12-13-2021 - Case Study, Technology

The DP / Colorist Relationship – A Conversation Between Jill Bogdanowicz, Co-Head of Features Color at Company 3 and Steven Bernstein, ASC, DGA

By:

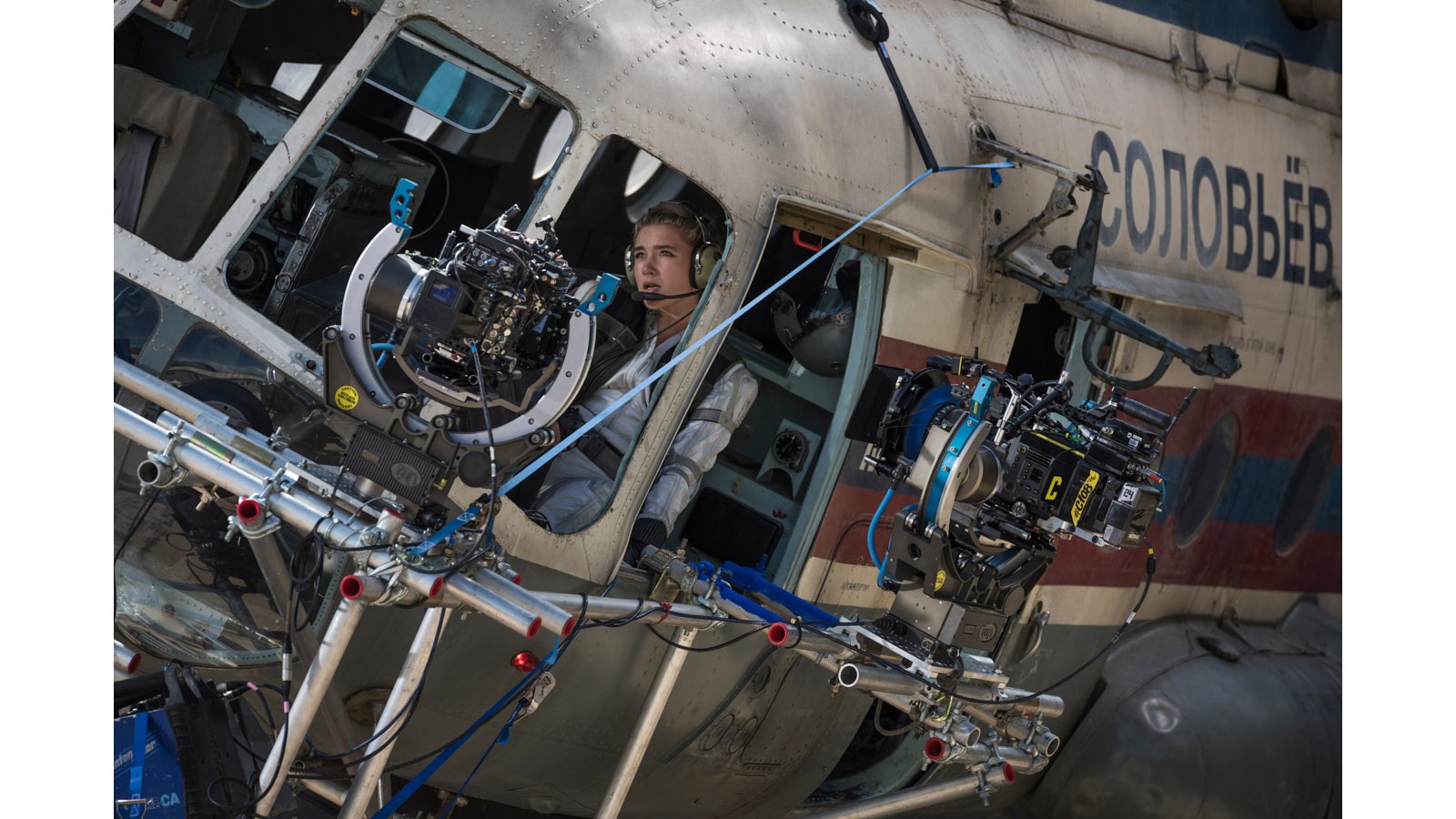

Jill Bogdanowicz, is a celebrated colorist based at Company 3 in Santa Monica, California. She was among the first colorists to employ digital grading tools to color major theatrical feature films. Since joining Company 3 in the fall of 2014, Bogdanowicz has brought her unique talents to features including Black Widow, shot on the Sony VENICE, Joker, Spider-Man: No Way Home and Far From Home, John Wick: Chapter 3 and Chapter 4, and series including The Umbrella Academy. She took home the 2021 HPA Award for Outstanding Color Grading in the Commercial category for her work on “Jessica Long Story: Upstream” for Toyota. Click link above to read full bio.

Jill Bogdanowicz

Steven Bernstein, ASC :

When you are working on a DI (Digital Intermediate), do you prefer that everything is invented once people arrive at your door, or do you want bunches of notes from the cinematographer, or is it a hybrid?

Jill Bogdanowicz:

Well, it is actually much deeper than that. Usually, what I will do on most of my shows now is get involved in pre-production. So, I'm doing hair and makeup tests with the cinematographer and helping create the Lookup Table for the show right from the outset.

So, when the filmmakers decide to get me or some other colorist involved from the beginning, usually by the time we get to the DI, all of the "look" decisions have already been made or talked about, and the colorist has been part of those conversations.

Ideally, these decisions about the look happen early on and then are carried through the whole process so all of the dailies that the editor sees, and the producers see, and everybody involved sees, are the same as what will eventually be released in theatres or on TV. In other words, everybody will be looking at something that is a pretty good representation of the visual intention of the director and cinematographer. In this way, everybody is on the same page.

Also, for the big shows that have visual effects, the effects teams will need to know the look of the film/show before it gets to the final, and they have to create material that will match everything else. They can do this if a look has been established already with a colorist. So, the colorist isn't (or shouldn't) only be at the very end of the process.

Steven Bernstein, ASC :

