01-03-2022 - Case Study

The Camera Operator / DP Relationship – Part 2 – Collaboration and Poetry

By:

This is a continuation of the conversation in Part 1 of this article – The Camera Operator / DP Relationship – Part 1 – Communication and Going Again

Michael Ferris, SOC, in gloves, on set with actor Maggie Grace. All photos Jeff Berlin

Steven Bernstein:

Let’s talk about how shots are blocked and prepared. During the blocking rehearsal, is the camera operator there with the finder? Does the DP say where the camera is going? Do you work with the DP on determining where the camera's going to go?

Michael Ferris:

Well, in my view, there can be a lot of variations on that. However, my experience is it's primarily assistants who are trailing the DP wherever they go, so when they want to be dead accurate, they just turn, and the finder is in their hand. Sometimes because you have the authority or feel a kinship with a DP, you'll take the finder and do that job. When it's a good relationship, it's an intimate relationship between the DP and the operator.

Steven Bernstein:

Well, the DP will take the finder, walk through the rehearsal, say to the assistant, "Put a mark here, put a mark there," so then as an operator, you can see where the marks are, what the lenses are, and the DP will in general, say, "This is what the shot is going to be, here's the frame and here's the blocking rehearsal we've prepared. This is where the actors are going to go." At that point, the operator gets more involved and then starts working with a dolly grip and so on. If you see something that isn't working or could work better, how do you communicate that to the DP?

Michael Ferris:

Well, it depends on the level of seriousness. If it's a small problem and you have a good relationship with the DP and know that they won’t take offense, you can adapt. However, you're not moving actors; you're not moving furniture; you're not doing anything serious. You want to do the things which make their life easier because they're small. If you see something from your own experience that they can use, go whisper it in their ear, or you tell them outright. It all depends on your relationship with them. Also, the dolly grip is a very, very important member of the crew, especially for the operator.

Steven Bernstein:

Let's say you've got a tracking shot. What are the options available to how that camera can be mounted? Does a DP make that decision? Do you?

Michael Ferris:

Easy answer. The DP makes that decision. They could add dance floor, which is basically plywood with a cover on it that's laid on the floor.

Steven Bernstein:

It allows the dolly to move in any direction so you can make small adjustments, right?

Michael Ferris:

Correct. For me, the poetry for an operator comes in seeing that door and preplanning that frame. You must have all that worked out. When they come through, do they stop? Do they go right or left? Whatever they do, you have to be in total uniformity with them, which is why the grip is so important to the operator. I always wanted the dolly grip to be there with me because they're moving the whole machine. I can adapt their movement to a degree, but I preferred them to have their say about the movement.

