12-27-2021 - Case Study

The Camera Operator / DP Relationship – Part 1 – Communication and Going Again

By:

Steven Bernstein:

Hi, my name's Steven Bernstein. I'm honored to be here with a legend from our field, someone who has not only worked on some of the most important and largest films of the last twenty-five years (Die Hard, Scarface, Conspiracy Theory, Mission: Impossible III and many others) but is highly regarded throughout the industry for his expertise and his character. The man I'm talking about is Mike Ferris from the Society of Camera Operators. We will be talking about the relationship between the cinematographer and the camera operator, which is more varied, rich, and complex than people might realize looking at it from the outside. Michael, first, thanks for joining us.

Michael Ferris:

My pleasure, Steven. Delightful to be with you.

Steven Bernstein:

So, what does a camera operator do?

Michael Ferris:

In the strictest sense, the camera operator makes real the vision of the director and the DP. He puts it into physical, visual, practical reality.

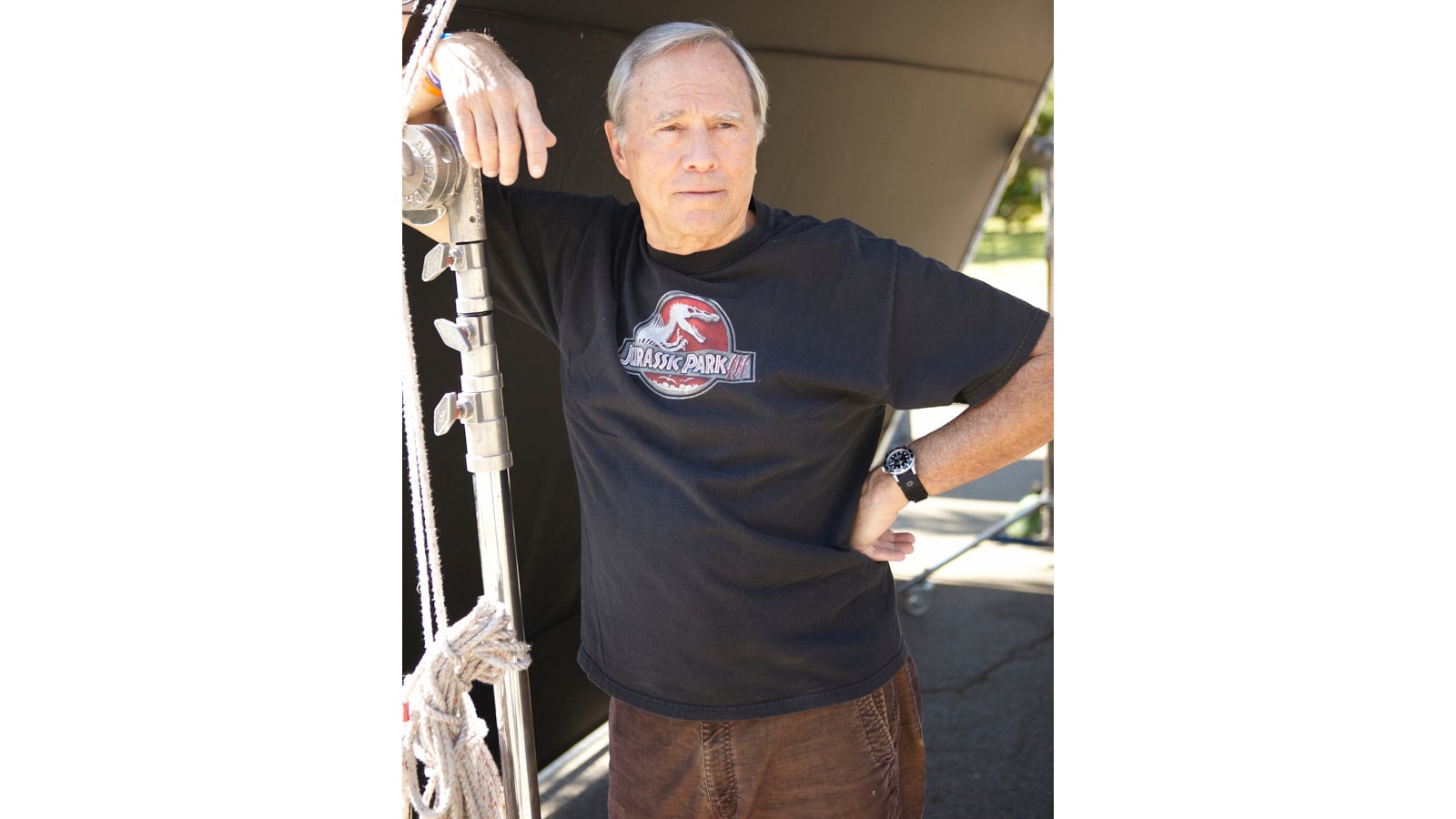

Michael Ferris, SOC in gloves on set with Steven Bernstein, ASC, DGA. All photos Jeff Berlin

