07-31-2020 - Case Study

The Relationship Between the Director and the Cinematographer - Part 4 of a Series -- On Set Leadership

By:

Follow this link to read Part 1 - The Relationship Between the Director and the Cinematographer - Part 1 of a Series

Follow this link to read Part 2 - The Relationship Between the Director and the Cinematographer - Part 2 of a Series

Follow this link to read Part 3 - The Relationship Between the Director and the Cinematographer - Part 3 of a Series

Author Steven Bernstein, DGA, ASC, WGA is an ASC outstanding achievement nominee for the TV series Magic City. He shot the Oscar winning film “Monster,” “Kicking and Screaming,” directed by Noah Baumbach, “White Chicks” and some 50 other features and television shows. The second film he wrote and directed, “Last Call,” stars John Malkovich, Rhys Ifans, Rodrigo Santoro, Zosia Mamet, Tony Hale, Romola Garai and Phil Ettinger, is scheduled for release later this year.

Steven can be followed at Stevenbernsteindirectorwriter on instagram where he regularly posts short insights and illustrations about filmmaking.

Evaluating the mise en scène with Romola Garai on the set of Last Call

Storyboarding

There is much discussion between directors and producers about whether films should be storyboarded. Perhaps it’s another way of thinking about visual language. It's also a way for the director and the cinematographer to make sure they have the same understanding of their approach to a sequence, and that is easy when it is illustrated.

I certainly advocate storyboarding complex action-sequences. These sequences employ several cameras. Also, some elements will be shot at different times and in different places and incorporate things like visual effects, miniatures, etc. That is a lot to coordinate and a storyboard is the only way to keep it all straight. But for ordinary sequences, I am not sure storyboards are always a good idea. I'm a great advocate of planning, but also of creative spontaneity, which is to say, I have to be open to changes on set, particularly once the actors get involved. To go on to a set and tell the actors where they should go based on your storyboard and not their own intuitions may prevent the actors from providing a good performance. So this is just a word of caution. Preproduction meetings between the DP and the director are about creating a visual narrative, which is important, but one should still be open to the evolution of ideas that invariably happens once everyone is on set. The good news is that extensive planning actually facilitates spontaneity on set. A director can take risks if they know they have a detailed fall-back plan. Ultimately the best solution is a hybrid, of detailed visual planning, and the incorporation of what the actors and the director feel is right on the day. The DP will have the visuals worked out, but also the ability to alter the plan.

It is great if the DP got several meetings with the director. But as preproduction goes on the director will be pulled away from the meetings with the cinematographer and the cinematographer will still want to make good use of their time. One way to do that is to have meetings with the other department heads.

As I said before, the director is the unifying intelligence and provides the overall vision of the film, but not the exclusive vision. The cinematographer (hopefully) because of the early meetings with the director will have a good idea of the director's intention. The DP can share that vision. Key people to share it with include the production designer, the costume designer, the assistant director, the production manager and the location manager. In the sequence, I have been using as my example; the DP knows that the director wants a cliff on a desolate landscape. The DP also knows that they will be using principally blue light and that the camera will be moving. This is essential information for the location manager and also vitally important to the costume designer, the production designer, and the production manager who, along with the assistant director, will have to coordinate all of these departments. If the director is the only source of all information, the demands on that director's time will be unreasonable. By having a senior collaborator who fully understands the director's vision and intention, the dissemination of information becomes that much more efficient. That is not to say the director won't speak to their other department heads; they most certainly will, but the DP can be of great assistance in the coordinating of the creative visual elements.

One of the key meetings between the cinematographer and the other departments is called a color meeting. Color is a big part of cinematography but also production design and costume design. If colors clash unintentionally or run against the emotional intention of the scene, then the film has been damaged. The cinematographer can often initiate the color meeting, or if the director has the time available, they can be included. Collectively, a color plan can be devised for each sequence. Once again, books from painters and clips are useful references as a shorthand for other artists.

