07-10-2020 - Case Study

The Relationship Between the Director and the Cinematographer - Part 1 of a Series

By:

Steven Bernstein, DGA, ASC, WGA is an ASC outstanding achievement nominee for the TV series Magic City. He shot the Oscar winning film “Monster,” “Kicking and Screaming,” directed by Noah Baumbach, “White Chicks” and some 50 other features and television shows. The second film he wrote and directed, “Last Call,” stars John Malkovich, Rhys Ifans, Rodrigo Santoro, Zosia Mamet, Tony Hale, Romola Garai and Phil Ettinger, is scheduled for release later this year.

Steven can be followed at Stevenbernsteindirectorwriter on instagram where he regularly posts short insights and illustrations about filmmaking.

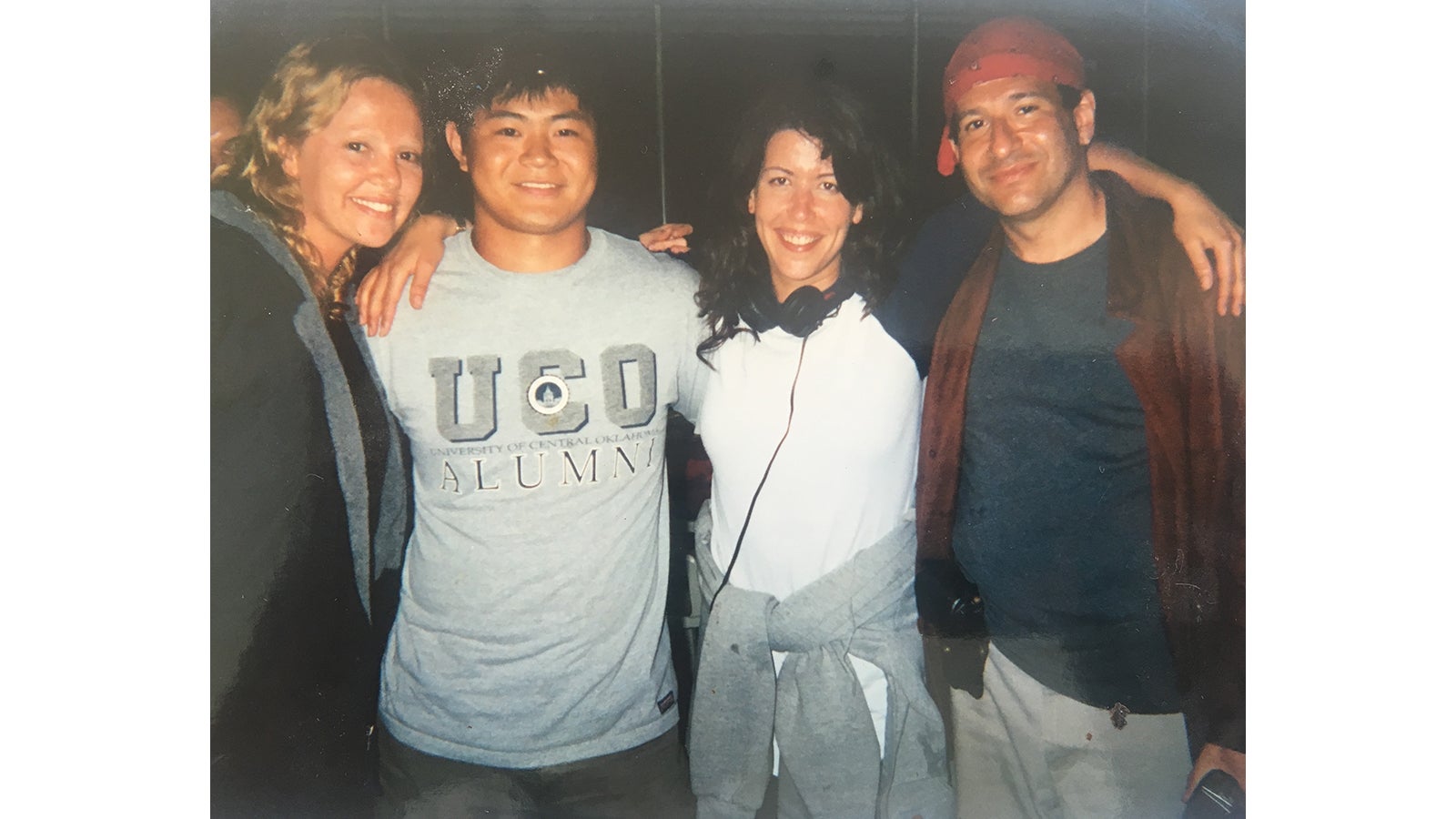

Bernstein, right, shooting "Monster" with Charlize Theron and Patty Jenkins

The relationship between the director and the cinematographer is central to the success of a film. I have had the rare privilege of being first a cinematographer for over thirty years and then a director of feature films. It has given me a unique perspective on both jobs and their connection. In all of art, this relationship between the director and the cinematographer is unique. Few artistic undertakings require the level of collaboration typical of this union; when it works, it makes for a better film. When it fails, it is a catastrophe.