Steven Bernstein:

There are a lot of young DPs who operate themselves and some older ones as well. Why shouldn't DPs just operate? What's the advantage of having a camera operator?

Michael Ferris:

Well, you're going to get a lot of different opinions on that, but I think it evolved naturally, the way good things do. A DP has so many things to take care of. If he has an extra set of eyes, a camera operator, he is that much ahead of the game. If he has a camera operator where there’s mutual respect and the same taste, he is much further ahead. Also, the camera operator is the second in command, and he leads the crew. The DP really leads the crew, but the operator takes a lot of that off the DP's shoulders to deal with all the other aspects he has to deal with. He must deal with the director, every department head, the producers; he must deal with everything. The more of the physical setting of shots, rehearsing shots, and making it happen that an operator can do, can be essential to the value of a film.

Steven Bernstein:

Also, if you're doing one job, which is getting the shot right, you're probably going to do it well. Whereas if you're thinking about lighting, politics, the director, the crew, the schedule, you may not be able to focus on the shot, and you may miss something. So, the idea is that the operator focuses entirely on the shot and, therefore, will get it right. Am I right in saying that?

Michael Ferris:

You're right, and that's another essential aspect of the job. The DP, as I say, has so much to do, and politics is a big part of it. But what I mean is the politics of personality, a vision of creativity, which comes down the line from the top. The director and producers can get very involved, but once the shot is blocked and you're beginning to get a sense of it, the operator takes the crew and makes the shot happen. He rehearses it. He plans it. If he sees somebody out of his light, he and the DP discuss it, they fix it, but it allows the DP to stand back, look at all of it, and see what he likes and what he doesn't like. And when it's time to go, because time is money and money is what movies are all about in many ways, it makes it possible to stay on budget, stay on schedule and keep the machine moving.

Steven Bernstein:

Absolutely. Now you've worked with both British cinematographers and American cinematographers. The relationship between the camera operator and the cinematographer is different in a British film than in an American film. Is that right?

Michael Ferris:

It is right. The styles are different. The British DPs tend to do the lighting and leave the operating to the operator. American DPs want to be more involved with the shot-making itself. A camera operator understands these things and will fill in or back up as they need. The key to being an operator is to be adaptable, communicative, and super aware. This means when I see something that's the slightest bit out of place; alarms go off in my mind. You have to gain a lot of experience before this becomes natural. But when it does, you're an invaluable piece of the machinery.

Steven Bernstein:

Now, when you're looking through the viewfinder, there are various lines, witness marks, that tell us what our frame's going to be. What you see through the viewfinder is more than what the camera will ultimately project on the screen. So, you're looking at all those different marks and deciding what will go in the frame. What happens when a boom is in the shot, or they're throwing shadows in the back of the shot?

Michael Ferris:

Well, we stop and fix it.

Steven Bernstein:

How do you fix it?

Michael Ferris:

It depends on the DP and how he's lighting. I would say, "We have a little problem over here. We're moving in this shot." The operator's job is to announce that to the DP, and then he can flag it off.

Steven Bernstein:

Talk to me about the relationship between the camera operator and their assistant. Things to do with focus and when the camera operator says my favorite expression, "I think I got it."

Ferris on set with actor Maggie Grace.

Michael Ferris:

One of the keys to my success, my reputation, and becoming sought after is all about assistants. Assistants, first of all, I believe they're the backbone of the industry. They do the heavy lifting. They do the most challenging work, following focus, keeping that camera going and moving, and doing it on the fly when you're doing fast moves or slow. The responsibility of an operator is to see the shot, but if something goes fuzzy or soft, almost always, it's the camera assistant who gets the blame, but they can't see the shot. It's the operator that sees everything. So, if a shot goes wrong, focus-wise, you just cut, but you have to be careful about it. You have to know your circumstances, situation, and personalities, but then you go and do it again, and make sure it's right.