For a long time, we talked at the ASC about developing a method to have a visual through-line, a DP creating a look and making sure it remains through shooting and right through post. Every DP thought that was very important. Otherwise, the look could change at each stage by introducing a new artist, producer, or technician. So, let's talk more about that. Are you working with the DITs, with the cinematographers, or with production generally? You mentioned visual effects; that's super important. Effects have to match what the main unit photographed and produced. If it doesn't match, the effects fail. So how does this all work?

Jill Bogdanowicz:

I usually work with the cinematographer, and if there's a DIT, I will be working with a DIT and a dailies colorist. So, I make sure that both the DIT and the dailies colorists are on board with the agreed look and are using the correct Lookup Table so that everything is looking the way it should from the very beginning. Usually, the DIT and or the dailies colorist will design something called CDLs, which are very simple color corrections that go along with the LUTs throughout the process, so there is consistency and uniformity. These also go to the visual effects team so that the visual effect workers can see the look that everybody's been seeing in dailies. So, they, too, are on board.

Steven Bernstein, ASC :

So, that means when a DP is on set and the DIT's putting something on a screen, presuming that screen has been pre-calibrated, it will match what everyone will see from that day until the release of the film/show in the cinema or on TV. Also, the DP and the director will know exactly what to expect when they come to see you in the DI, yes?

Jill Bogdanowicz:

Almost. There are things to consider with color space translations. For example, I have to deal with another factor at play: whether the production has been working in 709 or P3 or HDR on set. So sometimes what they're looking at onset isn't exactly what I will see, but I have a wonderful color science team that will make sure that look will match as closely as possible.

Steven Bernstein, ASC :

Color science is important. Every monitor, every system through the workflow will take the same data and produce potentially different images. In the past, when a DP was trying to communicate to a colorist, they'd be sending still photographs (digital or polaroid), things from completely different color spaces. They might include some written notes. But images are so complicated with so many elements that this method would never get the exact desired result try as the colorist might to get it right. Getting the colorist involved earlier is better, but DPs are still sometimes forced to work in this other way on lower-budget films. It's hard for the DP and hard for the colorist. It's not precise. Is there a way to work with this data if nothing else can be made available?