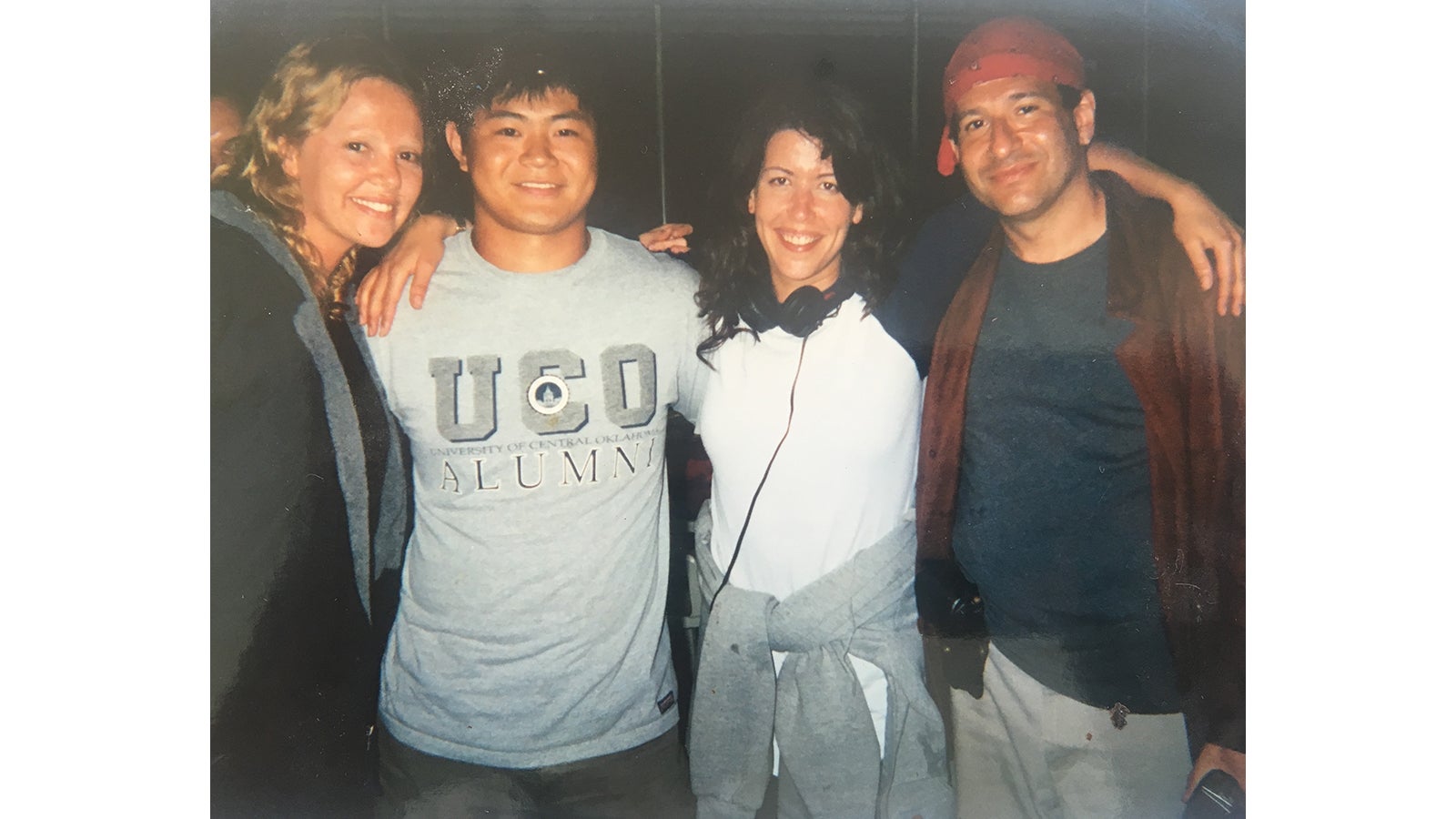

With Patty Jenkins and Charlize Theron shooting Monster

Leadership

All the complex interactions involved with the hundreds of people needed to make a film require good leadership, a virtue both a director and a cinematographer must possess. It's worth examining the fundamentals of leadership because if either fails in this regard, the film can lose its direction.