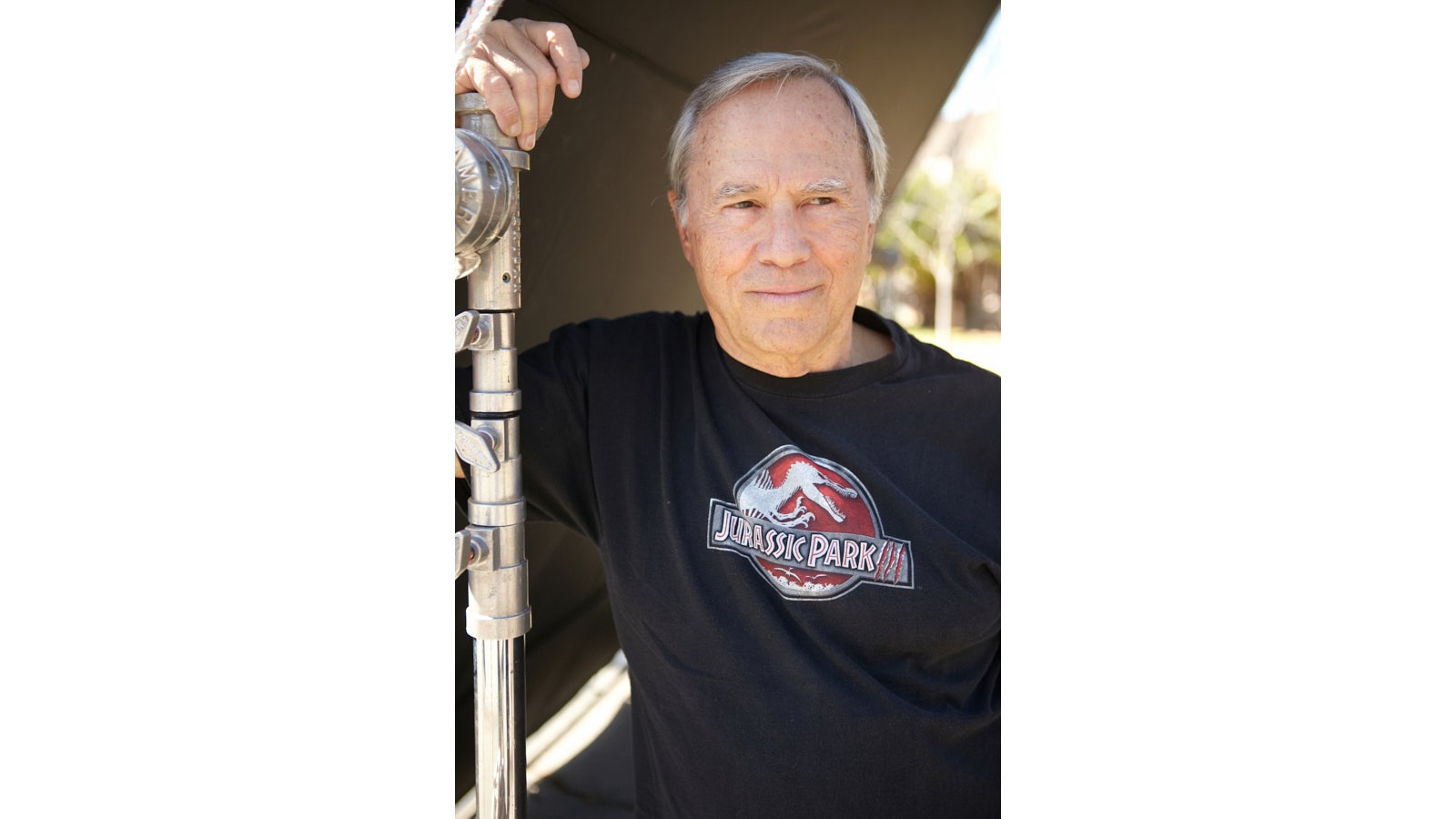

Ferris on set with the author

Steven Bernstein:

So, part of your creative process is collaboration. You collaborate with the dolly grip, who will understand the general direction and composition you or the DP have instructed. But where a person is in a frame is a big part of your job. Can you describe that to me a bit?

Michael Ferris:

Well, composing a shot is a matter of taste, and everybody's taste is different. One of the things that's high pressure for an operator is if they don't have the same taste as a DP. It doesn't work if they're not happy with a camera operator. My first responsibility is to get the vision which the director and DP have assigned to the crew and me. It's essential to reproduce that, but I'll reproduce it the way I think it should look until someone tells me different. Also, to your previous point about collaboration, I want to make a point about assistants because sometimes when you change a focus from background to foreground or vice versa, you have to do that quickly or slowly in a very subtle way. It's very important because it's a key physicality in making films. The eye will follow wherever the focus tells you to go. So, assistants are very serious in that creative moment.

Steven Bernstein:

Going to the idea of compositions. There'll be a discussion between the DP and camera operator about what's in the frame and what isn't. One thing I think is very important that you haven't mentioned is how you report back to cinematographers, what you are seeing because sometimes I'd use very low light. You can't always see that on the monitor, but you could through the viewfinder. How do you feel creatively about viewfinders vs. monitors?