The auteur theory suggests that directors are the authors of their films, and I think that is right. But it is authorship that comes as much from the management of other artists as it does from a singular vision. It is more useful to view the director's job as a unifying intelligence rather than a single creative font. The director is undoubtedly the final decision maker, and there are thousands of decisions to be made each day, but filmmaking is complicated, and the origins of good ideas come from many sources. The production designers, the actors, the writers, the editors, the costume designers, and more people than I can mention here, make profound and significant contributions to a film. Not all their ideas will be right or brilliant, and the director remains the ultimate arbiter of their value. Still, many times these support artist's notions will significantly impact what the audience ultimately experiences in the cinema. Among them, I would conjecture that one of the most significant contributors to this process is the cinematographer.

Photo Vasilis Pitoulis

HOW DIRECTORS AND CINEMATOGRAPHERS FIND EACH

Let's talk about the process of how a director hires a cinematographer.

The first thing, of course, is how the director becomes aware of the cinematographer's work. Maybe you have had a film in the theatres or on television that the director likes; and that is the ideal scenario. For a director and the director's producers to see a complete and successful film, offers a DP one of the best chances for employment, but it isn't a guarantee for a lot of reasons I will discuss. Still, it says to the director that their future collaborator has proven themselves in the trenches and will be a safe choice. But there are other things to consider.

Virtually every cinematographer will have a reel, but the reel must be seen by the director to get them employed. Getting the reel to the director is tough; directors are very busy from the minute they are funded, and they will want to take the most efficient route to find the right person to photograph their film. That efficient route won't be looking at hundreds of reels. Instead, they will look to reputable agents.

Agents

Agents are great things for cinematographers to have, first because they have a better chance of getting a cinematographer's work to a director. Further, if a director trusts an agent, it is an excellent way for the director to save time. The director can also ask the agent for particular types of cinematographers, which also saves time. For the cinematographer, the hope is the agent can promote them, so the cinematographer doesn't have to become a sales-person. No one believes a person when they promote themselves; it is more credible when someone else is doing it.

Most of the principal agencies have below-the-line departments, and this is where the cinematographer's agents reside. There are also standalone agencies that specialize in cinematographers.

The procedure for securing a DP for a director is straight-forward. Someone working for the studio or production will contact the agency (or several agencies). They will describe the project, sometimes based on a document produced by the director that represents their vision. They might mention the project's budget, whether it's a comedy or drama and all the other significant details. Right away, the agent will start thinking about DP's who have shot comedies for the comedy, and DP's who have shot drama for the dramas or action for the action.

So agents work as a bridge between the cinematographer and the director. It is important to note that agents will typically represent many cinematographers. They can't live off the income of a single client. So having an agent may get the cinematographer in the door, but it is a double-edged benefit. Cinematographers shouldn't be shocked when they find out that their agency sent another fifteen reels along with theirs. An agent rarely pushes an individual cinematographer. So the DP is going to have to get in the room and impress the director. The agent can help get them in the room, and if the meeting with the director goes well, the agent can help close the deal. An agent will also get the DP a better deal once a deal is to be done. So they are certainly worth it, but every DP should know that it will ultimately be down to them to impress the director. And that will begin with the showreel.

Directing Zosia Mamet, Rodrigo Santoro, John-Malkovich on "Last Call"

ABOUT THOSE SHOWREELS AND OTHER FACTORS

Directors will be looking for particular things from a showreel that a cinematographer has to be sure to include. To anticipate what a director wants to see, a cinematographer must understand what makes them valuable for a director and also the pressures and influences to which the director is subject.

If the director works for a studio or a major production company, they will probably not be the only decision-maker in selecting a cinematographer. I was up for a big film once with a director who wanted me for the job. We talked, we agreed, and everything seemed set to go. But the studio was nervous as it was the director's first major film. They wanted someone who they had worked with before and would be directly answerable to them. They loved my reel, they liked me, but we didn't have a history. I didn't get that job. There is nothing that my showreel could have had that would have made a difference.