1. Admission of limitations. There are a lot of things about leadership that are counterintuitive. One of these things is the admission of fault and the acknowledgment of personal limitations. Years ago when I was a cinematographer I was surprised when a known director brought the whole crew together on the first day of photography. He announced that whereas he was excited to begin the film, he was very aware of his inadequacies, particularly on the technical side, and would be looking to the crew to help him correct him when he erred. You would think this humility would diminish him, but to the contrary, it made the crew see him as both human and honest, and it made them want to help. I've adopted this approach, and as a director, the first thing I do is tell the crew honestly not only my limitations but my fears and concerns. I do this each day of the shoot so the crew is fully aware of what challenges lay ahead and my own individual perspective on those challenges. I also did this as a DP. I wanted to inspire the crew, so I shared with them what I knew. This facilitates the crew by respecting them enough to give them the same information you possess. There's a temptation in all walks of life but particularly in the film industry to jealously hold onto information because unique information is a way to self-empowerment. But it doesn't inspire others, and as a leader, you have to inspire.

2. Sharing the vision. A companion action to the admission of limitations is the sharing of a specific and overall vision. As a director and as a DP I would tell the crew the creative vision for the day. If the crew knows what the director hopes to do and how the cinematographer means to help them achieve that, the crew will not be working in a vacuum. Instead, they will know and understand the specific objectives and focus on achieving those objectives. And I must tell you, they do.

3. Accepting blame. A rule for directors and cinematographers; when you do something wrong, admit it. It may seem counterintuitive, but crews follow people who exhibit integrity, and the admission of error or bad behaviour is the ultimate exhibition of integrity. Nothing is more demoralizing for a crew than seeing a director, who is all-powerful in many respects, pretending to be infallible while failing. The same principle applies to the DP. Hopefully, the DP and the director might have the sort of relationship that they can whisper to each other when one or the other is losing the crew. Certainly, that is the sort of relationship they should have.

4. Apologizing when wrong. Another counterintuitive part of leadership. This sounds like the same as accepting blame, but it isn't. Every good apology should have four parts. An apology not only acknowledges fault (1), it also recognizes that someone else has been injured (2). The person who did the injuring should express their regret and explain their real understanding of what they did wrong (3). Finally, they should explain what they have learned and how their behaviour will be different in the future. Saying instead that they are the director/DP and don't have to apologize to anyone, or that they are right, always, isn't going to get the crew to do their best work. In fact, few things are as frustrating as not getting an apology when you deserve one. It will alienate the crew. If that sounds complicated, well, leadership is complicated but also incredibly simple. Leaders who accept blame and then apologize in this fashion, command those they lead and earn their respect.

There is a rule all directors learn; they can never lie to an actor, even to praise a performance, because once the actor hears one lie, they will presume other things the director says are also lies. Better to give an honest appraisal of a failed performance than to compromise the entire relationship by lavishing dishonest praise on the actor. Actors want the truth, and so does the crew. The crew knows when a director or cinematographer does something wrong. They are at the center of the action, so no amount of happy-talk or spin will alter their perception. Leaders should inspire with honesty. Crews will work faster and better when you do.

5. Acknowledging the work of others. This is also part of leadership for the director and cinematographer. It is far better to give someone else credit then to self-aggrandize. Crews are aware that they are often working with famous people and feel their work goes unrecognized. People love to be valued and recognition and thanks inspires them.

5. Don't criticize. Neither a director nor DP should ever publicly, or worse, secretly criticize anyone. Certainly, a frustrated DP ridiculing or complaining about the director to other crewmembers completely undermines the crew morale. It also means the crew will not trust that DP again, because if they are willing to criticize the director behind their back, it is presumed they could well be criticizing crew behind their backs as well.

