09-05-2023 - Case Study

Shot on VENICE: Jacques Jouffret, ASC brings racing realism to Gran Turismo using Venice 2 and the Rialto Extension System

By: Michael Goldman

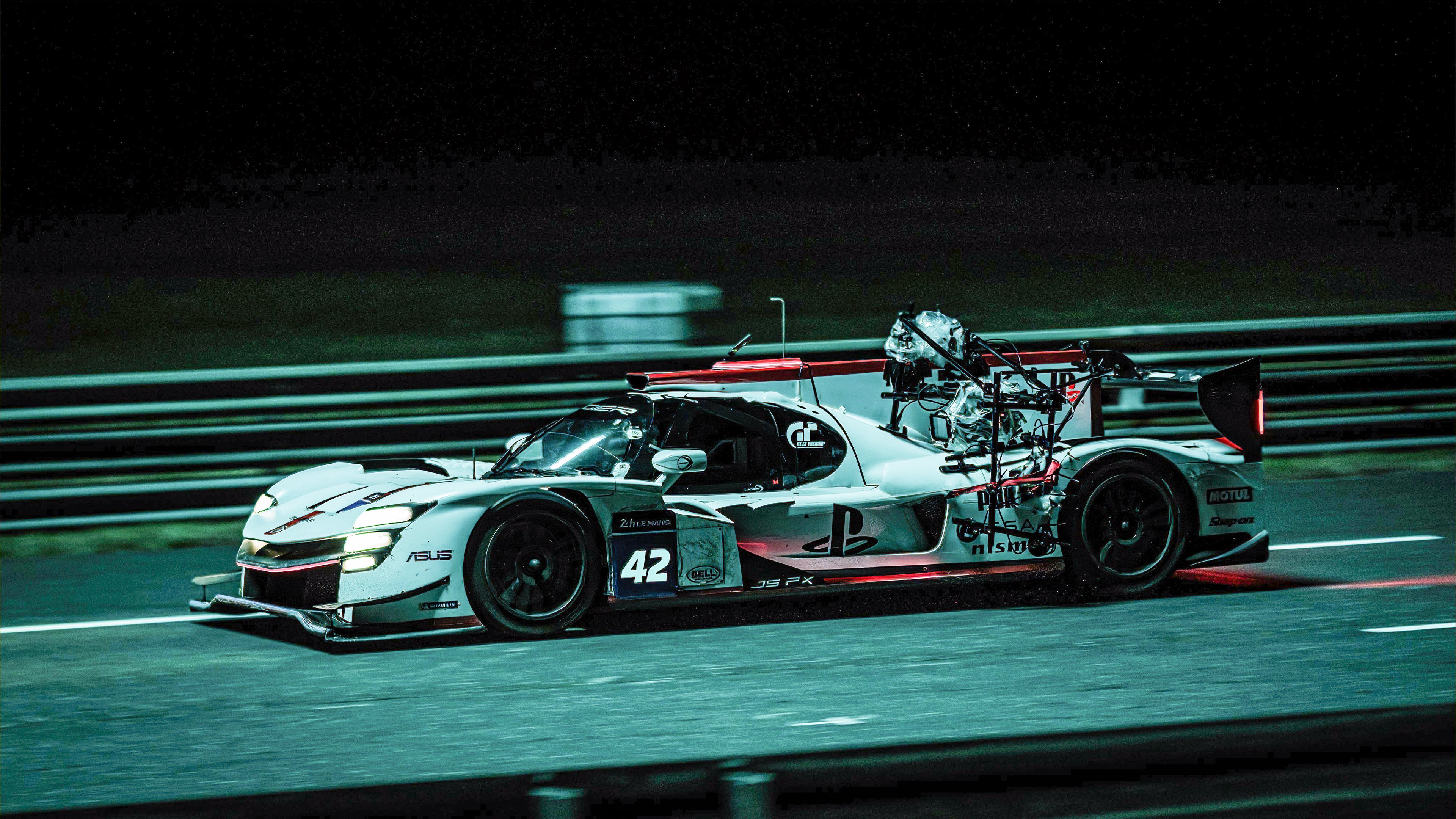

Neill Blomkamp’s new film, Gran Turismo, may appear at a quick glance to be a videogame adaption, but in fact, the movie is nothing of the sort. It’s a character drama which tells a true story about how one young man hopelessly addicted to the race-car driving simulation videogame, Gran Turismo, eventually found a path to use that obsession, and the expert skills he learned playing the game, to not only become a real race-car driver, but a hugely successful one. Indeed, the story of British teenager Jann Mardenborough (Archie Madekwe) is quite real. In 2011, Mardenborough’s sim-game performances were strong enough to qualify him for the GT Academy project—an ongoing (at the time) real-world competition sponsored by Nissan, Sony’s PlayStation, and Polyphony Digital for gamers who excelled at Gran Turismo to be trained as real race-car drivers, with the Academy’s top driver each year earning a chance to qualify for a racing license on the European circuit. Mardenborough eventually started placing and occasionally winning on the circuit to the point where his Nissan team eventually made the podium at the 2013 24 Hours of Le Mans race.

Blomkamp’s Vision for Gran Turismo

When Blomkamp decided he wanted to make a movie about Mardenborough, he insisted the film’s racing sequences appear as real as possible. To that end, he enlisted cinematographer Jacques Jouffret, ASC, to figure out how best to achieve that goal. Jouffret immediately decided the only way to get to ultra-realism was to utilize Sony’s VENICE 2 camera in combination with the new Rialto 2 camera extension system in order to separate the body of the camera from the camera’s 8K sensor and lenses inside real race cars.

“The big thing was that the racing had to be realistic,” he says. “The first thing Neill told me was ‘I want it real, nothing faked, cars going full speed, no greenscreen or bluescreen, with the actors in the cars.’ He referenced the film Le Mans [1971], which captured how violent the sport of race car driving is. We wanted multiple cameras to try and capture this reality.”