The cinematographer never fully knows what determines their hire, and it certainly isn't only their reel, at least not directly. But a reel can send some critical messages beyond the craft and beauty of the cinematographer's work. To better understand, consider a few things.

Studio-think. To understand getting hired by a studio, you have to understand studio-think. Studio-think means that it's not succeeding that's on everyone's mind; instead, it's not failing. To understand studios and those executives to whom the director answers, know that they are risk-averse. Let me tell you why. If the director wants an inexperienced cinematographer and a junior studio executive sanctions the hire, they are taking a considerable risk. If, in the first few days of shooting, the shoot falls two days behind or the DP argues with everyone, or is disrespectful to the actors, or turns out to have a drug habit, the junior-executive may lose their job. So might the director, or at least their judgment is going to be questioned from that day forward. The defense, that the DP had a pretty reel, won't count for much. The DP didn't have a track record with the studio, they were inexperienced and failed. End of story.

Now, let's consider the same nightmarish situation, but this time, the director selected an established DP. Of course, the DP will still be fired, but the junior-executive and the director can say to their bosses, "look at this long resume; who wouldn't have hired this guy?" Or "the studio used them before." They are off the hook. They haven't succeeded, but more importantly, (for them) they haven't failed. They haven't found the next great DP, but they haven't sacrificed themselves or their careers. Self-preservation pervades the entire industry. This makes it difficult for people starting out. They can't, after all, alter the amount of experience they have by altering their showreel. But there is something they can do, and that is to emphasize those things that will be coveted by cautious directors.

Directing Rhys Ifans

On bigger films, a cinematographer is going to be working with known actors. That's why some think it is important to open a reel with beauty shots of known actors. These actors are also considered "brands," which means their recognition gives them value in the market place. Many of these actors and actresses are valued not only for their ability but for their appearance. Their good looks are part of their "brand" and they, and the people who will be working with them, including the director, will want to protect it. Usually. On the Oscar-winning film “Monster”, I was employed to make one of the most beautiful women in the world, Charlize Theron, look terrible. It was a success. She looked awful, and I became better known as a result and was hired on other films. “Monster” went on my reel. When you shoot an Oscar-winning film, it goes on your reel. But I made sure to sequence it after the beauty shots. Because a cinematographer is trying to demonstrate at least two things on their reel; that they can shoot beauty but also that they are comfortable working with well-known actors. This latter point is an important one. The cinematographer will spend a lot of time with the actors and will critically influence an actor's appearance for every single second they are on screen. The director needs to know the actors are in safe hands and a DP showing that they have done good work with major stars before, is a good way to provide that assurance.

It must seem odd that if it's not on a DP's reel, a director won't believe the DP can do it. But many directors are concerned that in a culture where everyone is selling, the cinematographer could be overselling their skills. Directors want evidence. As crazy as it sounds, comedy on the reel has a better chance of getting a DP comedy, action, action, drama, drama and a film that is going to have a lot of effects and green-screen, is probably going to be shot by a DP who has a lot of green-screen and visual effects on their reel. It's all fear-based, but it's the nature of this world.

Another note about the reel. A big film is a high-pressure environment that requires a strong character and considerable management abilities. If a cinematographer cracks under the strain, the whole edifice can come down. On the other hand, on low budget independent films, a DP will have to work with limited resources and on a much shorter schedule, an entirely different sort of pressure. In both cases, directors will not only want to see specific shots and abilities demonstrated on a DP's reel, they will want to see their type of film. They need to know a DP can thrive in their specific environment.

Young DPs won't always have everything on their reel they need to be in the running for every job. Better they only include what they do have and not try to cut in material from commercials, videos or student shorts. Speaking as a director, I can tell you that one amateurish shot undoes the impression created by twenty great shots. Reels can't be faked. A director will look at a lot of reels when searching for a DP and is short of time, so they will be ruthless. They have to be. They will quickly identify shots that are “filler" and the reel will be tossed aside. So the lesson is that less is more. A few perfect shots, or a perfect sequence, might be just enough to get the DP the interview, and that's really the only object of the reel.

For all the same reasons, directors under enormous time pressure don't have time to look at slick, trendy graphics and complex content maps. They just want to know quickly whether a DP interests them and whether they want to have a meeting with that DP. So short, good reels with high quality work are the most effective.

Please stay tuned for Part 2 of this series, which will post very soon.