These may be strange principles to put forward in an article about the relationship between the director and a DP, but they are the single most important paragraphs. Most technical challenges can be overcome, and most practical and financial concerns can find a solution, but if either the director or DP lacks character and leadership or if they subvert each other, there is probably no recovery.

Bernstein directing Helen Hunt on the set of Decoding Annie Parker

Conflict resolution

It is impossible to get along all the time and particularly on a film set where everyone is in close proximity for long hours and under a great deal of pressure. Also, people will have their own creative visions. There are a great many artists working together, so this is inevitable. To simply presume there will be no conflict is not wise, and a strategy should be in place for the resolution of these conflicts. Particular those conflicts between the director and the cinematographer. Here are the rules as I see them.

1. Bite your tongue. There will be a lot of adrenaline-pumping once the shooting begins. All the emotional hair triggers will be primed and ready both on a big-budget film with a large crew or a small film on a tight budget. Things will be said. Rarely is it necessary to respond immediately to a slight or an insult, particularly one coming from a director and directed at the DP. We all have our pride, and no one likes to be publicly humiliated, but it is part of good professional practice not to let an argument escalate. You will be surprised to know that directors usually regret things they say in anger, but they are under such enormous pressure and are having to engage with so many people all the time, that it is inevitable something slips out. A good cinematographer and any good professional lets it pass, but if it is particularly egregious and no apology is forthcoming, there is a procedure for its resolution. Quietly and without anyone knowing, the aggrieved party can ask the person who made the remark to go off set with them and discuss the matter privately. This request shouldn't be a dramatic and passive-aggressive thing and said in a loud voice as that will only further escalate the problem. But so much of what happens on set between the director and the cinematographer is observed by many, and sometimes hundreds of people. Anything that happens between them impacts the entire film. So at the right moment, they can and should talk privately. It is the first step towards fixing the issue. I would add that some circumstances go beyond any reasonable behaviour. Directors can be passionate and even mistaken, but they can never be abusive, particularly with matters of race, religion, and sexual orientation. If the remarks descend to this, it is a matter for the producers and the studio and should be taken to them. But in my experience, the issues with directors and DPs and flare-ups of anger are usually about creative frustrations.

Once the private discussion begins, all matters can easily be fixed by using a relatively simple methodology. First, both parties have to acknowledge the other party's perspective and even try to state it themselves in a reasonable manner. Then they should state their grievance, but they should make it specific to the incident, and never, absolutely never, make it ad hominem, (about the person). The parties are trying to find a way to work together not change the other person's essential character. Never use words like "never" and "always" in describing a person's behaviour, and never bring up other related incidents. Always make the discussion specific to the matter at hand. The reason you should never say things like "always," i.e. "you always talk over me," or "you always do the opposite of what I suggest" etc., is there is no real reasonable way to address "always." The other party can't go over every single incident in a complex relationship. If the discussion goes this way, it is only going to exacerbate the tension.

On the other hand, if the DP says they were offended because "the director snapped at them," and the DP "understands that they are under a lot of pressure" and they "probably didn't mean it" but the DP's feelings were hurt, and they felt "diminished in front of the crew," it is surprising how positive is usually the response. If additionally, the DP or aggrieved party also makes a point of acknowledging how they might've contributed to the situation, then their relationship will only be strengthened.

Again this must seem a strange thing to talk about in an article about cinematographers and directors, but it's conflicts and arguments that do more damage to a film than virtually any other thing.

Leadership then is the ability to apologize for bad behaviour, to say in detail what you did wrong, outline what you would do differently in the future, and acknowledge the hurt you created in another. It means that an apology can be a positive force for the realization of the film's vision, as odd as that may seem. Leadership is also admitting your weaknesses, recognizing the work of others, and setting out a clear creative vision for all involved to understand and share.