03-29-2021 - Case Study

The DP - Gaffer Relationship - A Conversation - Part 1

By:

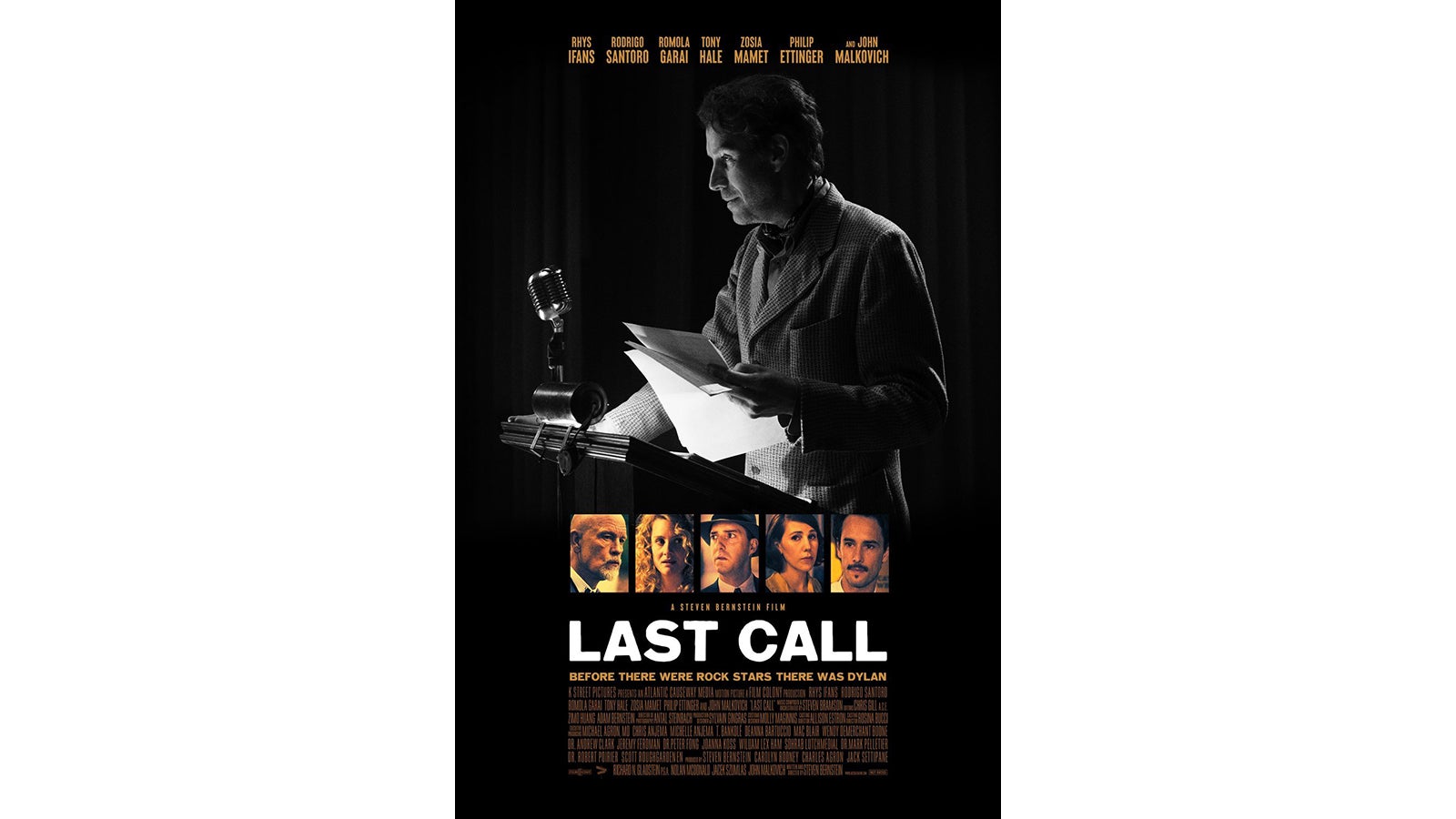

Writer, director and DP Steven Bernstein, DGA, ASC, WGA and DP and gaffer Antal Steinbach discuss the DP / Gaffer relationship in the context of their collaborations on Magic City and more recently, Last Call, a feature film written and directed by Bernstein and starring John Malkovich. Steinbach was DP of Last Call.