To make that happen, it was essential to shoot real race cars on real major tracks across Europe with the ability to have cameras inside cockpits. The problem with that, of course, is that race-car cockpits are not built to hold more than one driver. Jouffret, however, recalled that his colleague, Claudio Miranda, ASC, faced a similar challenge filming Top Gun: Maverick a couple of years ago when his team inserted the original VENICE and Rialto camera systems into the cockpits of modern fighter jets.

Go behind the scenes: https://youtu.be/5mjd14G9wyE

Rigging the Rialto Extension System

“The fact that Neill wanted to shoot inside real cars at real speeds was a similar situation to the one Claudio dealt with,” Jouffret explains. “So, I talked with his first AC, Dan Ming, who explained to me their methodology in detail. I took that methodology and applied it to using a Sony VENICE 2 and prototype Rialto 2 Extension System. This way, we were able to put camera sensors and lenses into the cockpit and the recorder in various places outside the cockpit. We configured three Sony Rialto 2 systems inside cockpits—one between the controls, facing the driver, one on the left, and one on the right, stretching for a bit of a different, wider angle. This allowed us to capture images that would complement the other cameras outside on the track for editing. This let editors cut from a camera on the left side of the vehicle into the cockpit, and then go outside the car again using the camera that is on the correct side for a smooth transition.

“In addition to the three cameras inside the cars, we had cameras hard-mounted outside, on the wheel well, forward and backward. This was all designed to capture as much material as we could every time the cars got onto the track.”

The cinematographer points out this methodology allowed his team to meet one of Blomkamp’s key requirements—“framing and composition was very much about removing any elements in a frame that did not give you a sense of speed. I told my operators to limit the sky and show elements that give a sense of speed. That is one thing you will notice right away—there is lots of tarmac [visible] on the ground compared to the amount of sky, because the tarmac enhanced that sense of speed. Our main tracking vehicle used a remote head very close to the ground to capture the tarmac at high speeds—no stabilization at all, as we wanted a sense of vibration.”