Michael Ferris:

Operators live and die by what you can see. When you're looking at a dark scene, the DP, director, and operator will talk about, "Okay, let's do it this way instead of the normal way, because we want to affect this feeling, or we want to see this instead of that." If I'm left to my own, I'll go where my instincts take me. But if you're looking at a dark scene, well, I may communicate to a DP simply what I see that I don't think he can see. This is again about the sensitivity, taste, and relationship between an operator and a DP. When you reach a certain level in your skillset, you have to work with DPs you've never worked with before. But the ideal is for the same crew to work with the same DP repeatedly because you know each other, you like each other, you trust each other. And when you have that mutual respect and trust, you can do anything. If I can come to you and say, "Boy, did I screw up?" You're not looking to hang me up by my heels. You want to fix it.

Steven Bernstein:

So important. Something else an operator often does is look through your finder and determine whether the eye line looks right. What do we mean by looks right?

Michael Ferris:

The only way you can become confident with that is through experience. It takes a lot of looking through a lens and doing the job and learning from people who know how to do it. There's only one way to get the eye line correct, and it's easy, except it's hard. How many movies not only have continuity mismatches, but they don't have eye lines right. That's another collaborative aspect. For instance, if you're doing a dining room scene with ten people, I get as confused as anybody, and I remember coming to you to say, "Steve, we got this right?" Because it is very complicated, complex, and very technical.

Ferris lining up a shot with actor Maggie Grace

Steven Bernstein:

Now you've worked with me a lot, and I use a lot of cameras. So, there'll be several operators and specialists like Steadicam operators and crane operators. As the senior or principal operator, how do you work with the other operators to make sure all those shots can be cut together?

Michael Ferris:

I talk to them and the DP a lot. The idea is that not every camera is getting the entire action. I may be getting the master, while other cameras will get little details. Each camera will have a different function. You need to know what the other cameras are getting to know what you don't have to get. When using multiple cameras, the operators must know what the other operators are doing.

Steven Bernstein:

Yeah, and in fact, everything you've talked about today is around the theme of collaboration, which is why you are such an important figure. When you worked with young DPs, you've imparted your considerable knowledge, not only based on contemporary film practices but also on the historic and important films you've worked on in the past. It is hugely impactful when you can inform a shot based on your experiences with Brian De Palma. I should mention you worked with Orson Welles. Then, of course, your work with John Cassavetes. How was it different working on a John Cassavetes' film?

Michael Ferris:

Oh, well, night and day. John Cassavetes didn't care a hoot about anything technical. He didn't care about focus. He wanted his characters in the frame, but he evolved his own kind of technical visual language. When the shots on A Woman Under the Influence are out of focus, somehow, it worked for the scene. Because the scenes could be rough and hard, we had no marks. We didn't know where they were going, we had to fake that, and we did pretty well. He made a camera operator out of me because he knew how badly I wanted to be in the camera department.

Steven Bernstein:

The thing I think is super important is some films can be rough and ready that are mainly about performance. Their imperfection is almost part of their virtue in that you just shoot, and you gather information, and you find art, but it doesn't have to be technically perfect. Then there are other shoots, with all the equipment in the world, where everything must be technically perfect. Both are films, both are valid, just different methods, and both work.

Michael Ferris:

Exactly right. John was after feeling emotion, and he couldn't get it by putting down marks.

Steven Bernstein:

He would speed the process up to eliminate those obstacles to find the truth of the characters.

Michael Ferris:

That's right.

Steven Bernstein:

That's very interesting. Now, modern equipment has changed considerably. We're currently shooting with digital cameras like the Sony VENICE, for example. Thoughts on that?

Michael Ferris:

Well, digital cameras are better for a lot of obvious reasons. They're very efficient. They have managed to make digital look more and more like film, which I personally like, but also, they're less expensive. They're easy to deal with. I don't know what they're like in the desert. I do know underwater they're much faster. You don't have to reload. You don't have to come up for lens changes. There's a small zoom. Things like that have made an enormous difference. The only negative, to me, is no more optical finders. That's the issue for me. Otherwise, they're great.