Steven Bernstein:

I'm a screenwriter, director and I was a cinematographer for a long time. My new film Last Call with Rhys Ifans, John Malkovich, Romola Garai, Rodrigo Santoro, Tony Hale and Zosia Mamet was recently released in theaters in the USA. We shot most of it in Montreal, Canada although the events of the film take place in New York City and Wales. I knew that it would be impossible to be both the director and cinematographer on my own film, so I hired who I felt was the best person for the job. Antal Steinbach was someone who had worked for me in the past as my gaffer on the second season of the TV series Magic City.

Antal Steinbach:

Thanks Steven. We had a great time on Magic City.

Steven:

I think you had worked on the series as the rigging gaffer before I joined the show.

Antal:

Yes. I had been working as a gaffer and a cinematographer for many years mostly on commercials. I live in Miami, where the show was shooting, and was offered the opportunity to work as a rigging gaffer. The show was a very big show for Miami. For the first season I worked closely with the director of photography Gabriel Beristain and the first unit gaffer. It was a big responsibility because on the first season there was only one cinematographer and there were rotating directors. We had a pretty intense schedule.

Steven:

Can you explain what a rigging gaffer does and what your job on Magic City entailed?

Antal:

You want to get ahead of the game. So, my job was to pre-rig or prepare a set for the main unit so that when they arrived it was virtually ready to shoot. Everything from laying cables, to getting the lights into position. That’s basically what a rigging gaffer does. On Magic City because of the schedule, I was asked to do as much pre-lighting as I could as well. On the first season, because there was only one DP, who would be shooting every episode with the gaffer, I would go on the tech scouts with the director. I would take notes about what the director wanted and then consult with the DP and the gaffer about what was coming up on the next day, the next episode's location and so forth and figure out how we were going to shoot it. I would get everything as close to being as ready as possible because most of the time the unit would arrive at a location without ever having seen it. The DP would come into a location having only seen the pictures and drawings I provided him. He would need to be ready to shoot in not much time. So that was really where I cut my teeth in narrative. It really was kind of a trial by fire. It was a lot of responsibility. Luckily, I had a great crew and Gaby gave me a lot of trust early on which gave me the confidence to just go with my instinct and do as much as I could to have it prepared for them.

The scheduling became easier when you came to work on the second season and we had rotating DPs.

Steven:

I think the relationship between the gaffer and the cinematographer is a very interesting one. So, what do you feel that your job is in relationship to the cinematographer? What can you tell me about that creative relationship? Does the cinematographer say, I want it to look pretty and you make it pretty, or I want it to look shady or grim or frightening and then you try to achieve that? Do you prefer to be directed or do you prefer for the DP to just say make it look great and you just go ahead and do it?

Antal:

Well like any relationship they're all different. Personalities and creative processes are very different from one DP and one gaffer to the next. Luckily, the relationships I had with you on Magic City were very collaborative. TV is very fast paced. Whether it’s big budget or not, you're shooting a lot of pages a day. You have to be ready when you have to be ready. You have to make decisions and kind of live with them because once you're in it there’s no time to re-do much. I think trust and collaboration between the DP and the gaffer on a TV series is essential because of the sheer amount of responsibility the DP has.

The DP is often dealing with a new director every episode which I’m sure is a very daunting task, so, I think having a gaffer whom you can trust must be a great comfort. I've also done other jobs where my job is more about coming up with and executing creative solutions to save time. A gaffer often has to be thinking one step or several steps ahead to be more efficient. So, it definitely varies.

As you know, I’m working more as a DP now and for me having a gaffer who I can trust, who understands the way I work, is a huge help. It allows me to deal with all the other things I have to deal with like working with the director, managing the crew, thinking ahead about other locations and scenes etcetera.

Bernstein, right, on the set of Last Call

Steven:

I think you are right. And I think for me one of the big lessons that one learns as one moves up the ladder in the film industry is although the inclination is to want to draw attention to yourself, in fact, the best thing you can do is learn to delegate. This means you have to trust the people you're delegating to. Because we're freelancers, people want to draw attention to themselves and say, “look how great I am,” because they think it gets them work when, in fact, what really gets you work is when the film or the TV show you're working on is successful. And for that film or show to be successful requires good management. Good management is based on good delegation.

On Magic City, for you and me, it was particularly important because we were thrown into it together. We didn't have a prior history of working together. When I came in, you'd been there already but in a different capacity. We ended up getting the ASC Awards nomination for outstanding cinematography for one of the episodes we did together which, considering the level of competition for the ASC award, is a very high tribute indeed. And we would not have achieved that, I would not have achieved that, if we were not capable of understanding each other's strengths. For me what was great about you was, yes, I could give you a broad stroke as to what I wanted, and you could fit that within the overall vision of the show. And then as you rightly say, and as you've experienced yourself now as a DP, the DP can then focus on other things.