Jill Bogdanowicz:

Well, the dailies will be of interest, and their DP's ideas will be useful as well, but really, we will sort of be starting from scratch in post. We have to find an agreed-upon vision. So I might say to the DP or the director, "You know what, we could try this or we can try this," or, "What you did in dailies was cool, I understand what you're going for, but maybe we could try it a different way to be able to make it technically more solid" or I might make a suggestion about what could be converted into the color space I am using more efficiently.

Because we are dealing with images, it's a matter of showing the DP (and possibly the director) images rather than describing them. When I get an idea of what they are trying to do, I can then visually show them my take on that and hopefully get it to something they respond to.

Of course, the other consideration is that the material will not end up in a single-color space because it's not just going to the movie theatre or TV anymore. Now that all these deliverables are in different color spaces, like HDR, Rec 709, and many more. So even if I am involved with the Lookup Tables from the beginning, there is still a lot to consider and change later. Also, if I get a Lookup Table that I wasn't involved in making and I don't know where it came from, I have to run it through its paces.

Steven Bernstein, ASC :

I think it is quite fascinating how much "translating" of the color image you have to do because the material is to appear on a big screen, but also television and now on a telephone or mobile device and a bunch of other places and in so many different formats.

Jill Bogdanowicz:

Yeah, but it's doable. There are two steps to the process. We've got color science that helps do the overall translation for us, which is beautiful, but then there's the perception of it. Everybody's perception is based on whatever display they're looking at. The perception is arguably more important than the objectively technical because it is what the viewer will experience. Figuring out how someone experiences a small screen differently requires creative imagination; it is a creative process.

Steven Bernstein, ASC :

Creative. Exactly. Really you are an artist very much in your own right, like the cinematographer or the director. With several creative artists working together, it can get complicated. How do you navigate these relationships? Because you're so experienced and your background so remarkable, they might be a little intimidated when a young DP or a young director comes to work with you. How do you develop a rapport with them?

Jill Bogdanowicz:

I always say that 70% of my job is psychology. It's just being able to understand a filmmaker's intention. So, yeah, I look at their references, look at their inspiration. Maybe it's an artist, or a photographer or another film. I look at their lighting to see what they are trying to achieve and understand why they made the choices they did. I look at their camera and lenses to figure out their thinking as regards the visual. I will try to figure out what mood or feeling they were trying to evoke while shooting. I also really like to know the story of the film; it all starts there, and I like to know what inspired the choices in the storytelling. This helps me get inside of the mind of the creatives that I'm working with, and then I can help support their vision.

Then it's a matter of building the creative bridge; I can show options and pitch different ideas based on my experience. It's fun, as every movie is different, and every dynamic is different. It's really never somebody coming in and telling me verbatim what to do on the controls; rather, it's somebody coming in and saying what feeling or what emotions or what vibe they want to see on the screen, and then I can help get them there, and I really enjoy that.

Steven Bernstein, ASC :

That's a great note because leadership has often to do with inspiration rather than someone trying to tell you what to do; they need only explain their vision, even if that vision isn't fully formed. It can be as simple as saying, "This is what inspired me, how do we get there?" Letting others into the creative process, learning to collaborate, even with someone as vastly experienced as you, I would say PARTICULARLY with someone as experienced as you, is essential. Share the vision, but don't instruct on the method as to how it can be achieved.

Going back to something you said, let me ask how you explain to young directors and DPs how their work will appear in different formats and color spaces? I suppose they are inclined to think the ideal image they see on the big screen with the colorist is all that matters. But only a small percentage of their audience might ever see the film in ideal circumstances.

