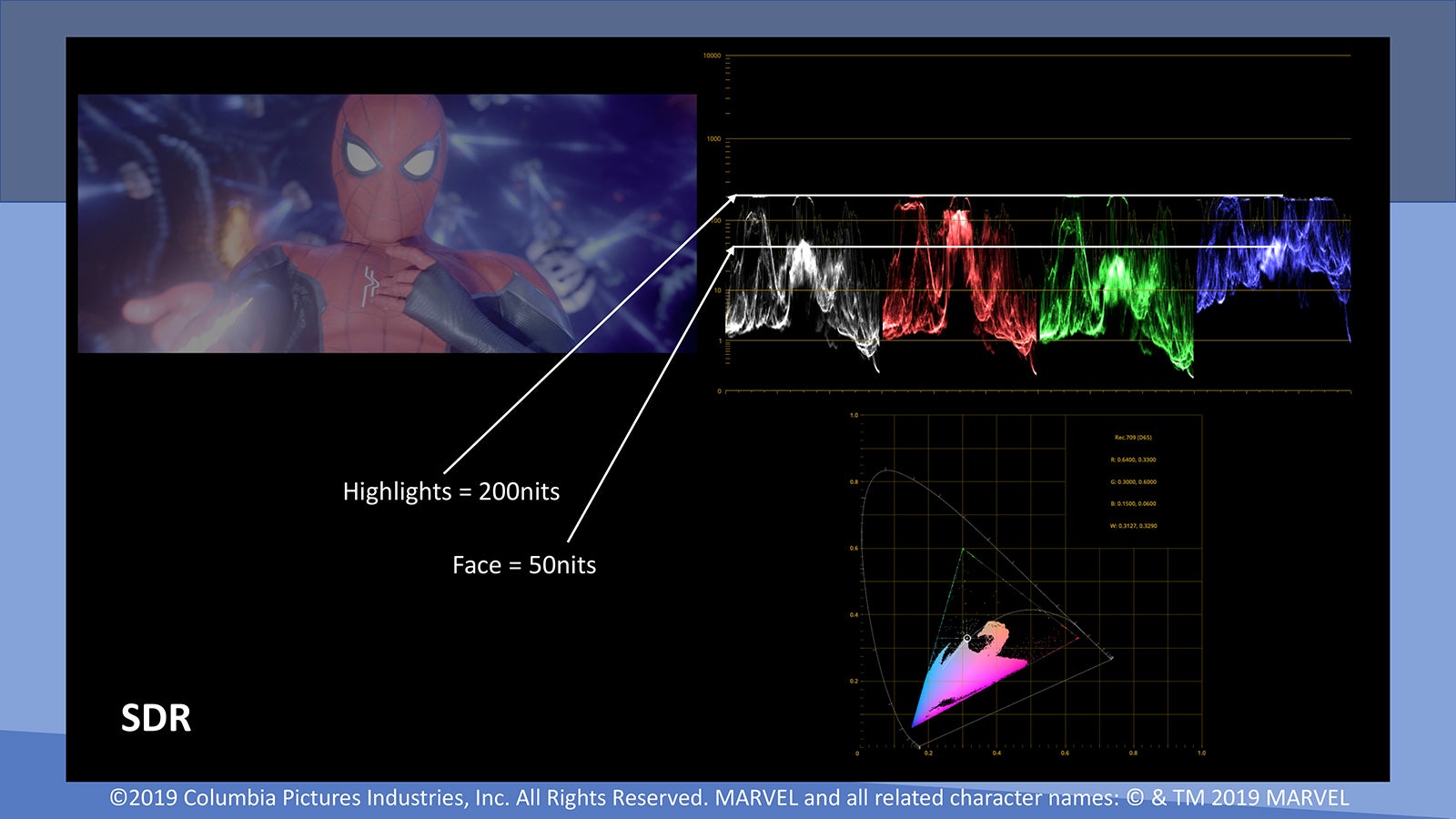

The good thing with skin tones is typically they don't really shift too much in HDR. They're almost at the same level as SDR. There's not a big shift in your mid tone area. It's more in your lows and your highs that really you have to be a little more mindful.

Jeff:

Just to kind of take that one step further. When you're lighting… let's say you want to blow out a window or something like that, this changes that world now, wouldn't you say? Like, if you're trying to blow out a window in SDR, the HDR version would go nuclear.

Bill:

Right, and not just that. More importantly, let’s say something they blew out in SDR because they weren't monitoring it in HDR, they had a flag in a window and you could actually see that in the HDR version. So now, you’ve got to go and blow it out in the HDR version as well or go through VFX to paint out the flag.

It's sort of having that understanding of what's going to happen when you're trying to blow out a window and how do you want it blown out because sometimes it's okay to have stuff outside of a window. Do you want it to feel like you're looking out the window or do you just want a sort of patina of something out there? And that becomes an understanding of how the highlights are reacting with that particular camera that they're shooting on.