Jouffret also emphasizes that “these are not cars that can just stop and go whenever you want [another take].” That meant his team had to strategically place cameras all around the track in key locations to capture imagery from the track, the pit perch, the pit box, the pit lane, and so forth. “It wasn’t just the racing we had to cover, but also cameras in various places catching drama and action in other places.”

He elaborates that operator Nino Pansini took charge of outfitting the production’s Nissan GTR camera car that tracked the racers—not exactly the kind of vehicle typically used for movie-making.

“Since Neill wanted the cars going at full speed or very close to it, the first question I had was how to find a camera car that could keep up,” Jouffret explains. “We finally found someone in the UK who had an operational Nissan GT-R vehicle. It was the only vehicle we had available to us that could keep up with the race cars—barely, because the tracking car had to deal with the weight of all those cameras. Then, I had one vehicle on the perimeter—the service road around the tracks—and a Russian Arm that was mainly used for shots on the perimeter or doing counter moves to give us a different perspective.”

All told, Jouffret says the production utilized six Sony VENICE 2 cameras in various combinations with three Rialto 2 extension systems. (Five RED cameras were also employed for additional drone imagery). For lensing, Jouffret relied primarily on Panavision Panaspeed Primes (F1.4) for the bulk of the production; along with two Primo 70 zooms (F3.5) on tracking vehicles; and an Angenieux 12x1 zoom (F4.5 with a 1.4 extender) for long-lens footage. Additionally, a set of Leica Summilux lenses (F1.4) were used for interior car work, connected to the Rialto 2, and some specialty lenses were mixed in for specific POV’s like engine insert photography.

Jouffret hastens to add that the VENICE 2 system’s superior ISO capabilities were crucial.

Choosing the Sony VENICE 2

“A big thing for me was the fact that the VENICE 2 is an 800 ISO camera,” he says. “Obviously, that gave me a lot more dynamic range. More importantly, you can go to 1600 ISO or 3200, and the color rendition at those different ISO’s is incredible. You can shoot at really low exposure and still get a perfect rendition of color. I felt that was important for me, being in a situation where we would have to work with the elements. We had a lot of night scenes, and there was little chance for me to do different lighting in all those situations. So, we had to ride the exposure, going often from overcast to sunny, depending on the day and what part of the track we were on, yet we could still make sure dynamic range was correct.

“For day work, I basically went with natural light. The biggest challenge was in balancing the interior of the cockpit with outside exposure. So, inside the cockpit, besides the cameras, we were able to use small LED lights on the driver. That, in turn, was challenging because I had to put an ND filter on the cockpit. That’s tricky with a sports car, which has a concave windshield. So, I had a specialized team that would gel the NDs and steam them onto the windshields, to better balance things for interior and exterior exposure. That was always a difficult decision, since the weather could change so rapidly—we had to decide where the exposure should be before we could put all the cars onto the track.”

Jouffret adds that the unique nature of capturing realistic auto racing posed other special lighting challenges for himself and gaffer Paul Postal. The almost four-mile-long Le Mans Mulsannes Straight is one key example. On an airfield tarmac, filmmakers set up 12 large construction cranes with 12 20x30 softboxes on each, with each softbox relying on 28 Creamsource Vortex 8 lights. “We wanted to make sure that we had maximum color control and weather protection, since the Vortex lamps have an IP65 (water-resistant) rating,” he explains.

Managing the digital workflow

In terms of workflow, digital imaging technician Felix Rauch managing a fiber-optic system setup around the various tracks. Typically, the range of that system was about a mile in terms of controlling exposure, according to Jouffret. “There is a limit to the transmission from the DIT to where the camera is,” he explains. “We couldn’t afford a system that could cover an entire track, to give me full control of exposure around the track. After about a mile, we would lose it and have to wait for the car to go around and get back within range of our antennas. However, I was so satisfied with the dynamic range of the VENICE 2 that I was always more or less in the right location in terms of exposure.”

Colorfront Budapest handled the dailies, while the final color grade was done by Company 3 in Los Angeles under the supervision of Stefan Sonnenfeld, that company’s president/CEO and senior colorist.

Gran Turismo: Based on a True Story is in theaters now.