Steven Bernstein:

Such a critical point, and one that you taught me, that one extra take to get a shot in focus is better than the unusable shot. Of course, the great dilemma for a camera operator, cinematographer, and the director is conjoining different elements. Not only the performance being perfect, but the shot being perfect and the focus being perfect. So sometimes a director or a DP would say, "That shot was beautiful, the little push in the end and the performance was fantastic," and then the camera assistant would sheepishly say, "I'm not sure I got it."

Michael Ferris:

Or the operator.

Steven Bernstein:

Well, hopefully, it'll be the operator. I have been guilty of saying, "Are you sure?" Which is the stupidest question to ask because it doesn't matter whether they're sure or not.

Michael Ferris:

If there's doubt.

Steven Bernstein:

If there's doubt, everything should stop because focus can't be fixed.

Michael Ferris:

No, focus can't be fixed. When you do big features, if you see something going wrong, it's your job, it's your responsibility to speak up, and if the DP or director decides to move on, then you've done your job, and you move on. Also, big shows think nothing of coming back and re-shooting. That's something I remember being amazed about when I got out of the smaller productions into the big world. They didn't hesitate unless you had five helicopters flying under bridges.

Steven Bernstein:

So, if something goes wrong, you feel it's incumbent on you to say to the cinematographer, "I'm not sure we got it. Let's do another take." And as much as the cinematographer may want to rush along, it's better to stop and do it again. How do you communicate issues with lighting or something not working to a cinematographer that's both supportive and diplomatic?

Michael Ferris:

I think of the different personalities I've worked with over the years, and they all vary so much. When I did Scarface, the relationship was pretty much between Brian De Palma and me. For seven months, there was no monitor. Now, the DP, John Alonzo, saw and knew everything that was going on, but he trusted me at that stage in our relationship. So, at the end of a take, Brian would look at me and say, "Mike," and if I hesitated, it was, "Go again."

Steven Bernstein:

You had no monitor because this was before monitors were available?

Michael Ferris:

No, no. Jerry Lewis invented TV monitors in 1962. They were just not used. Brian De Palma was old school and didn't believe in them. He also made many movies and was very confident in his ability and the people he surrounded himself with.

Steven Bernstein:

When I first started, the operators I worked with in England were old school and resented anyone suggesting they have a monitor.

Michael Ferris:

Yeah.

Steven Bernstein:

So, they would shoot something, and I would ask them after, "How was it?" And they would say it was good or there wasn't enough headroom, or it should be a little bit to the right. We weren't seeing what they were seeing; we were just hoping they told us the truth. That's how you began as well. You had so much more pressure on you to get it right.

Michael Ferris:

Well, it's pressure, especially when you're starting. Keep in mind, there's no school for camera operating; there's no school for assisting. These are things that you must care so deeply about that you find a way to get the experience. Now, you need mentors and people who help you. That's why there's a hierarchy, which goes back to your first question about DPs who operate.

John Alonzo on Scarface controlled the set with an iron fist. You didn't make suggestions out loud. The way I would communicate with John was I would slip over to him and whisper in his ear that there was a possibility the light up in the rafter would be seen as we moved on our dolly track. He didn't say a word to me. He looked and went back to what he was doing. But then he talked to an electrician, and that light got fixed or moved. He insisted on that, and he never sat down with me and said, "This is the way I work." That was my job to figure out. When I figured it out, that's when I became his operator. But also, if I got off the camera and went to John instead of talking directly to Brian, there was something bigger that had to be dealt with. You have to develop a relationship with each DP, and when you rise to a certain level, you go off and work with strangers, but the key part is getting to know the people you work with and for. Confidence is easy once you've done that and have 10,000 hours of experience.

About the author:

Director / DP Steven Bernstein, DGA, ASC, WGA is an ASC outstanding achievement nominee for the TV series “Magic City.” He shot the Oscar winning film “Monster,” “Kicking and Screaming,” directed by Noah Baumbach, “White Chicks” and some 50 other features and television shows. The second film he wrote and directed, “Last Call,” stars John Malkovich, Rhys Ifans, Rodrigo Santoro, Zosia Mamet, Tony Hale, Romola Garai and Phil Ettinger, released late in 2020 sinto theaters in selected cities. "Last Call" is now streaming on Amazon Prime.

Steven can be followed at Stevenbernsteindirectorwriter on Instagram where he regularly posts short insights and illustrations about filmmaking.