And the VENICE and the F65, and even the FX9 - the FX9 has a really good sensor in it. You're looking at something that again is not magic. It's a sensor. It just happens to have this really high dynamic range and you want to make sure that you're appropriately understanding what you're going to get at the end of the day so that you don't stick something in the window assuming that no one will ever see it. These cameras can pick them up and represent them really well. And it's okay, you can get rid of it in post, but better for that be known up front and planned for rather than being a surprise.

DP Brad Lipson doing an HDR grade of the CW show "In the Dark" at Level 3 Post in Burbank, CA

Jeff:

Right, you're seeing that highlight detail that in the SDR version you wouldn't. And then so what about in a grade? If you're going to deliver both SDR and HDR, would you suggest doing the HDR grade first?

Bill:

Always. I always suggest doing the HDR grade first because mentally, it’s hard to change from some of the initial look decisions that are made. If you think about what we've been traditionally doing... So, I shoot on an F55 and I'm going to make an SDR version. I'm going to do an SDR grade, that's traditional television. We've done that for a long time. There are many shows that don't have HDR at all and they're shooting on the F55 and they're doing a traditional Rec709 SDR output. So, it's squashing all this dynamic range from the sensor that we captured down into that 9 stops or 100 nit SDR output.

So, if you start with that, it's much more jarring to go up to what you might be able to get in an HDR grade and you’ve predisposed yourself to certain highlight looks in SDR. If you start with HDR without the preconceived notion of SDR limitations, you are more apt to open up and use the HDR palette. After the HDR grade, once you get to the SDR grade, you're much more likely to realize, "Oh, okay, I can squash my highlights here because I don't want that thing seen out the window, or I like the way it looks there. How do I represent that, to keep that look out the window, but at a much lower level and drive some of the creative decisions based on this bigger palette of HDR colors?"

So starting with a bigger HDR color palette will typically provide a better HDR output. You may be disappointed that the SDR version can’t look exactly like the HDR version, which is exactly the point, but that doesn’t mean that the SDR version is bad or sub-par either. It is a natural consequence of having a much larger color and luminance range in HDR. In my experience with numerous creatives, it has typically been easier to start with a much wider HDR palette and then have to squash it down further into an SDR palette. Whereas, if you started in SDR and you now have to move up into an HDR space, there is much more hesitance to push the highlights as it feels too different from what the SDR version looked like.

Jeff:

What do you think of ACES?

Bill:

I've been involved in the ACES effort for many years. I'm a proponent of ACES. I think that it's a color management system that is accessible to everybody. It doesn't matter what camera you're shooting on, and that's a really important thing. That doesn't mean that the camera manufacturer color management systems are bad in comparison, they're just optimized for their individual cameras.

But when you look at the long-term value of content, ACES allows us to have a more open platform and understanding of what the content is so that 50 years from now, we can bring that material back and hopefully make the year 2070 version of it, whatever that happens to be. I don't know what it's going to be then, perhaps the direct brain chip implant version.

But I know that if we do it in a way that's standardized, then we have a much better understanding of what we can do with it 50 years from now, let alone 10 years from now. Cameras come and go. Their color systems come and go. I fully expect that Sony will be around, but I don't know that the F55 is going to be a camera that people can use. There are specs and documents out there on what the S-Log and S-Gamut systems are but ACES is a long-term entertainment community-supported color management system that has a long-term view on how we maintain our content.

We have some projects that are in ACES, and some in others. I don't look at any one system as a panacea. The questions that we ask are “what do we need to get this particular project done today?” and “how can we best protect it for the future?”. ACES is a very good alternative for a lot of our projects, and it gives us this ability to have a long-term view on the content as well.

Jeff:

A friend of mine shoots a TV show. He's based in L.A. but goes to Toronto for a number of months a year and shoots a TV show for the network. His colorist is out here in Los Angeles and they use ACES. He knows that his colorist is seeing it exactly how it's meant to be seen, and he swears by it.

Bill:

And that's the thing, it's a standardized platform that when you have things set up properly, it is very easy to have the confidence that your friend and his colorist are seeing the same output. And that's definitely a benefit of the system. You can get that in the other systems as well but it may take a little bit more work to get there. ACES provides a standard mechanism for that confidence level. And again, pulling it out of the vault years from now and being able to have the same confidence that the data looks the way it was intended because of a standardized framework.

Jeff:

What are your thoughts on the maturity of HDR?

Bill:

I think HDR is certainly more mature today. As I said, we've been doing this for five, six years now. And the maturity of the systems to support HDR, the maturity of the platforms to deliver HDR and the ability to now start getting either live performance and sports and other outputs in HDR is really a big driver, which is why I've been a big proponent of HDR from the get-go for our library. I think it's been a fantastic boon for us. There is a resurgence in classic catalog titles where we are able to provide it in a way that I think is impactful and meaningful to not just the viewers but to the creative community, as well. Many filmmakers have said, after seeing a classic title remastered in HDR, "I always wanted it to look that way in the past, but I could never get that. That's the way I wanted it to look when we did the video master. That's the way it looked in my mind's eye but on a projector or on a Rec. 709 display. I could never get where I really wanted it to go."

And that's really what we're after, trying to deliver that true creative intent to the people who are consuming our content. And I think the fans of our movies and TV shows agree. It is speaking volumes about how the adoption of HDR is really picking up.