Jill Bogdanowicz:

Absolutely, yeah, sure, there are different variations depending on what theatre you go to, depending on your TV at home. I've run into that many times where people's TVs have not been set up correctly. There are quite a few different variables there, so I do always try to explain to every filmmaker that I'm working with what the variables are and why I color things in a certain way to be able to almost make a "thick negative" as they used to say in the all-film days; (NOTE: a "thick-negative" film was well exposed so it could be manipulated later without an increase in grain). So, I produce something that will hold up really well on all the formats and variables we know exist.

Steven Bernstein, ASC :

You mentioned visual effects. Effects can be produced in post. They can be generated by computers, maybe with 3D compositing or a variety of other techniques. But they have to match what the main unit produces. How do you control this? How do you communicate with the effects people?

Jill Bogdanowicz:

Every show is different. So, I'm there for whatever anybody needs. I make one LUT per show in general. It's like choosing a film stock for your movie. You do one LUT, and then you have CDLs, which are smaller color corrections that happen shot per shot and will follow throughout the whole process. After I have created a Lookup Table with a cinematographer and DIT, and maybe the director, the visual effects team will be given that LUT and do all their work with that reference.

This is important. It's possible I might be doing something in the Lookup Table that is destructive to visual effects; maybe, for example, it makes their keying more difficult. But if the effects team has the LUT information from the outset, then that type of thing can be addressed early on. To be honest, I have been doing this a long time, and I know the limitations; and I've got a color science team that always double-checks any Lookup Table I make to ensure that there's nothing in it that would cause visual effects any issues. But if someone is not using me as their colorist or is using a different facility, these things must be checked and checked early.

Steven Bernstein, ASC :

Some DPs have their DIT make many different LUTs. Every scene has a different LUT. What's your view on that?

Jill Bogdanowicz:

LUTs don't follow along with the EDL (Edit Decision List), so it's a manual process. A DP who gives me an old-fashioned list like you describe, I have to ask, "which LUT did you use on which scene?" Because I will have no way of knowing.

Steven Bernstein, ASC :

That's a big problem.

Jill Bogdanowicz:

There's no automated process at the moment, there are certain tools that try to automate it, but it's really not an automated process quite yet. That's why I prefer using one Lookup Table, which creates a more uniform look anyway. I have not found anything that I couldn't achieve, even with some pretty extreme looks, by using one Lookup Table and seeing CDLs.

I should say that I will occasionally use different LUTs, like if it's a black and white LUT or something very extreme. But generally, I try to keep it to just one LUT. If I have to use two, we use two, but one LUT is best for the workflow. This is not to say it isn't possible to use multiple LUT's, but the inability to track them through (or track manual notes if that is provided) makes for a workflow that isn't very smooth.

Steven Bernstein, ASC :

Now, you go to a really important point: how much time people spend in the DI. On a major film, a lot of time may be budgeted for the DI. But on a smaller budget, a production may not be able to afford a lot of time in the color grading suite. So, what time that is available has to be used efficiently.

Jill Bogdanowicz:

That's exactly right. So, in one sense bringing in the colorist early seems to cost more. Still, if there are any issues or anything that needs to be brought up that a producer, director, or cinematographer can fix or improve, in that case, it can be addressed earlier rather than later. Then everybody can be on the same page, making the film go faster and much smoother.

Part Two Coming Soon

About the author:

Director / DP Steven Bernstein, DGA, ASC, WGA is an ASC outstanding achievement nominee for the TV series “Magic City.” He shot the Oscar winning film “Monster,” “Kicking and Screaming,” directed by Noah Baumbach, “White Chicks” and some 50 other features and television shows. The second film he wrote and directed, “Last Call,” stars John Malkovich, Rhys Ifans, Rodrigo Santoro, Zosia Mamet, Tony Hale, Romola Garai and Phil Ettinger, released late in 2020 sinto theaters in selected cities. "Last Call" is now streaming on Amazon Prime.

Steven can be followed at Stevenbernsteindirectorwriter on instagram where he regularly posts short insights and illustrations about filmmaking.