The higher you go up the ladder, the more you're an overseer of other people's work and the less physical work you do. But my goodness you are doing a lot of thinking, and people management. And I think the indication of good management is when the senior people seemingly have very little to do. So, on Magic City, I had more time to sit back and go to the D.I.T. area and look at the monitors there, more time to speak to the director and more time to speak to the actors. That was because I knew that you could be trusted absolutely, not only to realize the vision but to improve on it because you've got a great eye. You also have a great understanding of how to manage a crew. On Magic City there were a lot of electricians, and a best boy, and everyone else, plus equipment, and cables, and lighting orders to manage. I loved our crew, but I couldn't name every person who worked in the lighting department. But you probably could. And it goes to how complex the job of a cinematographer is.

There's so much going on in your departments, you can't micromanage, which is why you need great gaffers. And in fact, I was so impressed with the work you did on that show, I brought you to Canada to shoot my own film. It doesn’t seem logical that I would hire someone who I'd worked with as a gaffer to be a DP But, I feel I've been proven correct and that you were essentially a DP already because a DP has to have a profound understanding not only of the technical side of lighting, but its creative impact on the audience. That was a great thing about you. You understood the creative implications of every decision you made. The second reason you were a great person to hire was you have a great eye and a great visual understanding of composition. The third reason is that you're a great leader of people. I was a little nervous before you came to Canada because I had never worked with you as a DP and you're a soft-spoken man but, what was great is you came in and immediately you took command of that crew and they loved you and they followed you.

So, could you talk a little bit about when I first hired you to shoot Last Call, what your thoughts were and then when you arrived on location what your game plan was for managing that group, which by the way was a crew you had never worked with before.

Antal:

Well, let me start by saying when you called me, I thought you were just messing with me. Once I realized that you were serious, I was very excited but to be honest I was also extremely nervous. It felt like the opportunity of a lifetime for me to work with you, which I already knew was going to be a great experience and, to shoot a film in black and white with a great script and with an incredible cast of talented A-list actors.

My first and biggest hurdle was that we were shooting in Montreal and I had never shot in Montreal before, so I didn’t know any crew there. I already knew how you liked to work so I knew I would need to put together an ace crew. I needed to find the best camera operator available there. I interviewed about a dozen operators and finally found Robert Guertin. If I wouldn’t have found Robert and he hadn’t agreed to do it, I’m not sure what my experience on Last Call would have been like. Robert was not only a stunning operator but also a lovely human being with a very calm temperament. He was the perfect fit for us. His entire camera crew was great. Even though this was a relatively small indie film, they were all completely professional and a hundred percent dedicated.

Then next came my gaffer Daniel Dallaire who was a young guy. Even younger than me. We spoke and his English wasn't great, but I could tell he got it. He was very enthusiastic about the film and I knew that he was going to come in with a crew that respected him and that can be a tough thing to find on a low budget indie.

Somehow, across the board we were able to get really great crew who were all very professional, very talented and really gave it their all. You would never have known by our set what the budget was and most definitely not by the work that was taking place under very difficult conditions. On all films, especially low budget indies, there are always unexpected obstacles. About a week before principal photography, we lost our main location where most of the film was going to be shot. It was an old bar and restaurant, which was a perfect location for our main sets. Then, while the art department was working there, they found black mold in the walls which would have endangered the cast and crew. We ended up having to build the whole thing on a stage in very little time otherwise we would have lost our cast who had other commitments right after our film and the film would have died. It was pretty intense. We were constructing the set while we were hanging the grid. Every day the construction workers, the rigging electrics, everyone, was working together to get it done.

Rhys Ifans as author Dylan Thomas

Steven:

Yeah. That was a huge obstacle for us to overcome but luckily Sylvain Gingras, our production designer, was brilliant and built us some amazing sets in record time. But unfortunately, it was a big financial hit for us and I had to rewrite and cut some scenes.

So, tell me about the advantages of shooting on the stage for you in terms of lighting.

Antal:

Well, the advantage of shooting on the stage rather than the location in terms of the lighting was that everything could be controlled. So even though we didn't have a lot of time and we had to work hard to build a grid and rig all the lights, it was actually a blessing not to have to worry about what time of day we were shooting. The original location had windows which meant I would have had to control the light, day or night. On the set I could create whatever I needed.