Ferris after wrapping a scene with actor Alice Eve

Steven Bernstein:

One of the great things I find, with Sony, in particular, is they've got this fantasy camera, but there's a version of it called the Rialto, which gets very small. The camera's size is significant because when you're shooting, it becomes an obstacle to fluid movements if it takes up a lot of space. Now you've got cameras as small as an iPad, and you're shooting 4K or 6K, and it's outstanding quality. Talk to me more about underwater work and your relationship with DPs and directors underwater. How do you communicate? How do you get shots?

Michael Ferris:

Well, a monitor is very important for that. You learn to come to the surface a lot and talk. You do what you do on a set, except when you go down, you have to have an idea of the shot. You make diagrams, work it out in pieces, shot by shot, and if there are any questions, you get them worked out before you go underwater.

Steven Bernstein:

You were shooting with a camera underwater on Never Say Never Again, is that right?

Michael Ferris:

Yes, it was a sequence that took three months. So, this was real filmmaking, but communicating doesn't change. Underwater, the people surrounding the director were the best in the world. People he'd worked with for thirty years, and they all spoke a language underwater. They could make signs. You knew exactly what was going on. So again, experience is very important.

Steven Bernstein:

Do you have radio communications underwater with the DP, or do you come up to the surface all the time?

Michael Ferris:

We have had them, but they usually last a day or two before you get rid of them. They're just in the way.

Steven Bernstein:

Then the DP has to light underwater as you're photographing.

Michael Ferris:

For a long time, DPs didn't, but then I worked with Bob Steadman. He was very creative, and he lit underwater. That's one of the reasons we got the job to work on Raise the Titanic, which was six months in Malta, because we had to light everything, and this is 2,500 feet underwater. It's a lot of time. Communication is everything.

Steven Bernstein:

That's why underwater is so difficult. People push very hard to go faster, but things go slower underwater, and communicating with the DP and director becomes difficult. When there's a technical problem underwater, it's exacerbated, and people get exhausted. To quickly summarize what we're drawing on, can you, as best as you can, list the ten biggest films that you've worked on?

Michael Ferris:

Where's my resume? At the time, Water World was the biggest film ever made. $219 million was an incredible amount of money. Scarface.

Steven Bernstein:

Blue Thunder.

Michael Ferris:

Blue Thunder, very big.

Steven Bernstein:

Never Say Never Again?

Michael Ferris:

Keep helping me.

Steven Bernstein:

Die Hard?

Michael Ferris:

Die Hard. Rambo 3 was five months, and it was massive.

Steven Bernstein:

Tell us a few of the John Cassavetes films you worked on.

Michael Ferris:

I worked on A Woman Under the Influence, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie.

Steven Bernstein:

Masterpieces. You've worked with Orson Welles, one of the most important film directors of the 20th century. John Cassavetes, arguably one of the most important film directors of the 20th century. Brian De Palma. That's quite a career, Michael. Thank you so much.

Michael Ferris:

Great chatting, thank you.

About the author:

Director / DP Steven Bernstein, DGA, ASC, WGA is an ASC outstanding achievement nominee for the TV series “Magic City.” He shot the Oscar winning film “Monster,” “Kicking and Screaming,” directed by Noah Baumbach, “White Chicks” and some 50 other features and television shows. The second film he wrote and directed, “Last Call,” stars John Malkovich, Rhys Ifans, Rodrigo Santoro, Zosia Mamet, Tony Hale, Romola Garai and Phil Ettinger, released late in 2020 sinto theaters in selected cities. "Last Call" is now streaming on Amazon Prime.

Steven can be followed at Stevenbernsteindirectorwriter on Instagram where he regularly posts short insights and illustrations about filmmaking.