Steven:

I'd love to talk to you about the first day we shot in a period train carriage, but it wasn't a train carriage at all. The art department built just that part of the train. It was very simple. A window, three walls and the seat. Our visual effects guys came up with the idea to put the “carriage” on large tractor trailer tires, so we were able to rock it in a way that was controlled and looked like the motion of a real moving train. We bounced a Xenon light in a mirror through a rotating spoke wheel to create the moving light we needed to sell the illusion of a train moving through a landscape in Wales at night. The Xenon is a very directional light so when you bounced it off the mirror you see the shapes moving across the faces very sharply, right?

Antal:

Yes. We did have to soften it up a little. We also had a bit of wind going outside the window and we sprayed some water on the window for the rain you wanted. You know when we're outside of the train looking in it just works beautifully. It looks completely real. You’d never know we were on a stage in a small twelve feet by twelve feet area.

Steven:

And of course, the bar, where most of the film takes place, was not a real bar. It was built and shot on a stage with a grid overhead. Tell me about how you treated the windows.

Antal:

You, Sylvain and I designed the bar set with a large window in the front, and that was my motivation to work off of as much as possible. It gave us beautiful back light, we had some great depth because we had a half of a street and a return on the other side of the window where we would have extras walking. So when we would look outside we would have movement, and it really sold it.

Steven:

So the outside and the inside were on the stage. But you lit that outside area differently, I guess, from the interior so it was brighter outside?

Antal:

Yes, it was lit a few stops brighter, so it felt real. And we had a 20K that we would soften sometimes depending on the mood of the scene. We would change its height or its angle depending on what was needed.

Now the one thing I do want to say is that the toughest thing that I found photography-wise, and this is something that I never could have thought of until actually doing it, was how challenging it was to shoot black and white.

Because of the budget, we didn't have the luxury of having a D.I.T.

Bernstein and Carolyn Rodney with John Malkovich on the set of Last Call

Steven:

Let me briefly explain for the people who aren't familiar what a D.I.T. is.

A D.I.T. is basically a digital technician. The image comes through the camera and the D.I.T. takes the digital information and can then adjust it, can modify it, can increase the density of the blacks, can make it low contrast, high contrast, etcetera. Normally independent films would hope to have a D.I.T. technician working with the cinematographer, but we couldn’t afford to do that.

Antal:

No. So I realized very quickly how subconsciously I use, and how we all use, color as separation. So when I was void of color I was having to tap into a place that was there, but it was difficult, it's almost difficult to describe. The textures, the depth were all built on contrast, different shades of contrast, and I found it very challenging. I really did.

Not being able to use cool light versus warm light to set the mood of a scene, and having to strictly do it with contrast was hard, but luckily, like I said, our production designer was great and our costume designer Molly Maginnis was amazing and it worked. They had a lot more experience than I did with black and white and the sets and wardrobe helped me a great deal.

Steven:

The wardrobe and the way the set was designed would help separate one object from another because of the colors they chose. Because when you're doing color photography, the color separates from a background, but when you're shooting black and white everything is shades of gray so for example, you have to have a light colored sweater with a dark background to help separate. So I guess separation was a challenge you were working with all the time. You used a lot of back light I seem to recall as well, didn't you?

Antal:

Yeah, we definitely used a lot of back light. For the most part a 20K with some bounce return and we always had one LED, the only LED we could afford, on stand-by just to fill a little, to catch the eyes, and we worked extremely fast. I don't think we had one hour of overtime on that entire film. We made our days every day. We couldn’t afford not to. We worked so fast, luckily I was able to fall back on my film background where I had to light by eye and light meter, because by the time I would go to look at the monitor, which wasn't calibrated, there was no time to walk back, we were going to shoot.

Sometimes in between takes I would silently make sure to make an adjustment that I don't think anyone ever noticed, but pretty much when we were ready to go that was it.

Part 2 coming soon...

About the author:

Steven Bernstein, DGA, ASC, WGA is an ASC outstanding achievement nominee for the TV series Magic City. He shot the Oscar winning film “Monster,” “Kicking and Screaming,” directed by Noah Baumbach, “White Chicks” and some 50 other features and television shows. The second film he wrote and directed, “Last Call,” stars John Malkovich, Rhys Ifans, Rodrigo Santoro, Zosia Mamet, Tony Hale, Romola Garai and Phil Ettinger, released late in 2020 in to theaters in selected cities.

Steven can be followed at Stevenbernsteindirectorwriter on instagram where he regularly posts short insights and illustrations about filmmaking.